For his first day of work in June 1999, Scott Smith arrived at the makeshift bat factory, a three-level brick corner house in Ottawa with a stop sign sprouting up from the tree-lawn shrubs.

Sam Holman handed Smith an order form: six bats, all for Jose Canseco.

Holman handled the first one. Then, it was Smith’s turn. Craftsmanship isn’t for those with trembling hands and pitter-pattering hearts. Smith’s initial attempt at a handmade bat didn’t go well, and Holman was irate.

Advertisement

“I was thinking my career might last for a half hour,” Smith says.

Smith asked if he could start with a simpler assignment.

“Nope,” Holman replied, “Canseco needs these bats. We’re making them today.”

Every minute was precious in those nascent days of Sam Bat, after Holman discovered that maple bats, not just the century-old standard ash models, could meet professional hitters’ needs. Holman upset the stasis of the bat industry, and in his 300-square-foot garage, as business boomed, he and his motley crew hustled to meet demand.

“It was sink or swim,” Smiths says. “Some of the swimming looked pretty awkward, but we stayed above water.”

Torpedo bats have become the rage in 2025, but before this latest craze, there was maple mania in the late ’90s. Despite rival companies insisting, Smith says, that maple was merely a fad, it stuck a landing in a sport resistant to change. In fact, more than three-quarters of big-league hitters now use maple. Those same manufacturers that once doubted its staying power ultimately adopted it themselves.

And it’s all because of Holman — with a request from a scout, an assist from a big-league slugger and the pursuit of a home run record.

“He didn’t have children,” said Arlene Anderson, Holman’s business partner. “This was his baby.”

At the time, Holman was an unassuming guy in his early 50s, with a South Dakota drawl and denim overalls. He spent 24 years as a stagehand at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, where he dealt with musicians, dancers and actors, including Donald Sutherland and Karen Kain. Those interactions prepared him for his connections with major leaguers. The carpentry work he completed in his role prepared him for the assignment that would change his life — and upend the sport.

Holman and Bill Mackenzie, a Colorado Rockies scout, met at the Mayflower Pub, an Ottawa haunt Smith managed until he joined Holman’s outfit. They tossed back a few Creemore beers any night Mackenzie wasn’t parading around Florida with his radar gun during spring training.

Advertisement

Mackenzie once brought Holman along on a scouting trip to upstate New York to watch a high school freshman who threw 85 mph. The teen had a scholarship offer from MIT, and Mackenzie urged him to accept it rather than focus on pitching. Holman admired his friend’s candor, and when Mackenzie presented him with a challenge, Holman felt compelled to find a solution.

In 1996, after a day of watching one ash bat after another splinter, Mackenzie settled into his barstool and said to Holman: “Why don’t you do something about it?”

The next day, Holman started a crash course in bat science. A professional hitter would turn an ash bat into a broom, he says, in a week to 10 days. He figured he couldn’t make a sturdier ash bat. Those had been perfected since the 1880s, when it took six balls to draw a walk. He needed a different source of wood. He visited Ottawa’s patent library and the National Research Council, where he learned the density of maple isn’t too different from that of ash. Maple has a tight grain structure and is a harder wood than ash, giving it the potential to be more durable.

Holman had spare maple in his home, as he was crafting new spindles for his staircase. His grandfather was a mechanical engineer who taught his grandkids how to carve with a jackknife after he carved a model of a 1927 tank truck to present to a Columbia Steel committee. So, Holman had long had a passion for woodworking. He was the perfect person for this task.

In those early days, before Holman owned a well-oiled factory to create sufficient supply, his home doubled as a workshop. They painted the bats in the basement. They boxed them up in the kitchen. They readied them for shipping in the living room. They kept records in the third-floor office.

The cramped garage was where the magic happened.

Advertisement

In the middle of the two-car space sat an XY cutting machine Holman built. Four workers crammed into the garage at a time: two to operate the machine, one to finish off the bat with hand turning and one to sand it down.

“It was like a gang of pirates got together to make the best bats in the world,” Smith says.

“We all knew each other by fart,” Holman adds.

Holman first tested his model with the Triple-A Ottawa Lynx that summer. In April 1997, he convinced a trio of Toronto Blue Jays players to try them during batting practice: Carlos Delgado, Ed Sprague and Joe Carter. Holman thought he was in “rare territory” when he arrived at the Skydome ticket gate and an employee redirected him to the player entrance.

Carter took a particular liking to them, telling Holman: “You really have something here.” MLB hadn’t yet approved maple bats, but Carter snuck one into a game and hit a home run with it.

Smith remembers thinking, “This is something out of a movie.”

MLB approved the usage of maple bats the following year.

By 1999, the bats began to spread around baseball. (Tom Szczerbowski / USA TODAY)

Holman had to master the craft, and quick. That first year, he says, he made 80 bats. The following year, 2,000. In addition to their durability, players liked the maple bats because they found that they allowed them to hit for greater power; the hardness of the wood transmitted more energy from the bat to the ball than ash.

During spring training in 1999, he called Smith to vent about how, after visiting various camps, he was drowning in maple bat orders. He had no idea how he was going to satisfy the demand. Smith joined the effort a few months later.

“Things were taking off like rocket fuel,” Smith says.

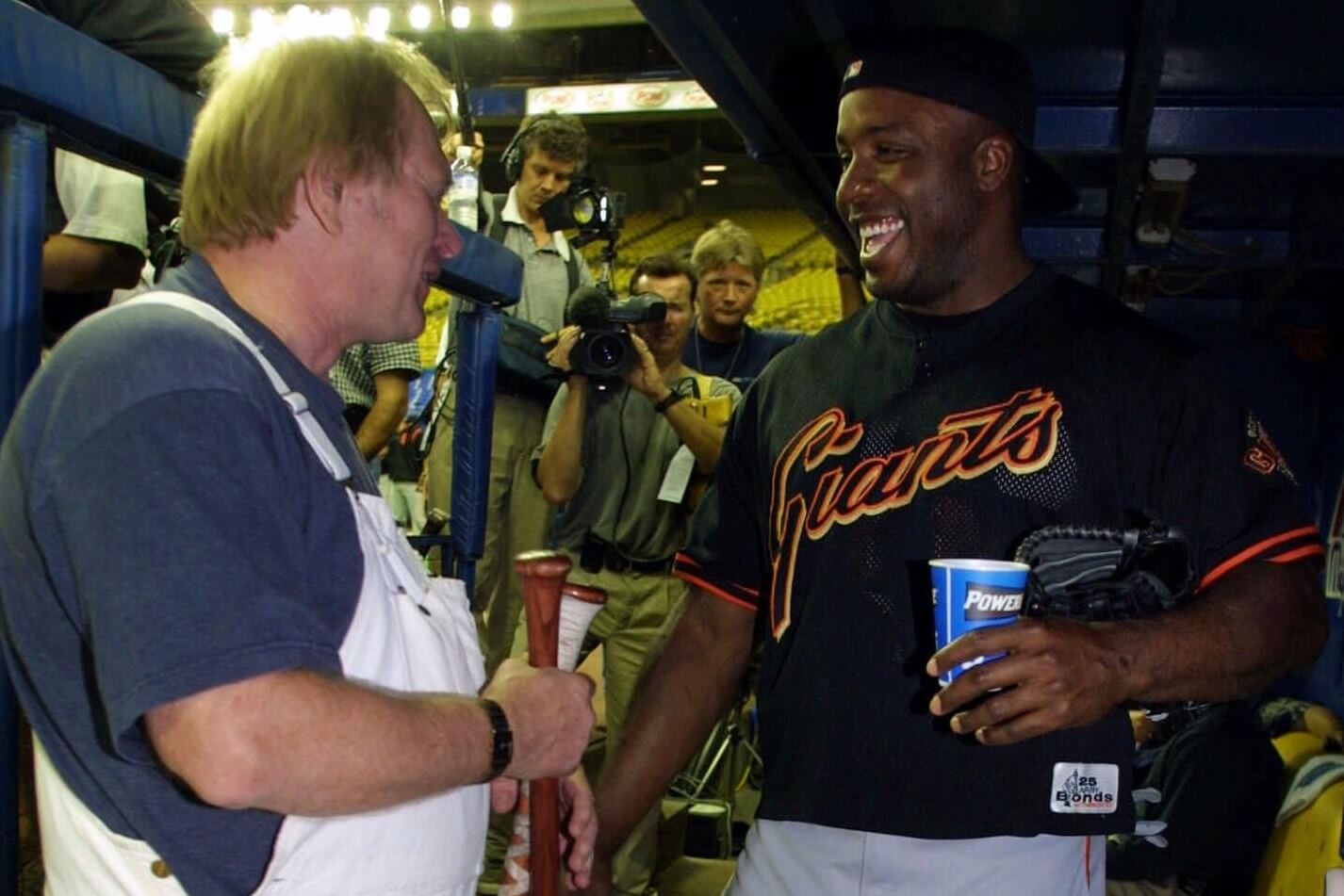

And then Barry Bonds bought in.

At their peak, they produced 15,000 bats in a year in that garage. Holman’s living room was littered with white buckets full of bats ready to be sent across the globe. When Bonds chased down the single-season home run record in 2001, business zoomed off the tracks. Holman says he borrowed $100,000 that year to spur production, but he still couldn’t keep up. He needed to move out of the garage.

Advertisement

Weeks after Bonds hit home run No. 73, Holman converted the Rochester Tavern in downtown Ottawa into his new plant. Manufacturing bats in the heart of a big city wasn’t ideal, but he vowed they’d shut down production at 5 p.m. Neighbors appreciated the gesture; they could finally sleep at a normal time without the nearby ruckus from bar-goers, and they were thrilled to be free of the urine stench left by inebriated patrons who had been known to conduct their business in the parking lot. Plus, Holman could scurry off to the Mayflower Pub for his nightly brews.

A casual endeavor originating from a conversation at a bar had swelled into a full-fledged supply chain for America’s pastime. By the early 2000s, they had clients with nearly every major-league team. A Sam Bat fueled Vladimir Guerrero and Manny Ramirez to Silver Slugger Awards and Jeff Kent to the NL MVP Award and Albert Pujols to the NL Rookie of the Year honor. Smith remembers picking up a copy of the Ottawa Sun and spotting a photo of Canseco holding a Sam Bat that had just whacked a home run.“There was a real element of surrealism to the whole thing,” Smith says.

Bonds invited Holman into the dugout at Olympic Stadium in Montreal. Holman watched him slug an opposite-field missile, a low liner that clanged off the railing in left field and, as Holman describes, nearly bounced to the venue’s roof. Holman boasts an unlimited inventory of stories; Anderson would accompany him to spring training or to the Winter Meetings and never hear the same anecdote twice as he charmed potential customers, even if some of the anecdotes sounded embellished or impossible.

Holman says he was sitting in the hotel connected to Skydome when Canseco smacked a baseball to the grill in the hotel kitchen.

“You don’t often get a steak tenderized by a baseball,” Holman says. “The chef was certainly surprised.”

Holman never turned down a media request. Smith recalls leaving at the end of his shift one day, just as a TV truck pulled up to Holman’s front yard to conduct a live interview.

“The old-world craftsman tone dropped out of him effortlessly,” Smith says.

Advertisement

Holman and his brand — more formally known as the Original Maple Bat Corporation — were highlighted in Reader’s Digest and Sports Illustrated. Before a New York Times profile was published, the author asked Holman if he could handle the 1,000 orders that would likely come his way once the story ran. No, he couldn’t. But what could he do? Everyone wanted a piece of maple.

“What’s the first thing you do if somebody’s hot?” said Kevin Rathwell, the company’s director of dealer sales. “You see what they’re swinging.”

Maple adoption was not without its bumps. At one point, MLB altered the rules around maple bat production out of concern that the hardness of the wood was causing them to break in ways that produced many sharp edges and could be dangerous. But those issues faded, production techniques evolved, and in 2018, Holman’s company even won an Emmy for supplying the bats used in a Danny Glover-narrated video aired when the San Francisco Giants retired Bonds’ No. 25.

Holman with Barry Bonds after a game in 2001. (Paul Chiasson / AP Photo)

Everywhere baseball enthusiasts looked, they saw the logo Holman’s brother designed: a black bat, with a couple of white eyes and “Sam Bat” sprawled out in all-caps across the bottom. Holman’s mother, a concert pianist, botanist and biologist, shifted her focus to baseball statistics once her son gained fame. She once called and asked if he could increase the size of the logo, as she struggled to see it on her TV. No, he told her, league rules prohibited bat logos from being wider than four inches or taller than two inches.

Nowadays, Smith heads home after work, cooks dinner, pours a glass of wine and turns on a baseball game. It’s still thrilling, he says, to watch a player hit a home run with something he designed. It remains a thrill for Holman, too, though his baseball viewership has waned over time. He knows all about the recent torpedo barrel craze, and he speaks about it with both nonchalance and an expertise he never imagined he’d wield when he was working in show business, before he became a baseball pioneer.

The Mayflower Pub no longer exists, replaced by a Scottish whiskey establishment. Holman hasn’t sipped a beer since he underwent quadruple bypass surgery four years ago.

“Water’s good for you at certain points in your life,” he says, laughing.

Advertisement

He struggles to stand and work with his hands. He’s no longer crafting bats, but he still resides in that corner house and can still walk around Ottawa, where he says, “Everybody knows who I am.” After all, he’s the only octogenarian with hints of blonde hair, he says. But it’s also because he influenced an entire sport by taking a friend’s challenge and, well, knocking it out of the park.

“I know I changed the game. Absolutely,” he says. “One hundred percent, I changed it.”

(Top photo of Holman: Todd Korol / Toronto Star via Getty Images)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment