The hospital that treated Kevin Campbell during his final months has been absolved of any blame in relation to his death despite acknowledging a “missed opportunity” to diagnose his condition earlier.

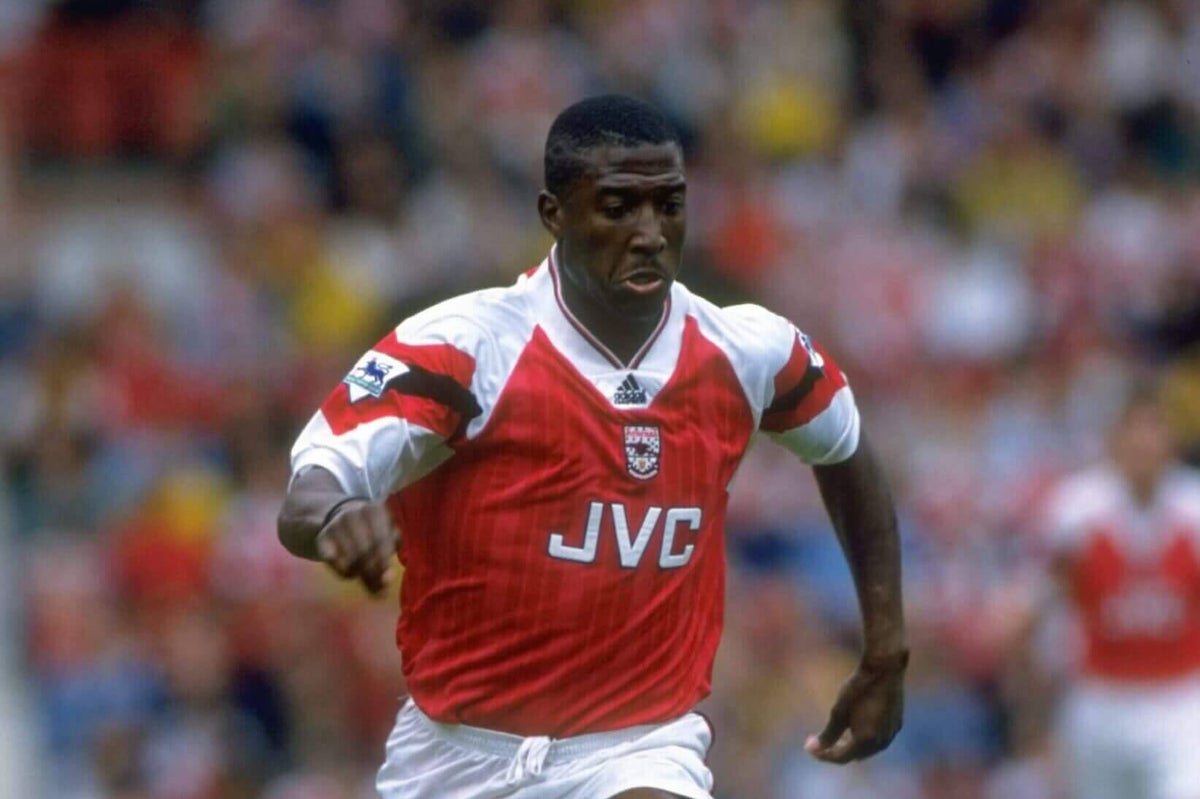

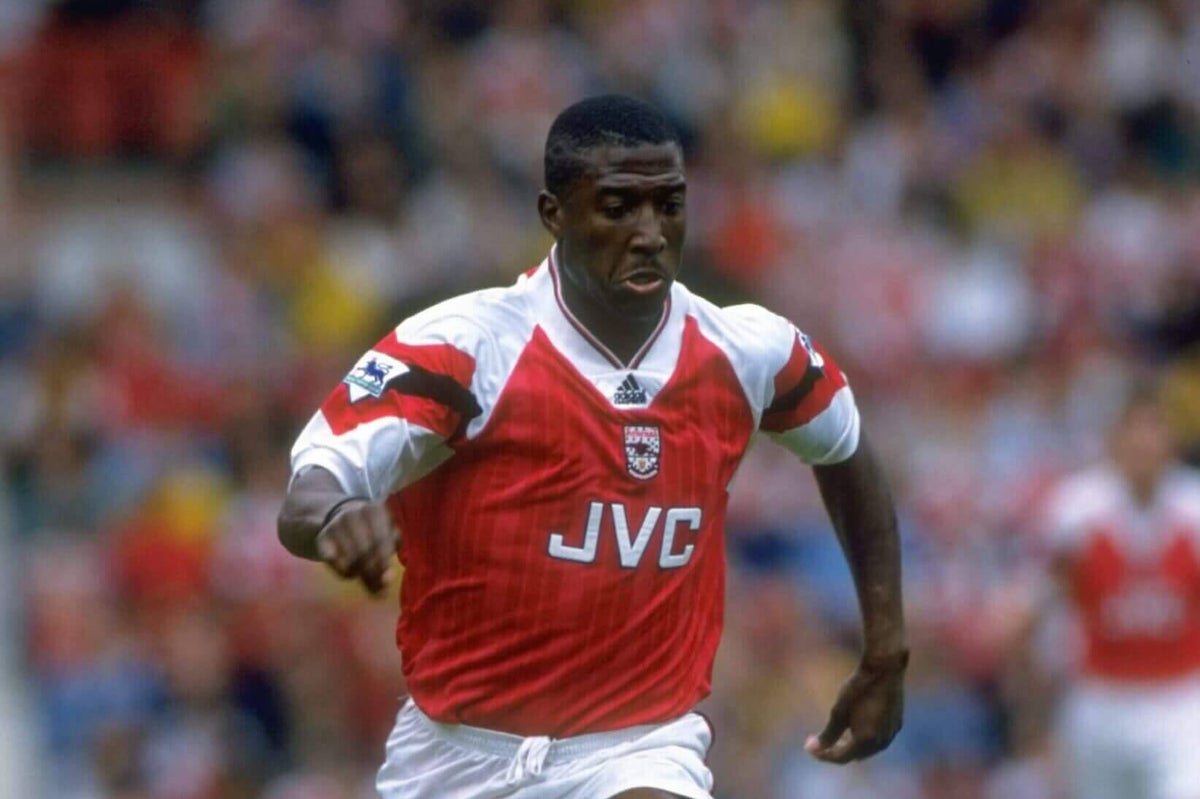

Campbell – winner of a league championship, FA Cup, League Cup and European Cup Winners’ Cup during his early years at Arsenal – died from multi-organ failure on June 15 last year, aged 54, after being admitted to Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) for the second time that year.

Advertisement

His case led to Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, which manages the hospital, declaring a Level 5 patient-safety incident – the most serious category – to establish whether his death might have been avoidable with an earlier diagnosis of infective endocarditis, a rare infection in the valves or lining of the heart.

However, an inquest at Manchester coroner’s court on Monday was told that the hospital had downgraded that to a Level 2 report after an internal investigation had concluded that an earlier diagnosis would not have saved the former footballer.

“Kevin was so weak as a result of heart and kidney failure and weight loss that even if we had diagnosed the endocarditis on that day (of admission) I don’t think his treatment would have been any different,” Robert Henney, a consultant physician for the MRI, told the inquest. “What he actually needed was surgery … but he was so weak that was not an option. Unfortunately there was nothing else that could have been done.”

The inquest was told that Campbell had not just been an elite footballer, widely known as ‘Super Kev’, but that he also had a societal impact as the first black footballer to captain Everton.

Campbell had also played for Nottingham Forest, West Bromwich Albion, Cardiff City and Turkish club Trabzonspor, scoring 148 career goals. He was, in the words of coroner Zak Golombek, “someone I remember watching growing up … it’s been clear from the outpouring of love from fans and everyone else connected to the game he meant a lot to many people”.

Campbell, who grew up in London but lived in Manchester during his final years, was admitted to hospital on January 23 last year when tests revealed “multiple abnormalities” involving heart issues that had led to chronic kidney disease as well as liver damage and caused him to have a stroke.

Advertisement

He was discharged on March 8 after six weeks of dialysis, antibiotics and other treatment but his condition deteriorated again after being sent home, leading to gangrene in his toes, and he weighed only 59kg (9.3 stone) when he was readmitted on May 17.

The inquest was told that Campbell had weighed 124kg (19.5 stone) before his first hospital admission. That had come down to 90kg (14.2 stone) when he was allowed to go home. He had lost more than ten stones in weight in under four months and Henney told the hearing “the weight loss was not recognised (by hospital staff) as early as it should have been”.

That, he said, was “something we acknowledge, and something we should look into, because it may have caused questions about why the weight loss had happened and that may have triggered other investigations.”

Campbell was so weak when he was re-admitted to hospital that, within five days, he was put on palliative care and his family – including his son, Tyrese, a striker for Sheffield United – were told he was not expected to survive.

A fortnight later, however, there was still an element of doubt among senior personnel at the MRI about what had led to his condition and how serious it was.

“He was active, alert, conscious and talked to me a bit,” said Henney, recalling seeing him for the first time on June 4. “It wasn’t what I was expecting. It was clear to me he was very weak. But it was enough for me to ask the question whether he was dying or not. It raised questions for me about whether we were doing the right thing. Occasionally you think someone is going to die and they don’t.”

Further tests revealed the seriousness of Campbell’s condition. Henney, however, said he remained troubled by the speed of Campbell’s deterioration. “The expectation (when he was discharged) was that he would continue to rehabilitate and get stronger. That didn’t happen and I didn’t really understand what had happened.”

Advertisement

Professor Peter Selby, the MRI’s associate medical director, also gave evidence to the inquest and said the hospital had to learn from the events leading to Campbell’s death, specifically in relation to tracking weight changes.

“Why was it that a man who a few months before was a picture of health had so suddenly deteriorated? One of our conclusions was that perhaps there should have been a little more curiosity about why that was the case.”

Ultimately, though, the hospital’s investigation concluded there was nothing that could have been done to save a man whose post-football career involving working as a television pundit. “My feeling was that there had been two completely separate and unrelated insults to his heart in a short space of time,” said Henney, adding that Campbell was “desperately unlucky.”

An earlier hearing had been told that Campbell’s family had questions about his “delayed diagnosis” and why he was not given an echocardiogram – an ultrasound heart scan – during his first hospital admission.

The family’s lawyers had also requested, unsuccessfully, that the inquest should consider independent reports to avoid a scenario in which it could be argued the trust were “marking their own homework”.

At the latest hearing, however, Campbell’s brother, Harold, and sister, Lorna, said via video-link they were “happy” with the coroner’s verdict that their sibling had died from natural causes. “From a family’s point of view, he was a superstar,” said Harold. “He was very loved.”

In reaching his verdict, the coroner said there had been “clear evidence of a missed opportunity or a delay in diagnosis” of Campbell’s endocarditis.

“That has been admitted by the trust,” Golombek added. “However, it’s also part of the evidence that this particular missed opportunity or delay in diagnosis would not have more than minimally contributed to Kevin’s death on the balance of probabilities.”

(Top photo: Shaun Botterill/Allsport)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment