Historically, Bayern Munich have always had the upper hand over Inter at San Siro.

In their previous four competitive matches in Milan, the German side were victorious in each one of them.

That’s why Harry Kane’s opener in the second leg of their Champions League quarter-final tie gave the impression that history might be repeating itself.

Advertisement

However, it took Simone Inzaghi’s side only nine minutes to turn things around before Eric Dier’s equaliser made it 2-2 — a scoreline that put Inter in the semi-final after their 2-1 victory in Munich.

Both Inter’s goals on Wednesday came from two outswinging corners, which raised their tally to 16 goals from corners in all competitions this season.

Attacking corners have been an important tool in Inter’s search for another Serie A title, with their 11 goals from corners being the most in the division this season. Their effectiveness from this position has helped them to the top of the table, three points clear of Napoli in second, with six games to go.

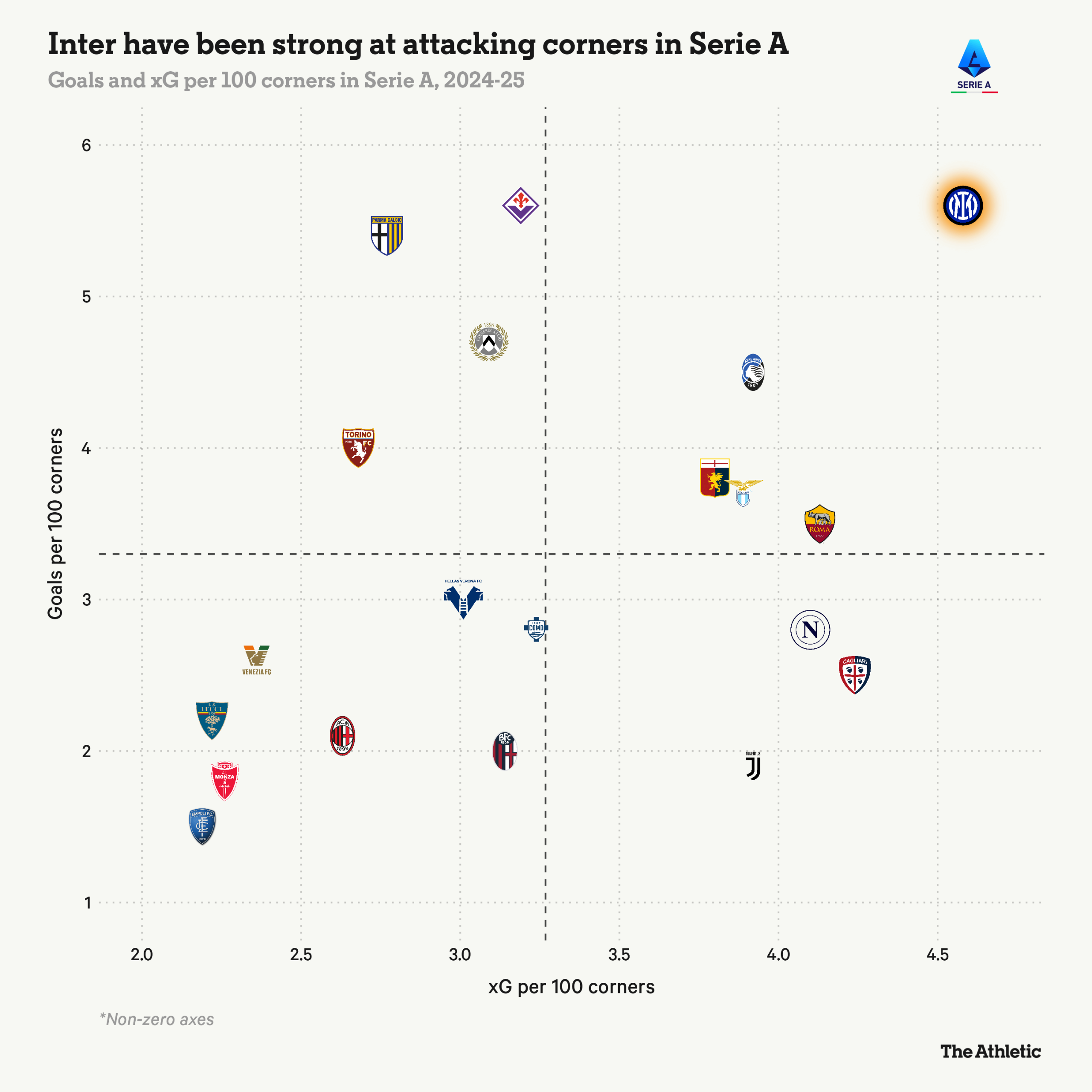

Even taking into account the number of corners each team has been awarded, Inter still top the charts with 5.6 goals per 100 corners in the 2024-25 Serie A campaign.

The underlying numbers also illustrate that Inzaghi’s side has been regularly creating high-quality chances from corners. Their rate of expected goals (xG) per 100 corners (4.6) is the best in Serie A this season.

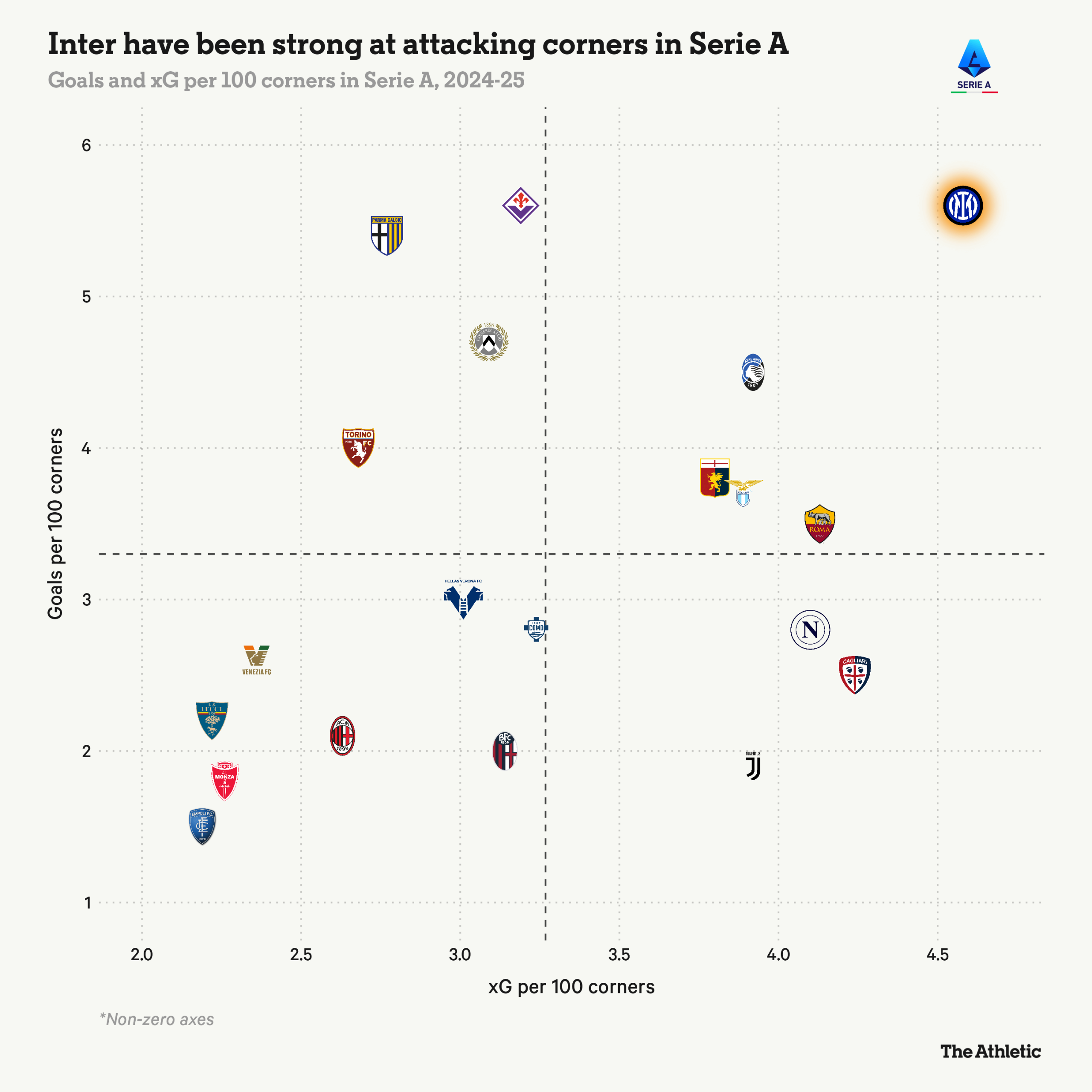

The majority of Inter’s corners (57 per cent) in the league this season have been outswingers, and that type of corner targeting central and near-post zones just outside the six-yard box has been instrumental to the team’s success.

Hakan Calhanoglu and Federico Dimarco’s pinpoint deliveries have been the main catalyst behind Inter’s threatening corners, and the team’s attacking setup plays to the strengths of the individuals.

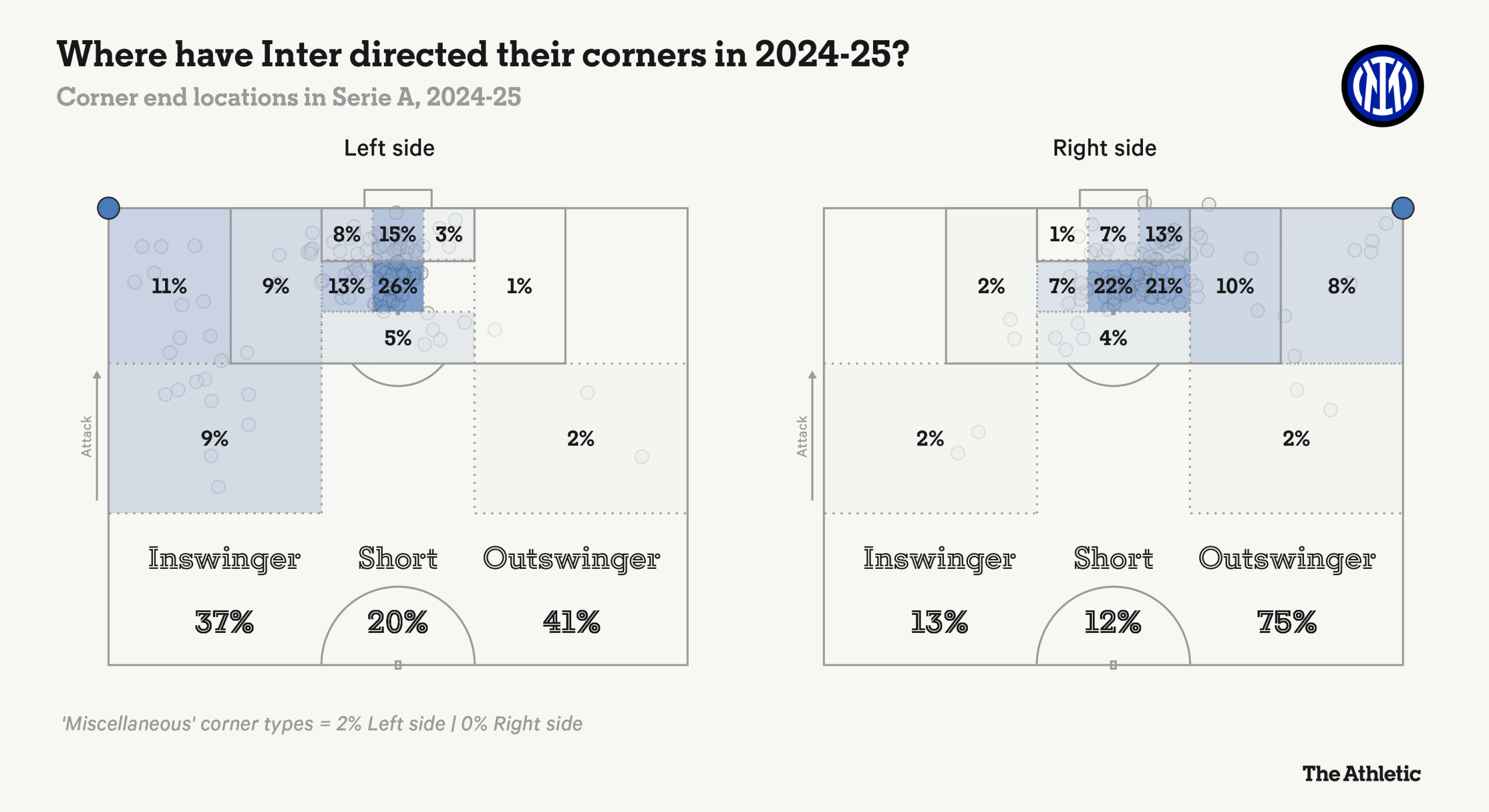

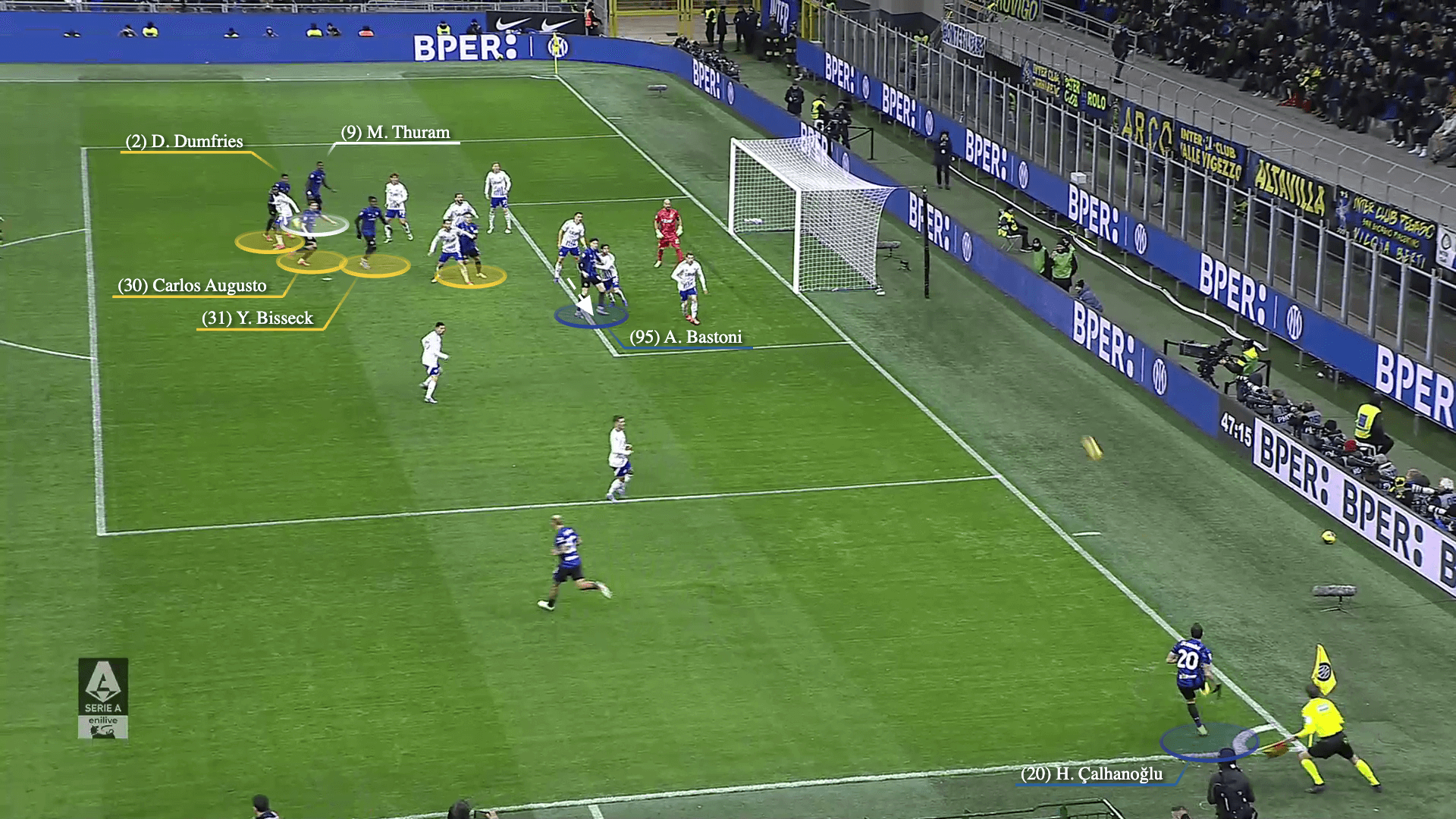

On outswingers, Inter usually position Alessandro Bastoni by the edge of the six-yard area while the rest of the pack stay behind him.

Bastoni’s role is to attack the near post while disrupting the opposition marking that area. Near the penalty spot, Inter’s runners (yellow) split in a diagonal line to frame the incoming cross.

By positioning themselves in a diagonal line, Inter’s players are able to attack the path of the outswinging cross from different heights and at different timings, which means that if one player misses the header there is someone else coming after him.

This is called ‘framing the cross’ and it provides unpredictability as well as options.

The last part of the puzzle is Marcus Thuram, whose main task is to attack the far post to be in position to score from the flick-on or the rebound.

In this example, against Como in December, Inter’s diagonal line connects with Calhanoglu’s out-swinger…

… and Carlos Augusto heads the ball into the back of the net without needing Thuram.

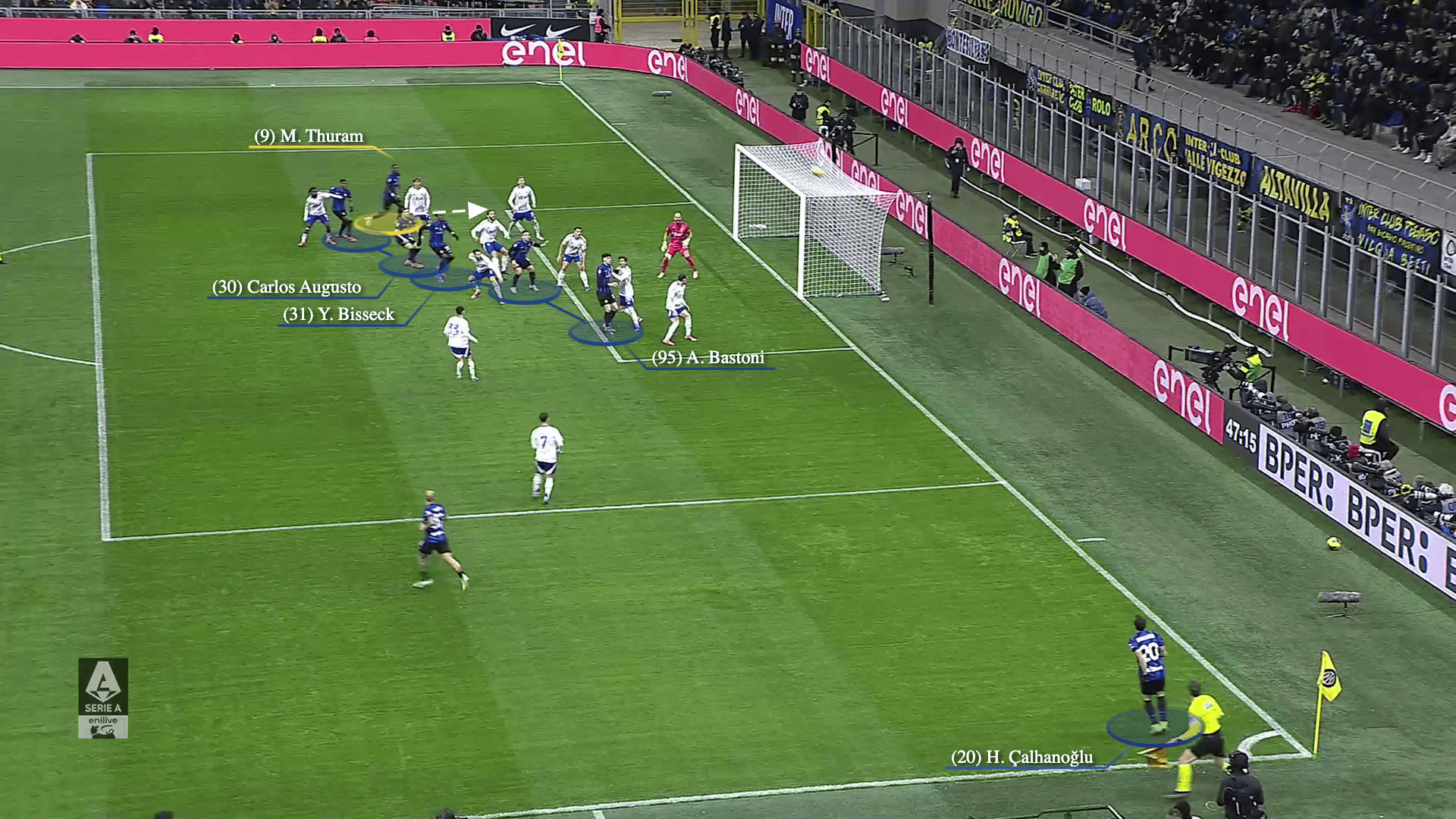

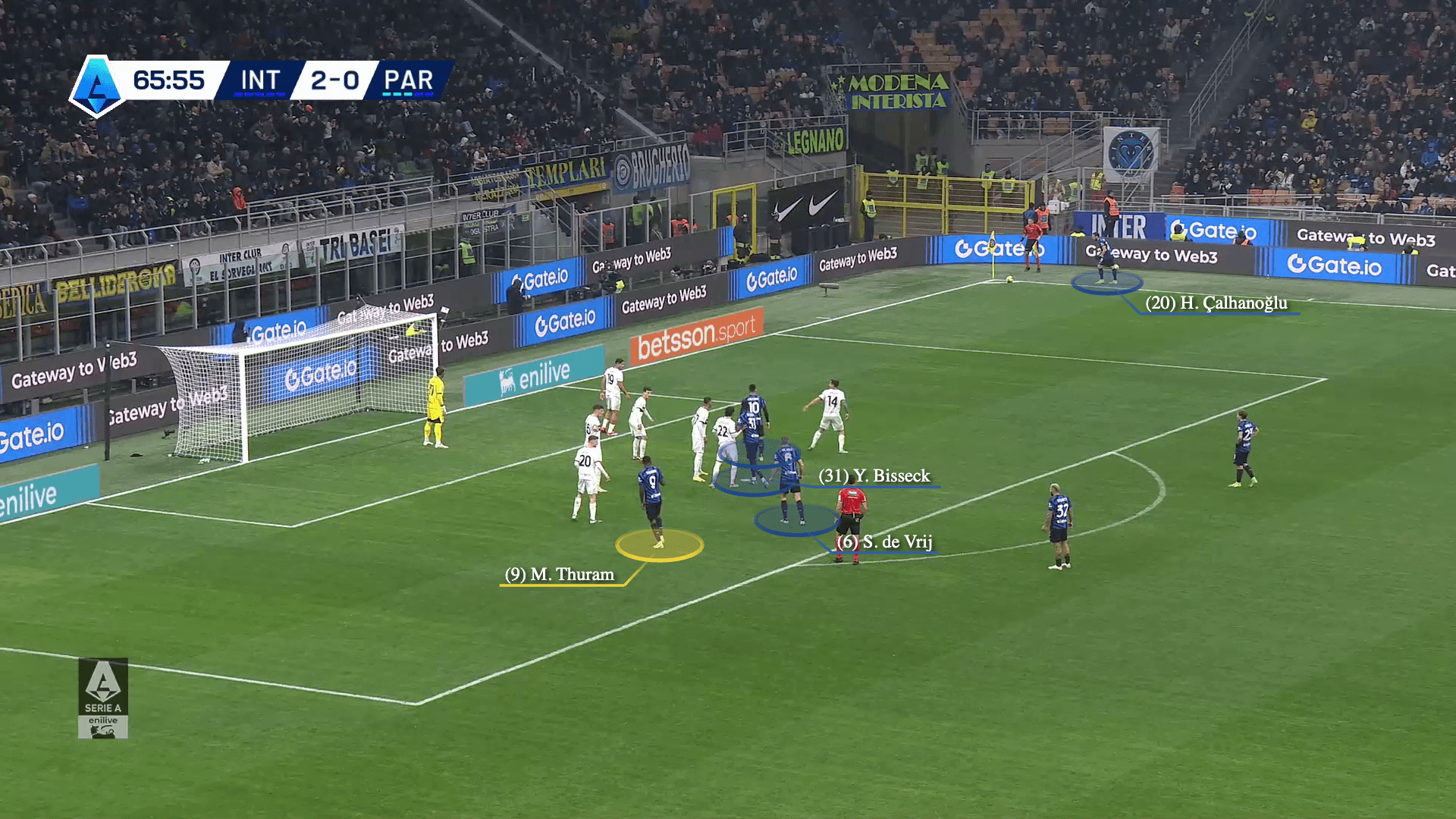

In another example, against Parma in the same month, the setup’s insurance policy in Thuram pays dividends.

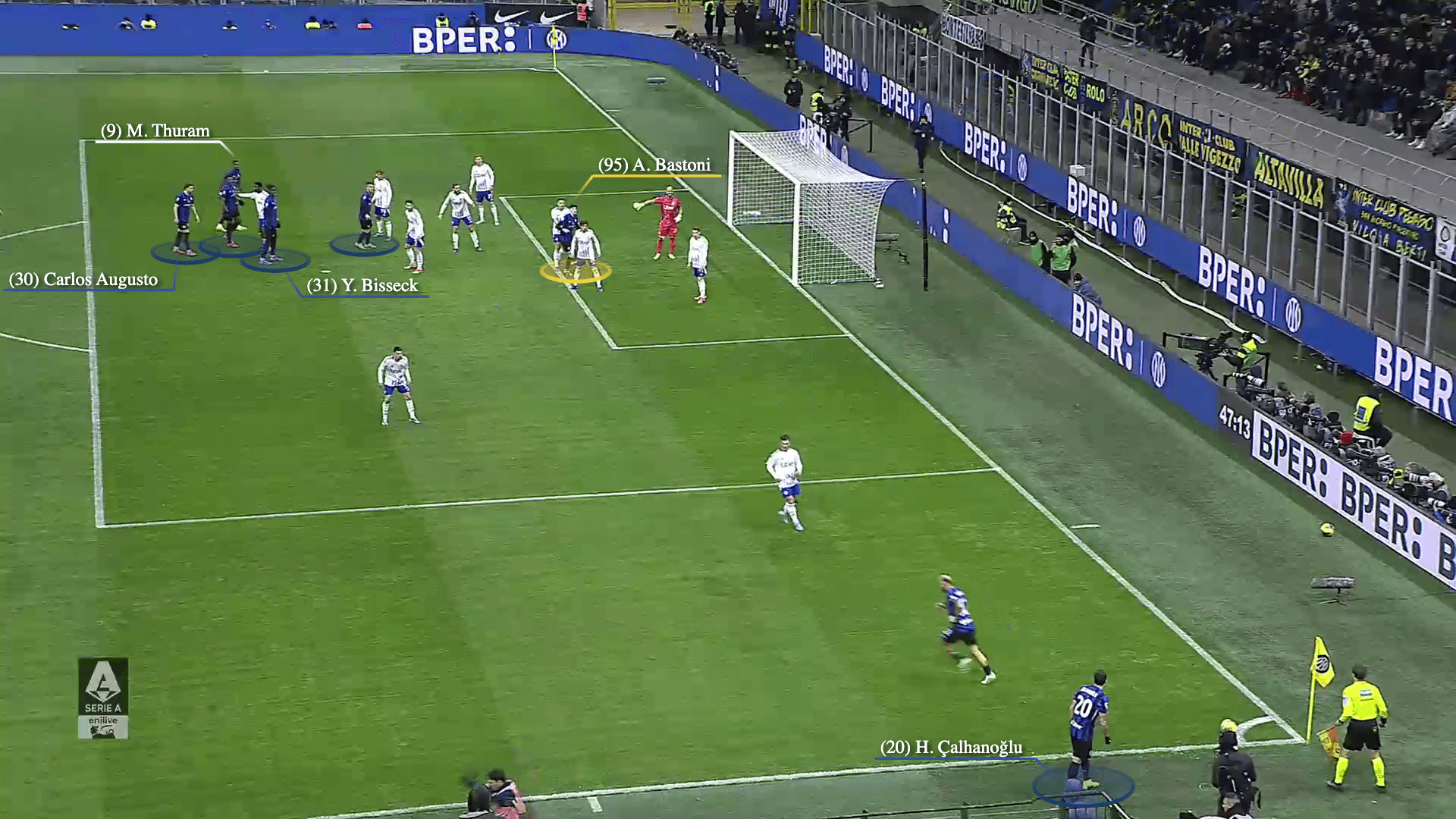

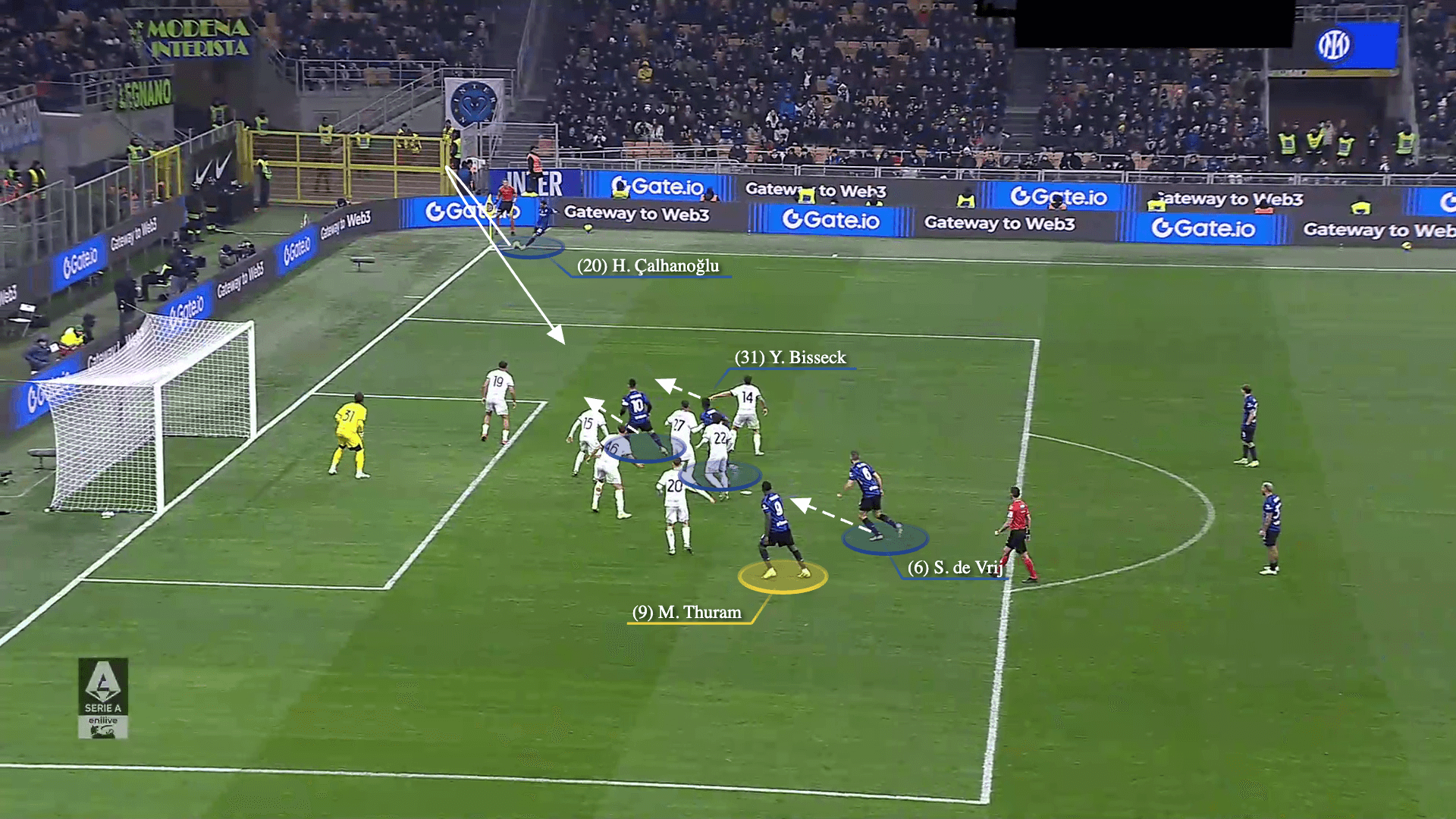

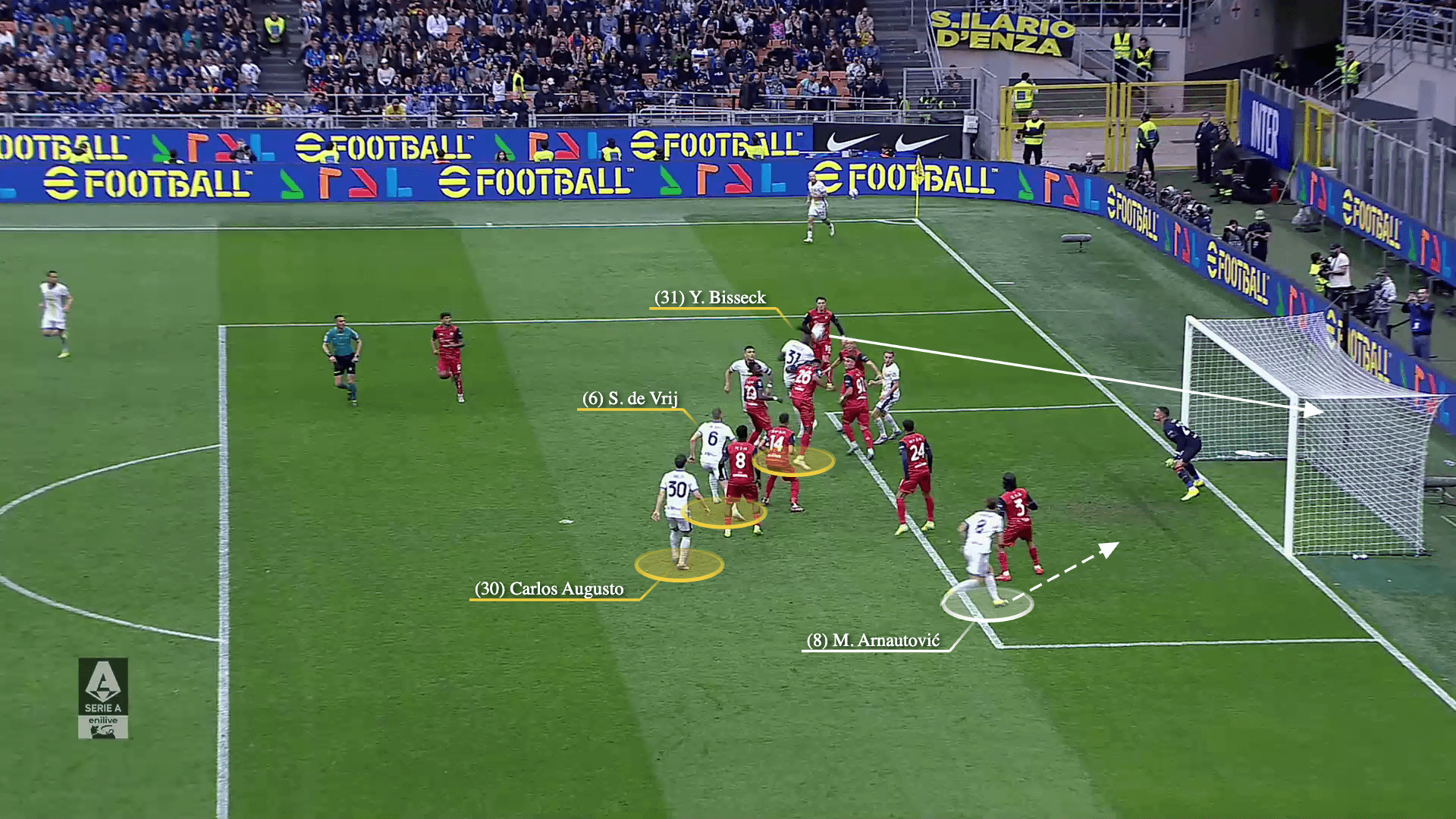

Against Parma’s zonal-oriented defence, Lautaro Martinez, Yann Bisseck and Stefan de Vrij are the diagonal attackers while Thuram is initially positioned towards the far post.

When Calhanoglu plays the outswinger, Inter’s diagonal runners attack the path of the cross from different positions and at different timings as Thuram readies himself to dash into space.

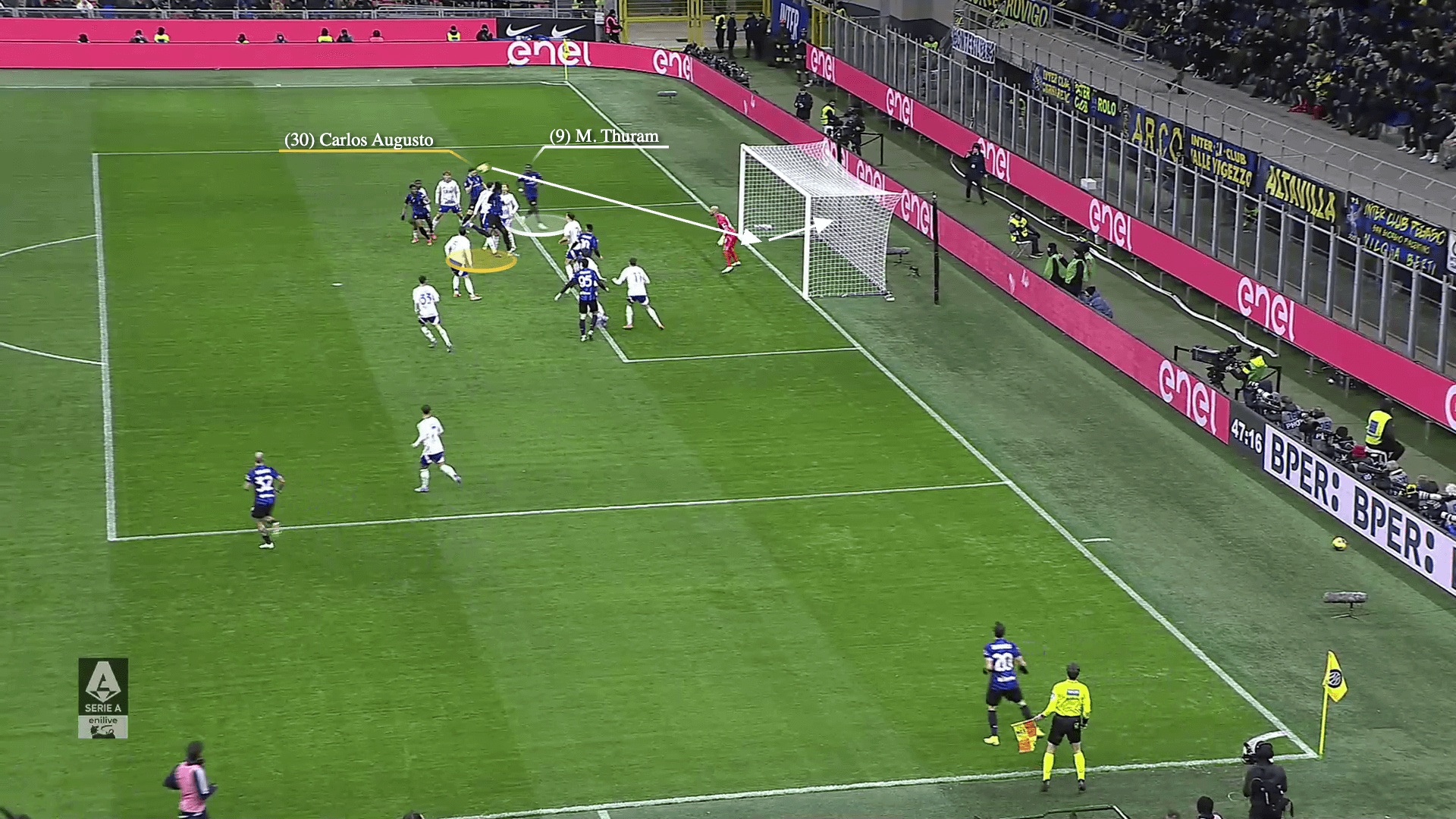

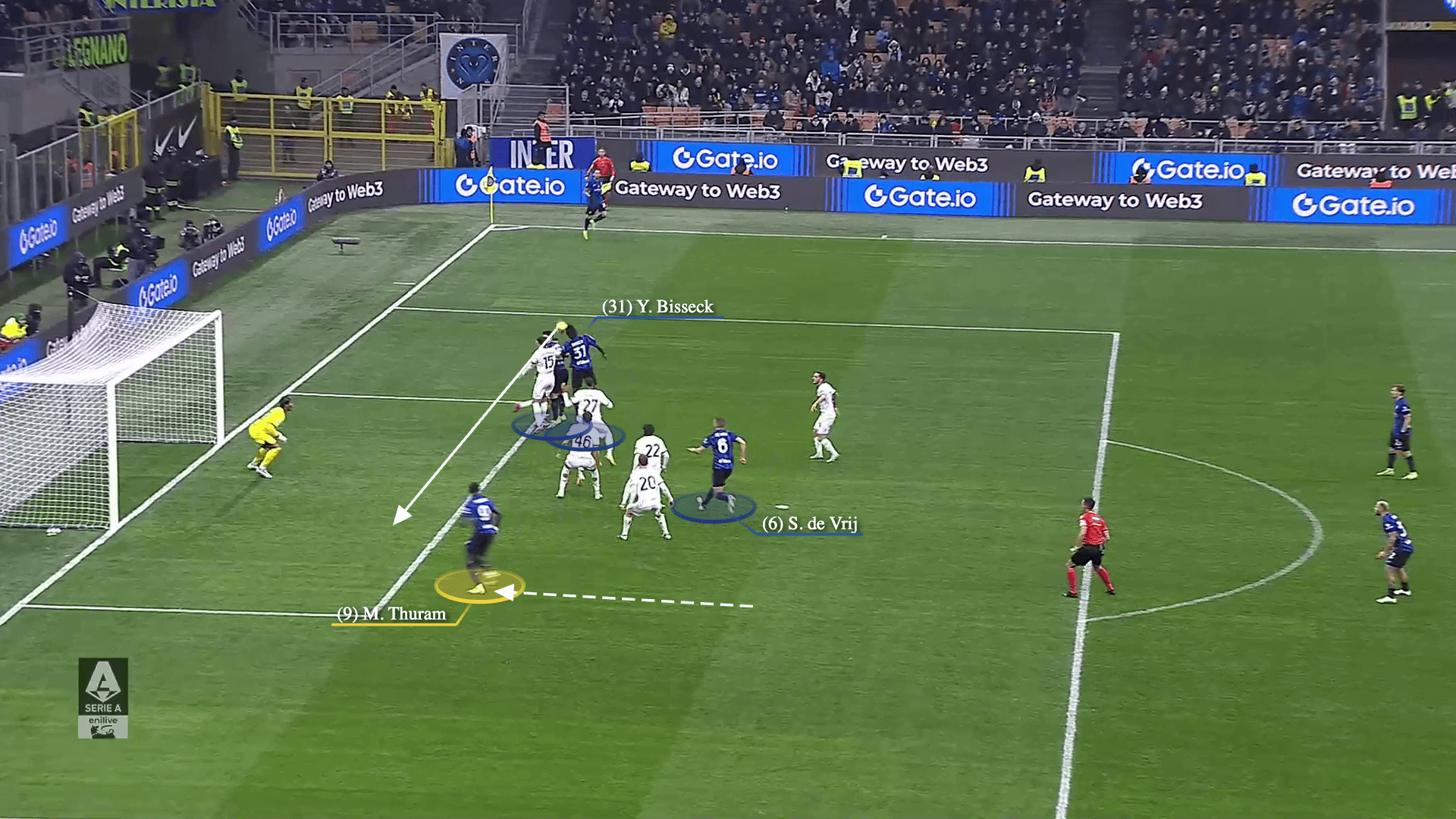

Before the ball reaches Bisseck, Thuram runs towards the far post to be in his designated position. The Germany centre-back then beats the near-post defenders and flicks the ball towards his centre-forward…

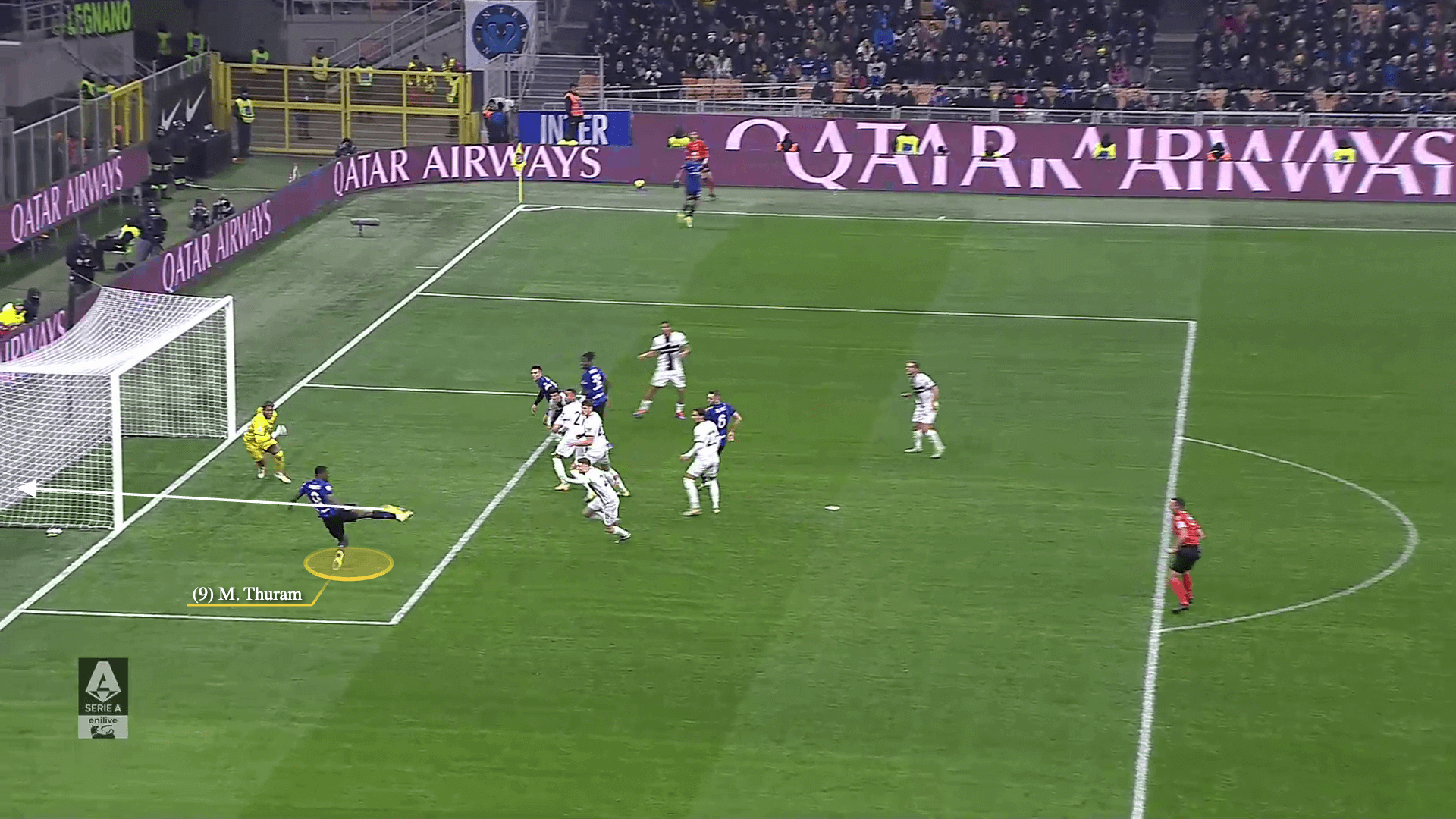

… who scores from close range.

Another advantage of this offensive approach is that Inter’s diagonal players are running towards the cross, and therefore gaining momentum that will help their jump against static defenders — especially zonal-oriented defensive organisations.

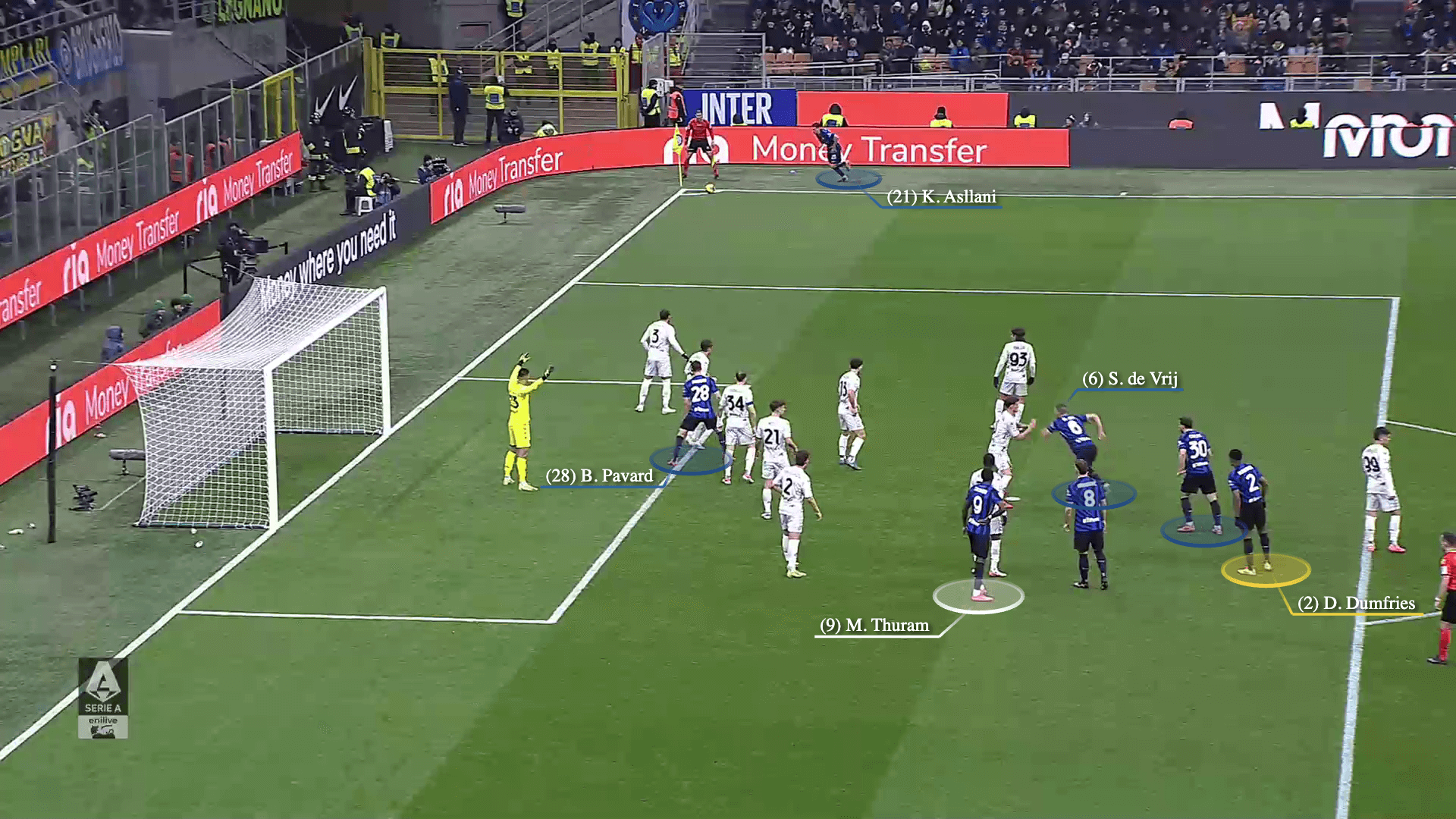

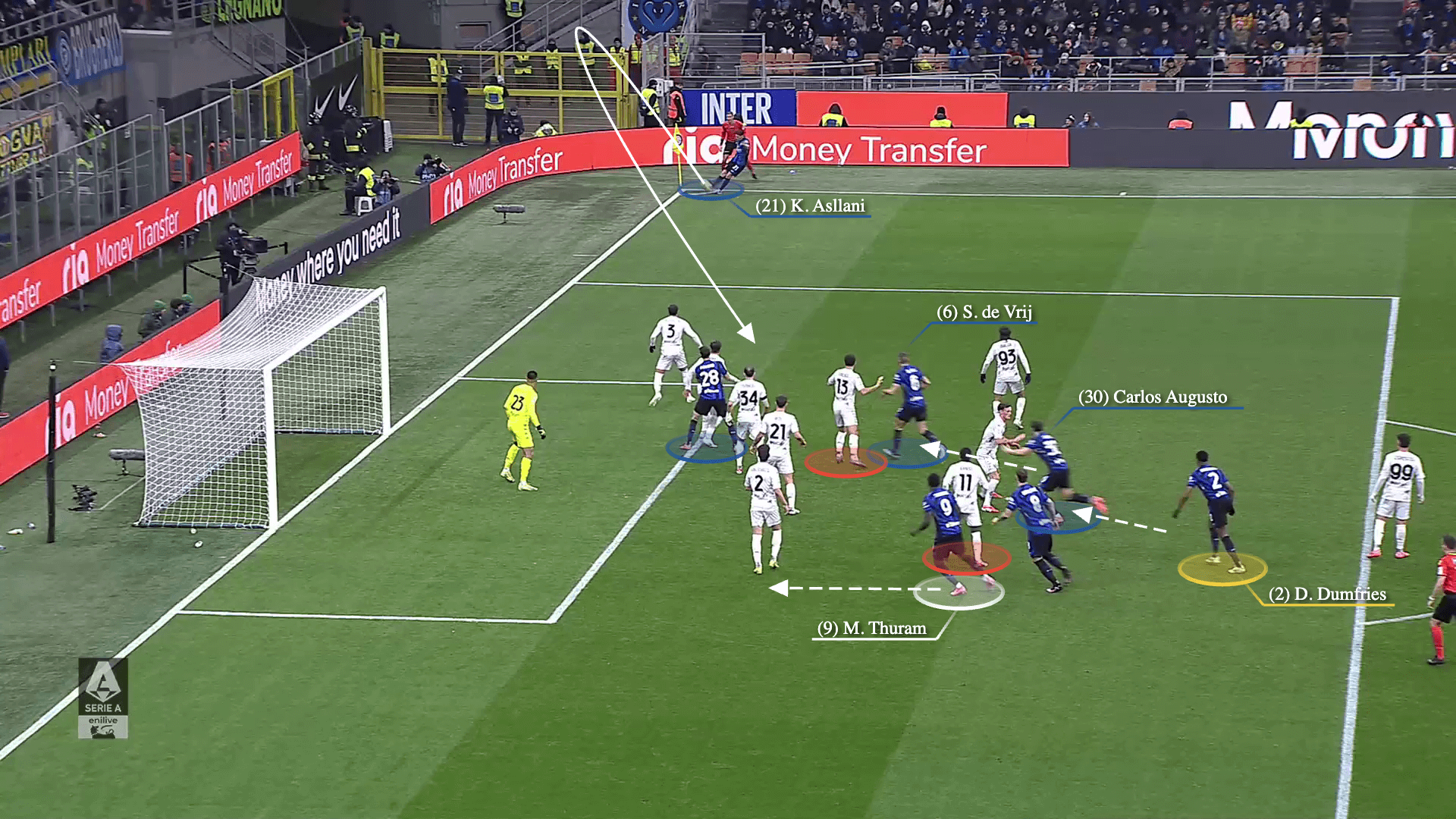

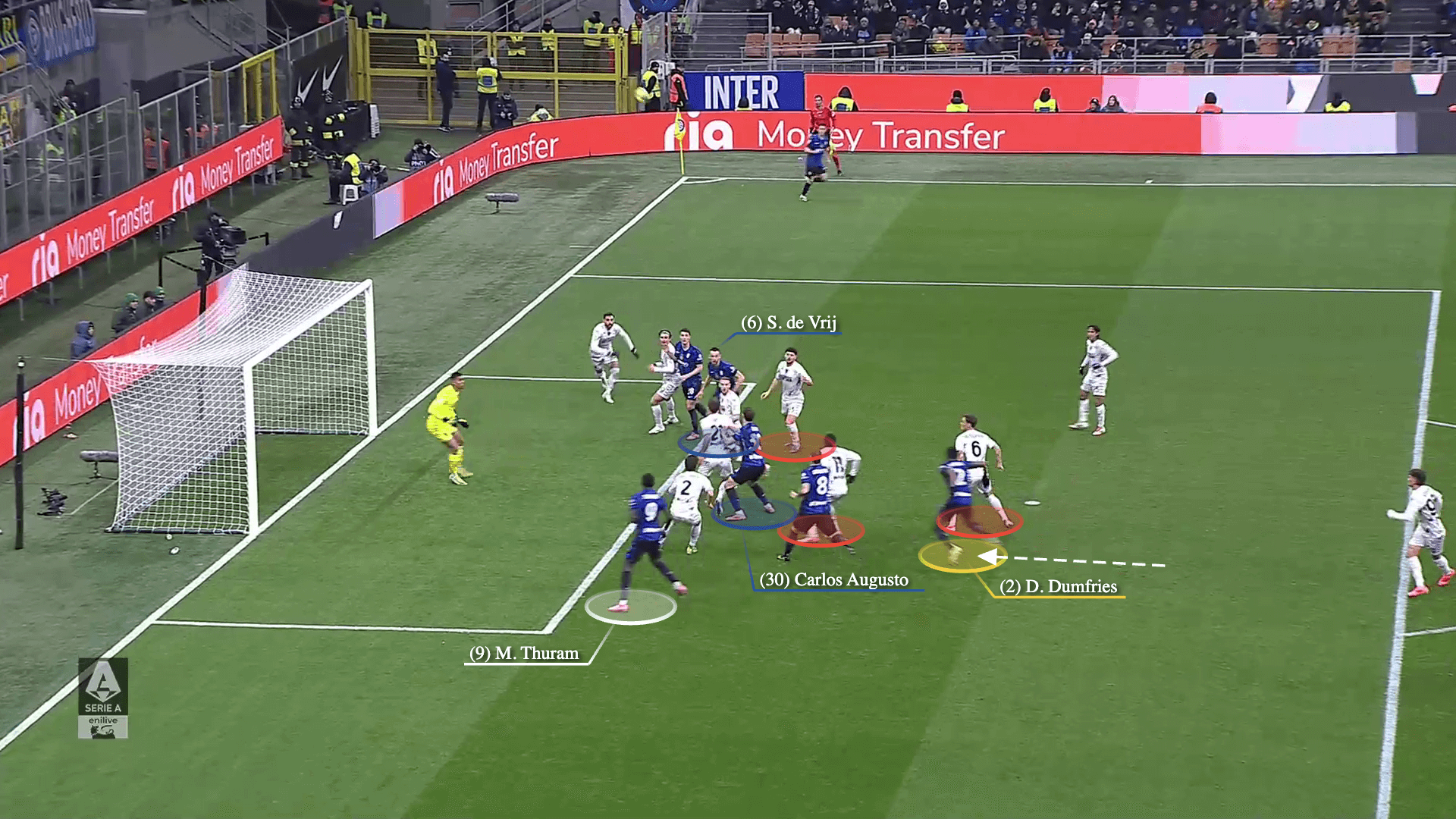

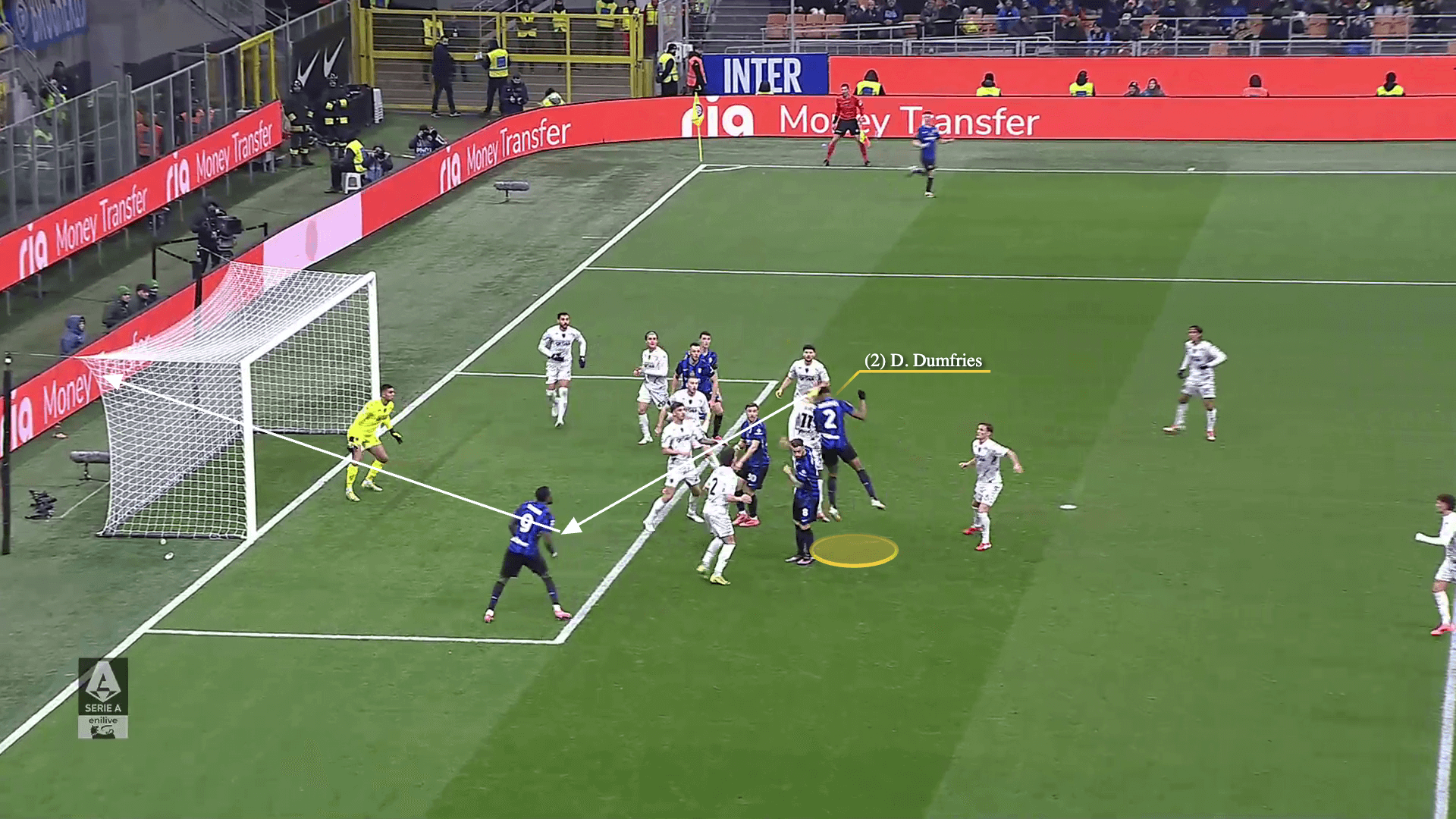

In this example, against Empoli in January, Benjamin Pavard is by the edge of the six-yard area, Thuram is positioned towards the far post, and De Vrij, Augusto and Denzel Dumfries are ready to attack the cross.

As Kristjan Asllani curls the ball towards the target zone, the movement is textbook: Pavard (Inter No 28) disrupts one of the near-post defenders, Thuram dashes towards the far post, and the diagonal runners lag their movement to attack the cross at different moments.

De Vrij moves first, then Augusto follows, which confuses Empoli’s second line of zonal markers (red) as Dumfries patiently waits for the right time to pounce. The Netherlands centre-back occupies Liberato Cacace (Empoli’s No 13, highlighted in red)…

… and the other zonal markers in the second line (red), Emmanuel Gyasi and Liam Henderson, are distracted by Augusto’s run and the trajectory of the cross. This is the moment Dumfries surges forward…

… and attacks the cross to double Inter’s lead.

The stacking of the runs coupled with attacking the path of the cross dismantles Empoli’s zonal markers because it enables Dumfries to attack the cross at a time when he is free and able to generate momentum to have a higher jump.

Even against a matching line of zonal markers it’s still a tough task because Inter’s diagonal runners constantly have the ball in their sight because of the trajectory of the delivery and their initial positions. Meanwhile, the opposition can’t see the ball and Inter’s diagonal runners at the same time.

Advertisement

Last Saturday, Inzaghi’s side scored yet another out-swinging corner in the 3-1 victory against Cagliari.

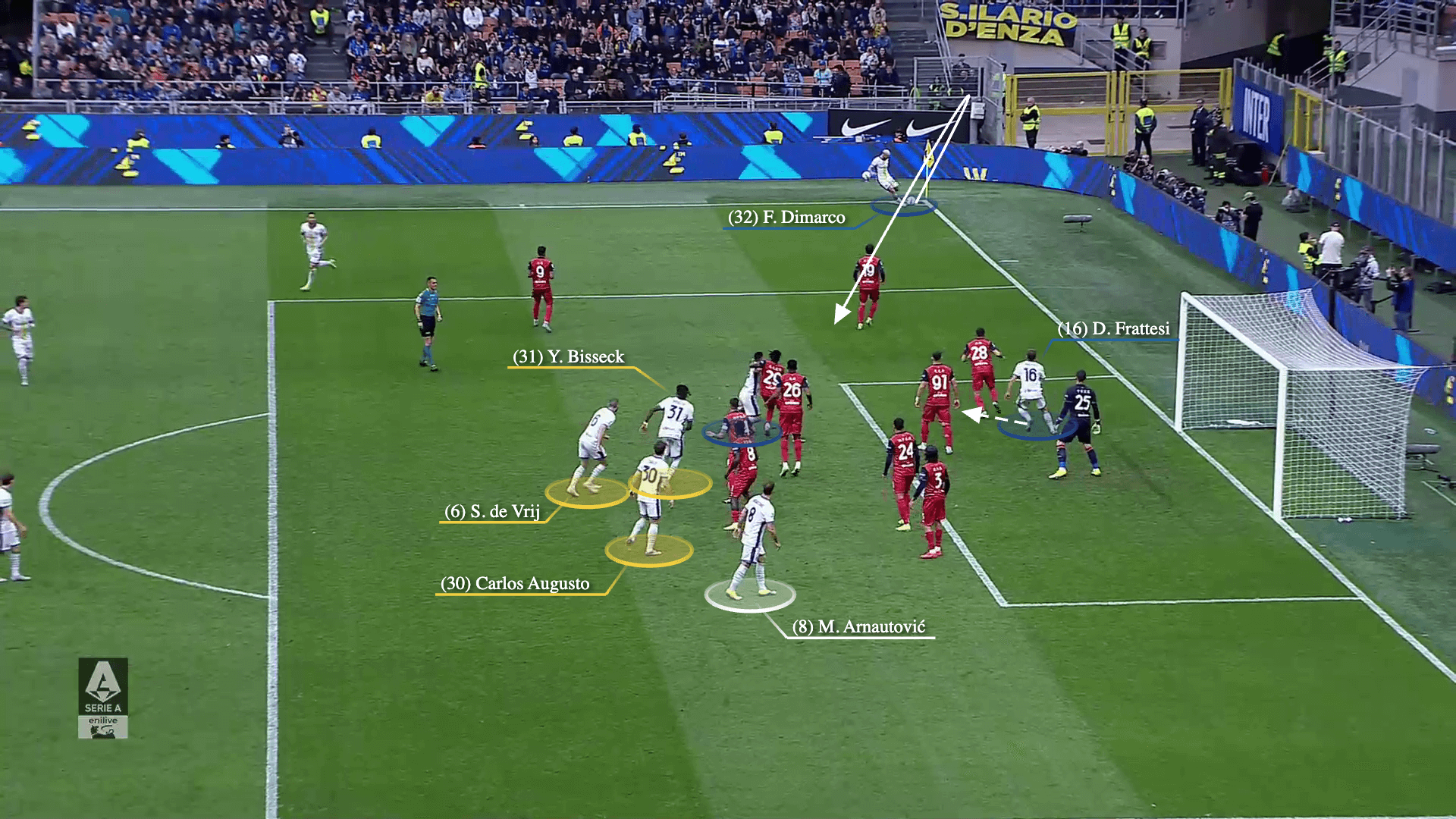

Here, Martinez, Bisseck, De Vrij and Augusto are readying to attack the cross…

… and they adjust their positions to the trajectory without the fraction-of-a-second delay of rotating their head because they have the ball in their sights the whole time. On the other hand, Cagliari’s second zonal line is merely reacting to the situation because they can’t see the ball and Inter’s runners at the same time.

This enables Bisseck to beat Yerry Mina to the ball and head it into the net, with De Vrij and Augusto in perfect positions to attack the out-swinging cross while Marko Arnautovic is the insurance policy towards the far post.

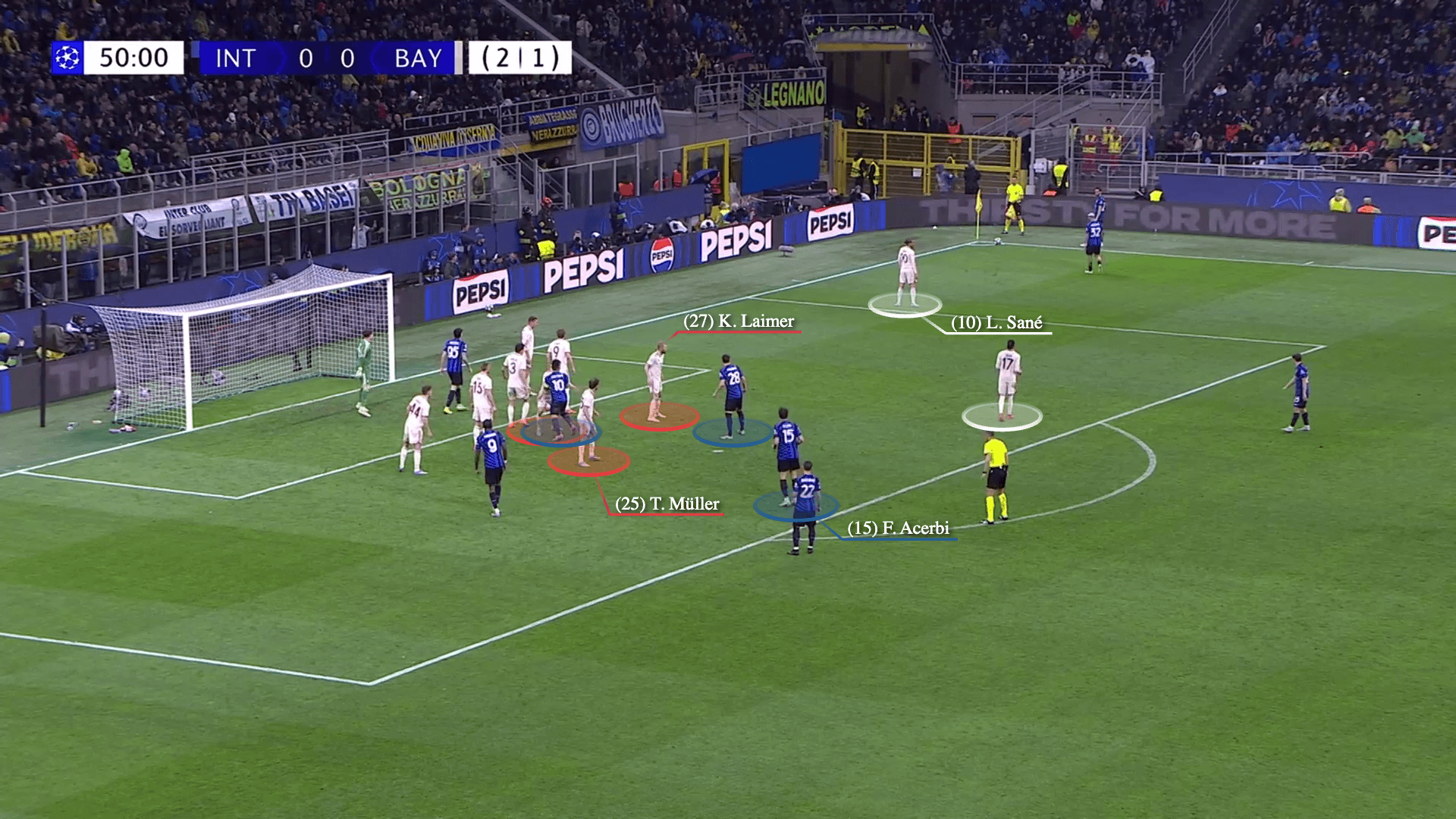

In the 2-2 draw against Bayern, Vincent Kompany’s side defended Inter’s outswingers with five zonal players by the edge of the six-yard box, Leroy Sane and Michael Olise in positions to stop the short option or a late runner, and Konrad Laimer, Joshua Kimmich and Thomas Muller man-marking Pavard, Martinez and Francesco Acerbi.

It didn’t work, though, because on the first goal Kimmich couldn’t follow the trajectory of the outswinging cross and Martinez at the same time.

As the ball is in the air, Kimmich has his eyes on Martinez who can clearly see the trajectory of the cross and adjust his position accordingly.

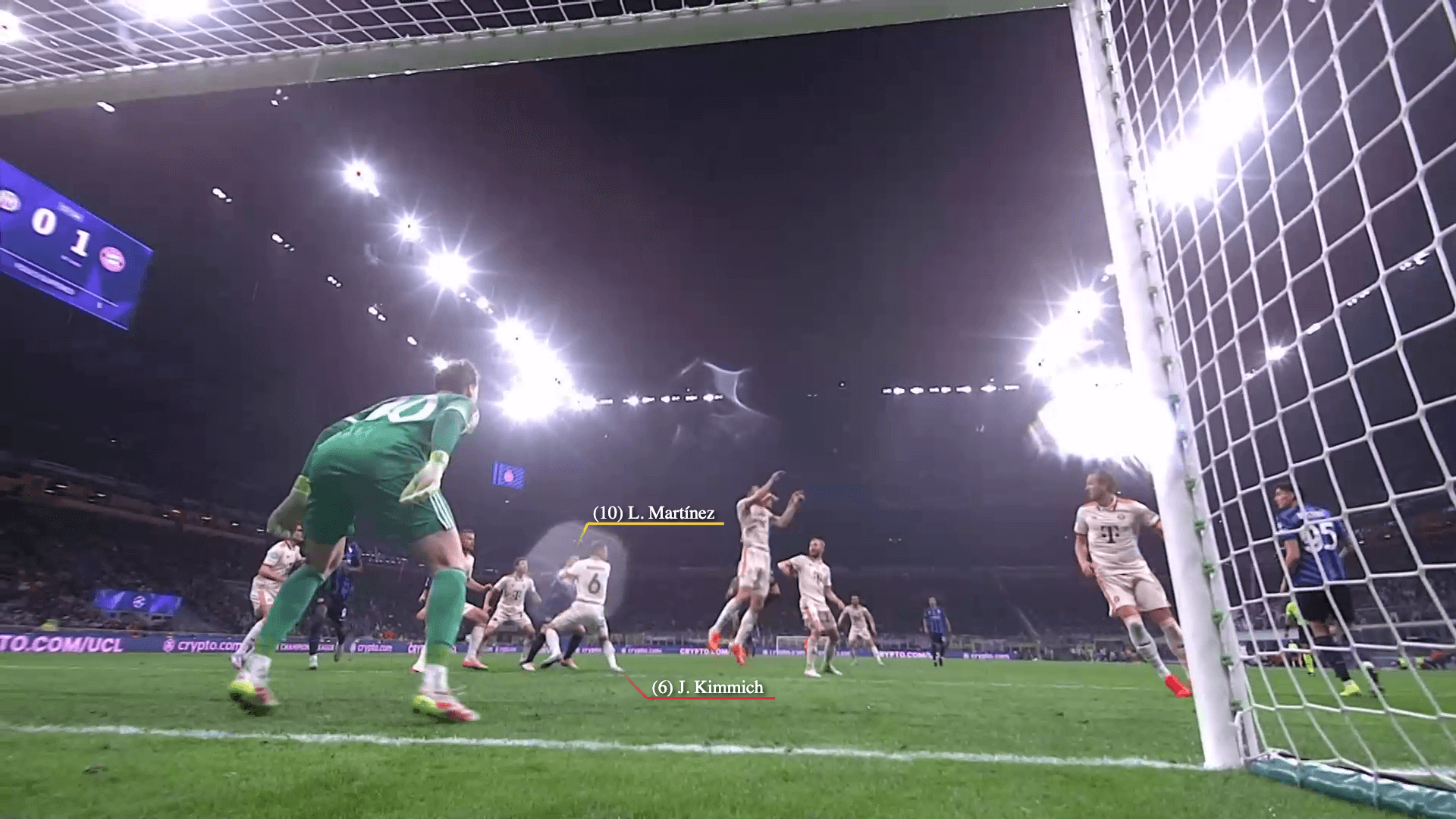

The moment Kimmich turns his head to have a glimpse of the ball is the moment Martinez distances himself from the Germany midfielder. Inter’s centre-forward then clumsily connects with the cross…

… before striking the loose ball into the bottom corner.

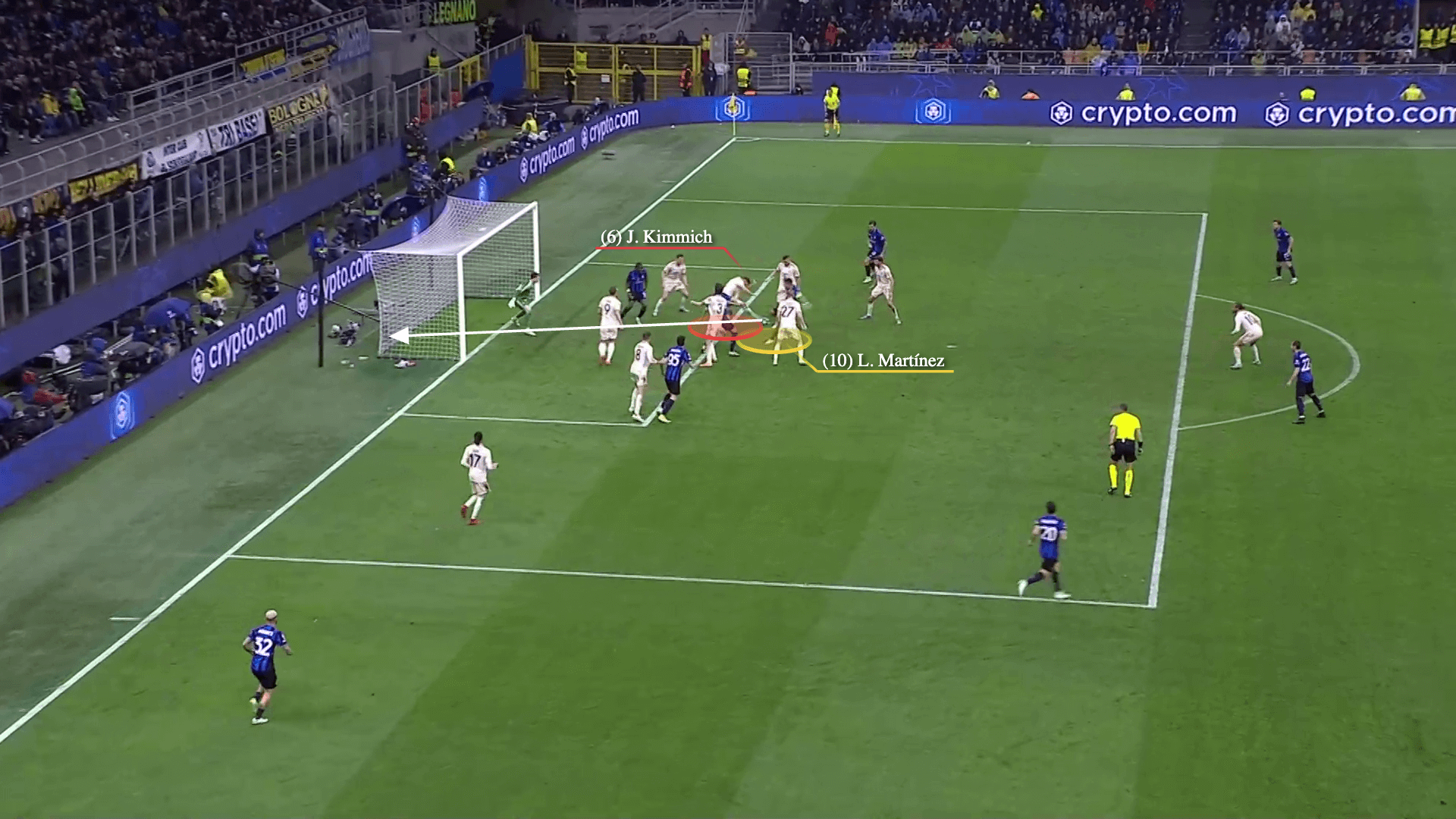

Inter’s second outswinging corner was cleaner.

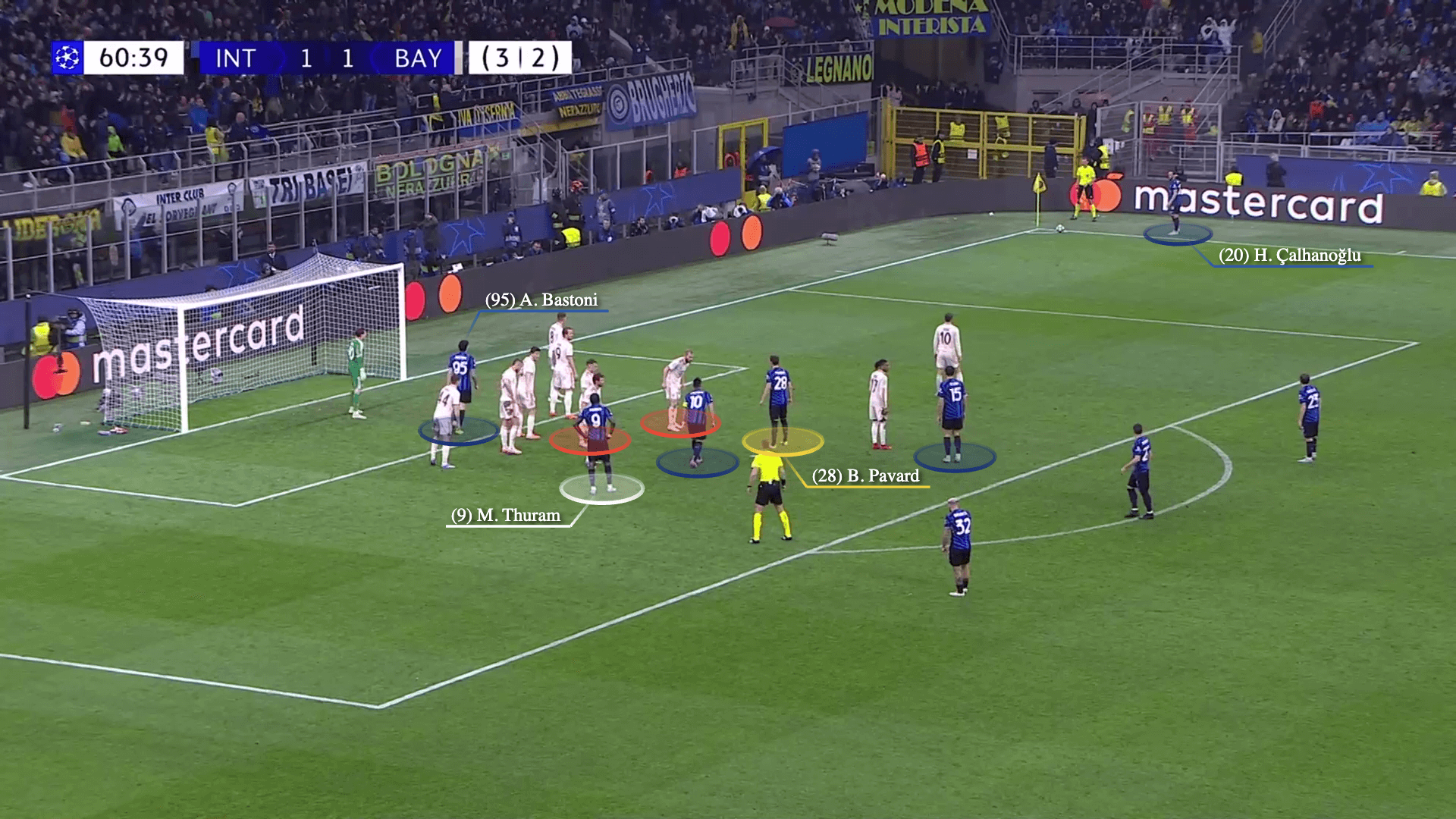

Again, Inzaghi’s side is starting in their familiar setup with Bastoni inside the six-yard box and runners behind him.

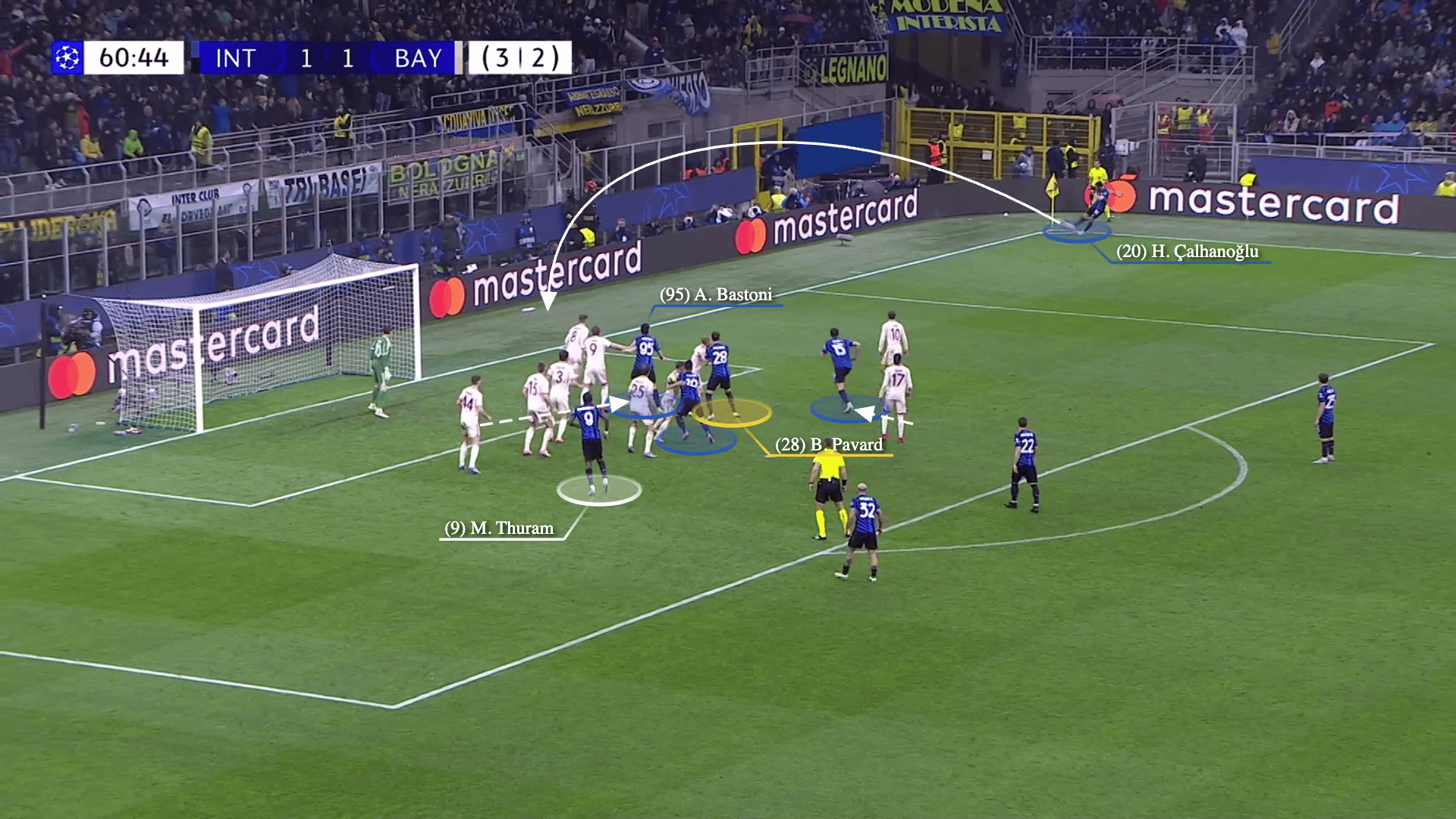

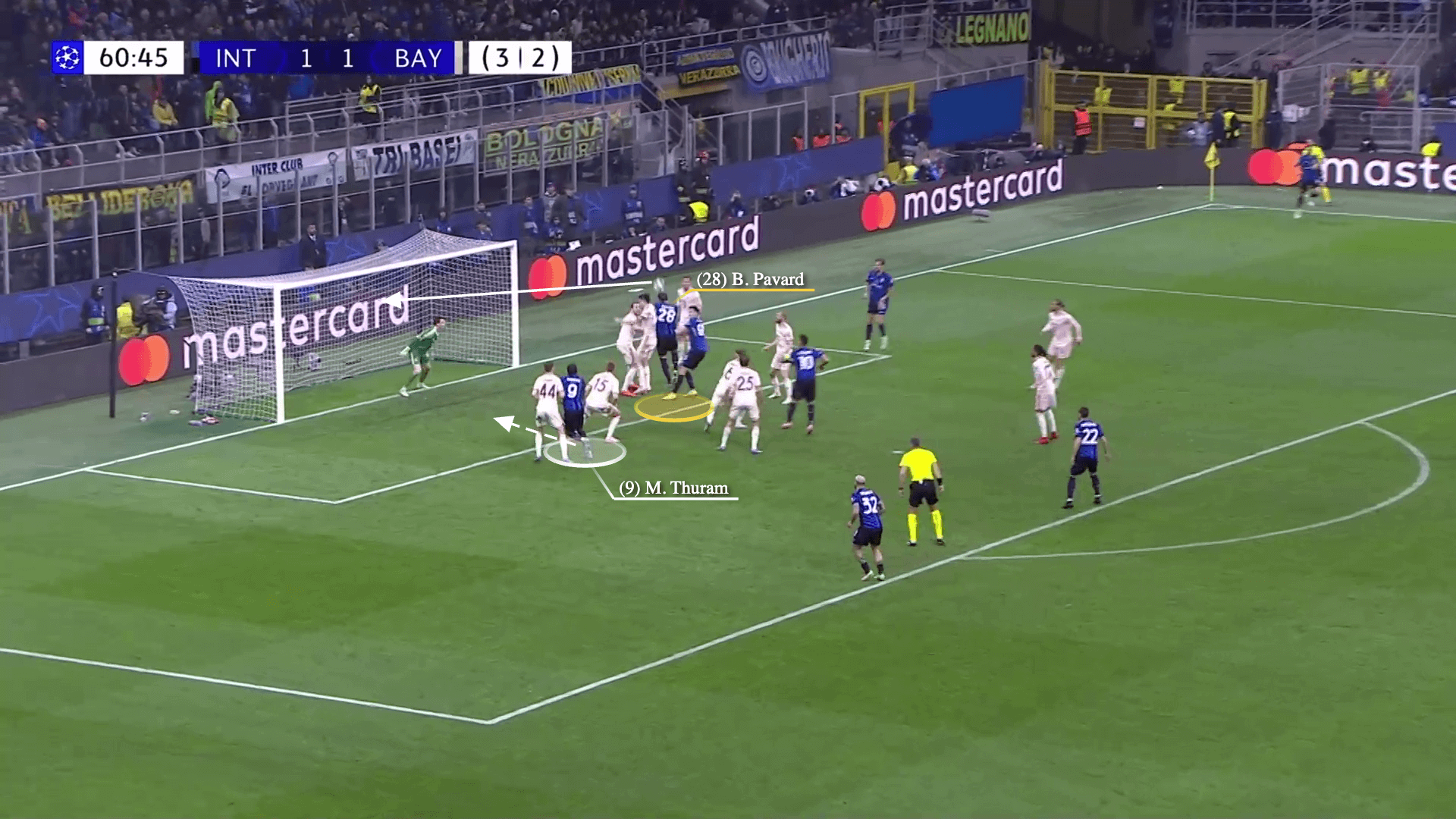

As Calhanoglu readies to take the corner, Bastoni dashes forward to occupy Kane while an unmarked Acerbi runs towards the near post. The trajectory of Calhanoglu’s cross is beyond that area, but because Inter are stationed in different positions to attack its path, Pavard is the second option.

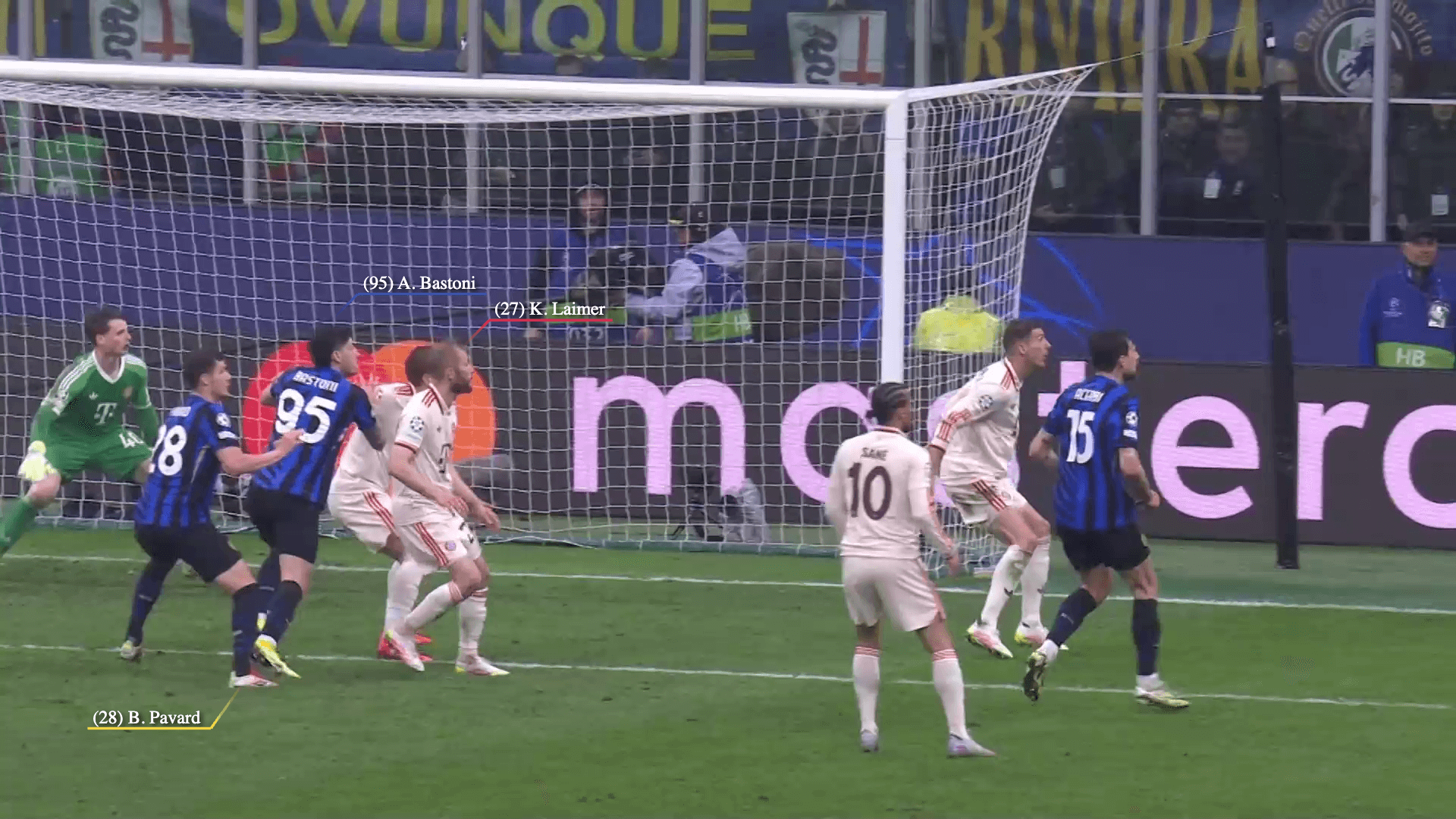

The right centre-back escapes Laimer’s marking when the Austria midfielder solely focuses on the cross, which Pavard can see while adjusting his position.

Pavard then heads the ball past Jonas Urbig to score the goal that clinches Inter a semi-final spot in this season’s Champions League.

By scoring their first two corner goals in the Champions League this season, goals from Inter’s attacking corners have now featured in all their competitions.

The outswinger in particular has been instrumental to their success in 2024-25, as Inzaghi’s side eyes a historic treble.

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment