By Eno Sarris, Brittany Ghiroli and Jen McCaffrey

Pitching is dialed in right now around baseball.

Here’s some evidence: One pitcher throws a unique changeup in August 2024, and by the next spring training, nearly two dozen pitchers are using the grip and talking about how much they love their new pitch. Pitchers, coaches, and executives are all on the same page. The tech and data are so finely tuned that they’ll all talk about the things they are doing — the presumption is that any edge they have is fleeting, and will get quickly around the league.

Advertisement

“Advantages are short-lived,” said Orioles’ assistant general manager Sig Mejdal. “It’s very hard to do something in the field publicly in an industry that’s so well analyzed and observed, and not have it get out.”

The changes in pitching development have been well documented, but, until recently, it seemed like similar “lab-grown” solutions weren’t as readily available for hitters, though a few teams, namely the Orioles, appeared to be on the cutting-edge when it came to hitting development.

Last year, we asked other teams what Baltimore was doing so well in hitting development. Teams mentioned bat speed training, “short box” competitive batting practices, and scouting for bat path — and several teams were already trying to mimic those efforts themselves. Then the Yankees’ torpedo bat craze hit the airwaves, and players and teams clamored for information and new bats, even though the bats had been around for a year or two. This week, the Orioles publicly announced a partnership with a Johns Hopkins computer science laboratory that will use computer vision to better customize bats for their players.

“This opens the door to faster iteration, better data-driven decisions, and the ability to tailor bats more effectively to players’ needs — without compromising on compliance with league regulations,” researchers Xiaojian Sun and Kevin Wu said in a press release.

That’s moving pretty quickly, while being open about something that might have been a competitive edge at one point. We’re talking about weeks for a concept to spread now, not months or years. Does this mean hitting data, tech, and development have moved into the same space as their pitching counterparts? Is baseball’s arms race evening up? Can hitters match every new pitch or strategy that pitchers develop now that they have similar processes in place?

Advertisement

We talked to people from different organizations in different roles to understand today’s hitting landscape. How are executives, coaches, players and bat scientists viewing the current state of hitter development?

The need for speed (and the right path)

It’s easy enough to correlate bat speed to outcomes. For example, you can say the slugging percentage on swings over 75 mph is 300 points higher than for swings below that velocity. But start asking those in the industry about bat speed, and caveats emerge.

Red Sox director of hitting Jason Ochart was one of the most forceful pro-bat-speed voices when those stats emerged in the public last year. He admits there’s nuance.

“Bat speed is important for everyone, but not equally important for everyone; there’s plenty of minor leaguers with enough bat speed to be good that aren’t good,” he said this spring. “But no one gets worse by swinging faster.”

That last part has become a pillar of the Red Sox’s developmental strategy.

Boston’s hitting group is currently the toast of the town, with Kristian Campbell in the big leagues and Roman Anthony knocking on the door, but they aren’t alone in innovating in this space. Bat speed training is something we heard about from Driveline, the Yankees, the Dodgers and the Orioles over the past couple of years. Boston’s group will also admit to liking it when hitters pull the ball in the air, and we heard about Vertical Bat Angle and bat path metrics from the Orioles as well. But to make measurable progress, Ochart says, organizations have to commit fully to focusing on the aspects of hitter development they believe will produce results.

“I learned that the hard way in previous situations where we did like 20 percent of everything, and no one got better,” Ochart said. “When you try to meet in the middle, it’s like, ‘Oh, I’m gonna turn the HitTrax on only for these reps. And we’re gonna do bat speed training for this small group of players in the DR and the complex.’ And then when I met the Red Sox group, everyone was like, ‘Go build it and do exactly what it is you want, and you’re going to have (our) full support.’”

Advertisement

Getting that level of buy-in from organizations can be hard at this stage of the game, because the correlation between hitter metrics and on-field success is not quite as strong yet as it is on the pitching side. Look at the top pitchers by Stuff+, an advanced pitching metric that looks at pitch shape, spin, and velocity, and you get a list of really great pitchers. Look at the top bat speeds in the big leagues, and you’ll inevitably get to a surprise — and once you add in swing shape, you might scratch your head.

“If bat speed alone was an absolute measure of success, then the top bat speeds would all be the top hitters in baseball,” Doug Latta of popular training facility The Ball Yard said.

One general manager, who was given anonymity so he could frankly discuss internal metrics, once told The Athletic a couple of years ago that his analytics team had produced bat path grades, but he didn’t quite trust them. We checked in with him again.

“They’re getting better all the time, but they’re noisier than Stuff grades still,” he said.

Ochart agreed that hitting isn’t as easy as focusing all developmental resources to move a key performance indicator or two.

“Hitting is so dynamic, and by having access to the biomechanics of all the world’s best hitters, you learn pretty quickly that there’s no one magic pattern that we should be striving for. And there’s just a lot of variance on the swing-to-swing basis between the single player and a population of players,” he said.

“So it’s not as simple as it is in pitching, where you’re just manipulating an object. You’re not reacting, so (with) hitting, the problems are a lot harder to solve from a biomechanics standpoint. I think we have some pretty good ideas on what helps contribute to speed and what contributes to bat path. Those two things are how we’ve been able to move the needle with a lot of our players.”

Advertisement

The new data: “It’s what I dreamed about 10 years ago”

We’ve tracked pitch velocity since 2007. A year later, we had decent pitch movement numbers. Seven years later, we got spin rates from the addition of Trackman. In 2020, we went to an optical system called Hawkeye and added more granular information about how a pitch moved and spun through the air. Pitch development has taken leaps and lurches forward at each of those inflection points.

The good stuff for hitters really only started in 2015, when Trackman was able to record exit velocities and launch angles. That put a premium on the ability to hit the ball hard in the air and (possibly) started the launch angle revolution. Now we’re in the middle of a big lurch forward in hitting data, as Hawkeye is giving us bat speed, bat angles, contact point, stance information — and that’s just what’s public. Teams have been privately working on linking the biomechanics information these systems provide to outcomes for four years.

Multiple coaches privately pointed to this data lag as a reason why hitting has been behind pitching so far in this rich data environment. Publicly, even as they praise the new data, they’ll point out that what happens at the plate matters the most.

“We get all our players through the lab,” said Ochart. “We get data on guys before we draft them, and it’s been a tremendous help.”

Ochart still thinks what they see on the field should direct everything, from how to determine individual plans for players to practice drills that lead players to desirable outcomes for the team and its players.

“But the biomechanics have definitely helped move the needle,” Ochart said. “And it’s helped us identify swing traits that we know lead to success.”

“As long as this game is about holding the bat and the ball coming in and matching angles, we’re always just making sure if we’re going to make an adjustment (to) any part of the body or angles or setups, that it’s because we’re trying to influence the path,” said Rangers offensive coordinator Donnie Ecker.

Advertisement

The practice environment looks different these days. Each swing is tracked by a sensor that the hitters wear on their bodies, as well as sensors in the bat. Balls in play are tracked for immediate feedback: not only launch angle and exit velocity but also batted-ball spin. The angles of hitters’ limbs are also tracked to help them sequence correctly. Players use all sorts of different practice bats and balls to mix it up and challenge themselves. Virtual reality is making inroads, but high-tech pitching machines that mimic the spin, movement and release points of major-league pitchers are everywhere. There are water bags — like the ones Paul Skenes uses for pitching! — that help players refine good acceleration and deceleration behaviors.

Improve Your Sequencing and Rotational Force with Waterbags?!?🌊 🤯

Click the link below for daily hitting/pitching programming with waterbags included 🔗 ⬇️https://t.co/PqihVu2xgD#the108way pic.twitter.com/hTV37KiO8j

— 108 Performance (@108_Performance) April 11, 2025

But the work of a good coach is still the same.

“Analytical work has something to add,” said Mejdal. “It’s gonna be counterintuitive. If it wasn’t, it already would be done. So you’re often selling change. Not only that, you’re selling counterintuitive change, and you’re selling it to someone who doesn’t have experience with someone outside of their fraternity. But it’s been a lot different now than it was 20 years ago. Because these players have grown up with it, the players are more interested and open to all this.”

“The machines, the amount of information we can collect on players from an evaluative standpoint, in training, the way we can track progress and give feedback to players, it’s what I dreamed about 10 years ago when I started,” said Ochart. “It’s an amazing environment for players to come in and get better at scale. The way I think about hitting and skill development in general hasn’t changed, but the tools have changed.”

This mirrors some of what the industry underwent with pitching 10 years ago. The data and the tech came first, and then the best communicators found ways to help players use those tools effectively.

Making it fun for the players

It was March, and it was madness — but this was the Red Sox version. More than 40 hitters competed against each other, trying to outdo each other in drills, and checking the results every day on a posted leaderboard.

“We pretty much played every day,” said Campbell, a rookie second baseman, this spring. “Whether it was who can hit the ball harder or who can hit more home runs, just different challenges. And I did manage to get to the final four.”

Advertisement

“I made it to the finals,” said Marcelo Mayer, Boston’s top infield prospect. “It was fun, and it made going to the cage exciting. One of the rounds was just who could score more runs off the Trajekt, the angle machine, or going back side, things like that.”

That’s the fun part, but the everyday is not so bad either.

“The workouts were pretty different every day,” said Campbell. “It’s not all bat speed. There’s drills that go with it, but bat speed is just picking up those heavy or light bats and swinging them as fast as possible. But past that, there are other drills we do without heavy bats that help you hit the ball in the air with your normal bat.”

The gamification — along with the key performance indicators, the data — is important, along with continuing to challenge themselves as hitters.

“You can see how you’re getting better at it each day,” said Campbell. “I had the normal bats and was swinging really hard, trying to get the soft ball in the air. Now this year, instead of an actual baseball bat, it’s a skinny one as big as my arm, and you’ve got to do the same thing but with a smaller area for misses. So everything like that gets harder and the environment gets tougher and tougher. But it helps me so when I get my normal bat back in my hand with a real baseball, it becomes easier.”

A pitching coach, who requested anonymity so he could speak about a former pitcher he coached, once said he used a 12-pack of Natty Light to incentivize a pitcher to get 13 inches of arm-side run on his sinker. While talking about players, training, and fun with a hitting coach, he admitted he was about to set up a drill that somehow linked hitting to beer pong. The new hitting data, and its gamification, is a way to make hitting drills fun in a way that pitchers — forever looking back at the radar gun after a pitch — have known for decades.

Making it fun is important. But getting better is the point.

Advertisement

“Fun to me is being really f—ing good in the game,” said Ecker. “To me, if I told Corey Seager, ‘Go have fun,’ he’d look at me like, ‘What the hell are you talking about. We got to get to work.’ And it’s actually an extreme amount of paranoia and respect from 2 o’clock to 6 that gets us ready.”

How bat designers can play a role

The torpedo bats were just one of the many innovations made to the bat in recent years. There was the hockey puck at the bottom and the axe-handle bats. What other innovations could be on the way? Now that new data allows us to know exactly where on the bat the hitter makes contact most, the possibilities seem endless.

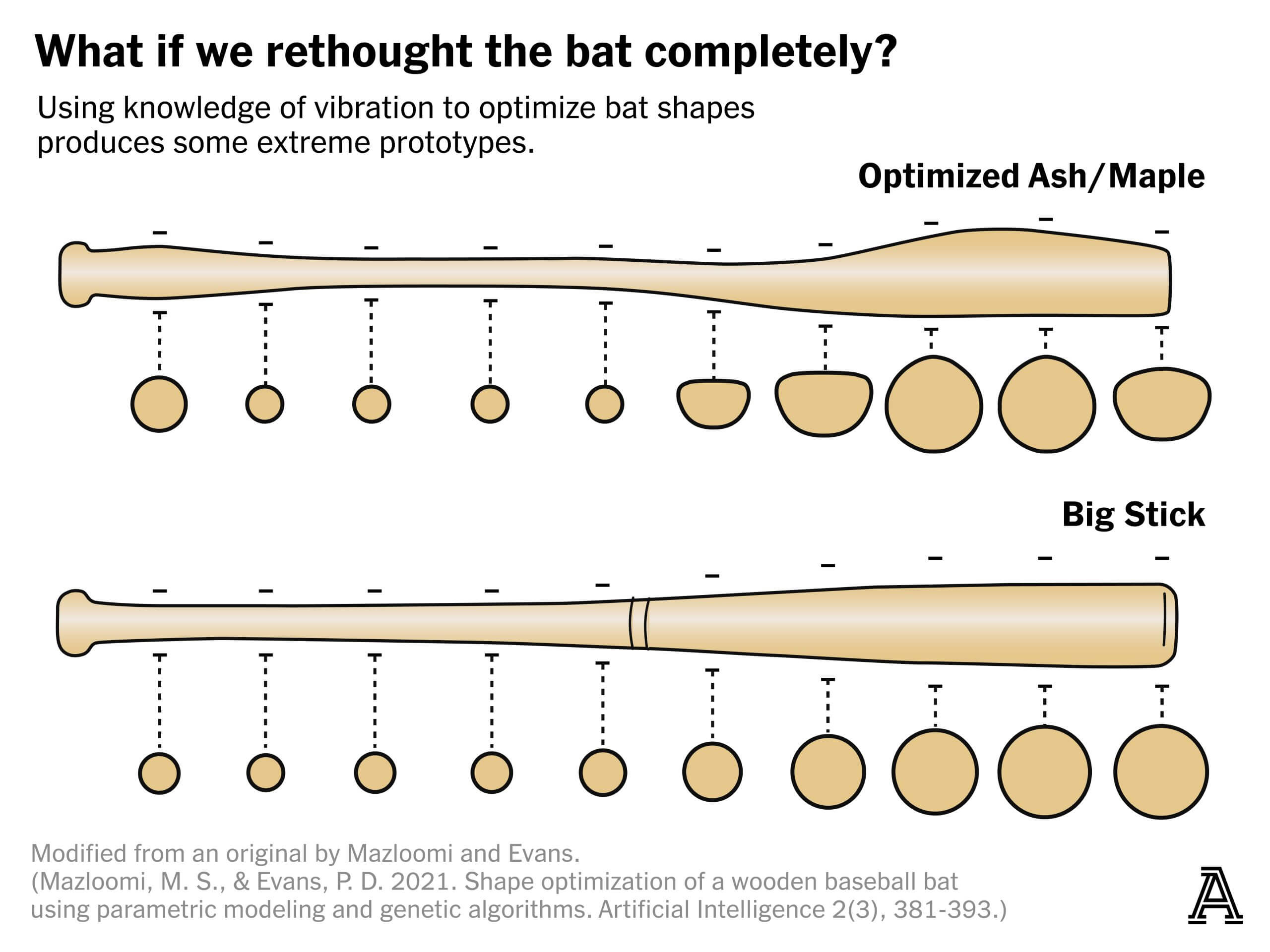

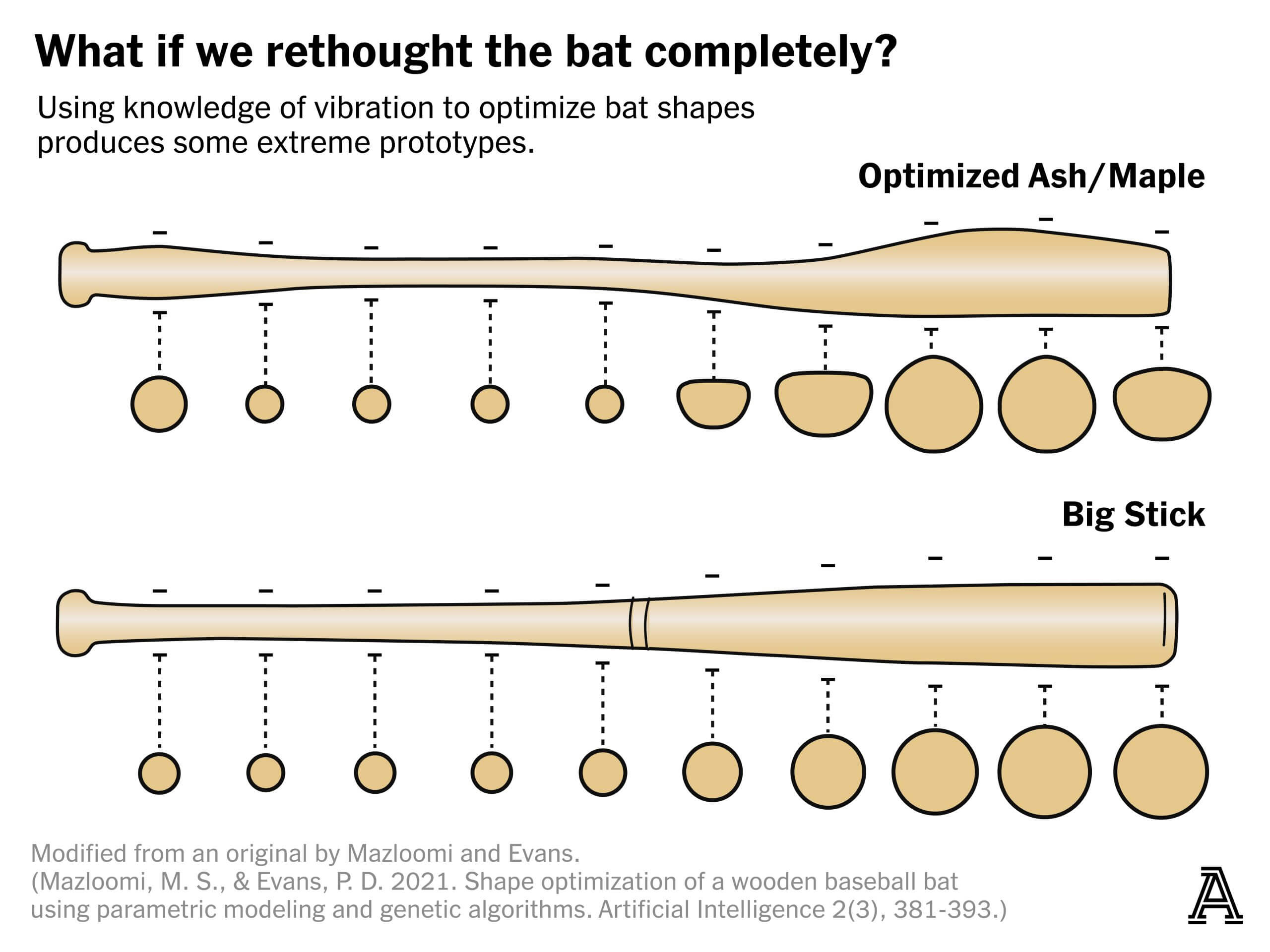

That was what Philip Evans and his graduate student Sadegh Mazloomi wondered at the University of British Columbia. The torpedo bat was about moving the sweet spot to where the hitter made the most contact. Their study was about making the most of the sweet spot by moving mass around on the bat. Look at some of the shapes they came up with in their study.

And some hitters already thought the torpedo was weird!

“The visual on the torpedo bat is definitely an issue,” said Keenan Long of LongBall Labs, a bat optimization consultancy. “Players have told me that just putting it on the plate and getting ready to hit and looking at it, it takes you out of the zone. What I think a lot of players don’t know is they’re already swinging bats that are technically torpedoed as it is.”

If the torpedo is already weirding some out, these new bats might not get traction. That doesn’t mean that simply making the most out of their current bats wouldn’t be a fruitful enterprise for hitters. Long’s outfit helps batters not only understand the best bat for them, but also understand the natural variance in the bats that they order. Players could potentially have multiple bats, each optimized for a different situation. In fact, Long has already worked with a player like that.

“He was like a manager making his lineup for the game, making his own lineup of his bats, which one he was going to use against which pitcher,” said Long. “He knows how the bats have slightly different parameters,” Long said. “He knows how they affect his swing speed and his contact quality. And he’s so fine-tuned. … There’s the ‘my wrist hurts’ bat, ‘it’s the dog days’ bat, ‘it’s August’ bat, ‘so tired’ bat.”

Advertisement

While golf has been club-fitting for years, bat-fitting has taken off recently. Maybe the future holds a combination of bat fitting with some open-mindedness about what that bat might look like and how it might help them gain an edge against pitching. All to use the right hitting utensil at the right time, even if it’s not exactly the torpedo.

“My main fear with phenomenon(s) like these happening is what is best for someone else may not be what is best for you,” said Long. “The biggest variable here is not any bat metric. It’s the player swinging the bat.”

Maybe hitting is different and will always be reacting. Or maybe hitters are in the middle of catching up data-wise, and development is about to look a lot different in the next couple of years. Maybe curvy bats, water bags, high-tech pitching machines and weighted implements are signs that hitting is finally catching up.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Photos of Kristian Campbell: Nick Cammett / Diamond Images / Getty Images)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment