Last Sunday, Inter were trying to hold on to a precious point at Bologna’s Stadio Renato Dall’Ara. It would have edged them past Antonio Conte’s Napoli in the race for the scudetto.

But Riccardo Orsolini’s overhead kick altered the script and in the dying minutes, the home fans erupted as a shirtless Orsolini celebrated Bologna’s 1-0 winner. It left Inter on 71 points, level with Napoli at the top of Serie A.

Advertisement

It was a different situation from 2022 at the Dall’Ara for Inter when Ionut Radu’s mistake had cost them the title.

But it had to be Bologna who put Inter and Serie A on standby for a possible once-in-a-lifetime play-off to be crowned champions of Italy. Yet, for Italians of a certain age, it would be the second in their lifetime.

Play-offs to determine a champion are an annual staple of American sports, with a single-game decider in the NFL and MLS, and best-of-seven title series in MLB, the NBA and the NHL. But it has rarely occurred in Europe’s top five soccer leagues, where a points system is used before a set of criteria such as goal difference, head-to-head record, goals scored etc is applied.

Since Serie A’s inaugural season in 1929-30, play-offs have been used to decide relegation, promotion, European participation and — just once — the scudetto, when teams have been level on points.

But play-offs were abolished from 2005-06 and were only brought back in 2022-23 to determine the champion or the third-relegated team in case two sides were equal on points.

In the league’s entire history, Serie A has only been decided by a play-off once. This is the story of how it played out…

In the 1963-64 season, the league title was a three-horse race between Bologna, Milan and Inter.

Bologna had started the season on a mission to improve their consecutive fourth-place finishes in 1962 and 1963. Their manager, Fulvio Bernardini, who had won the title with Fiorentina in 1956, faced a daunting task.

Bernardini’s side were up against the European champions Milan and Helenio Herrera’s Grande Inter, the reigning champions.

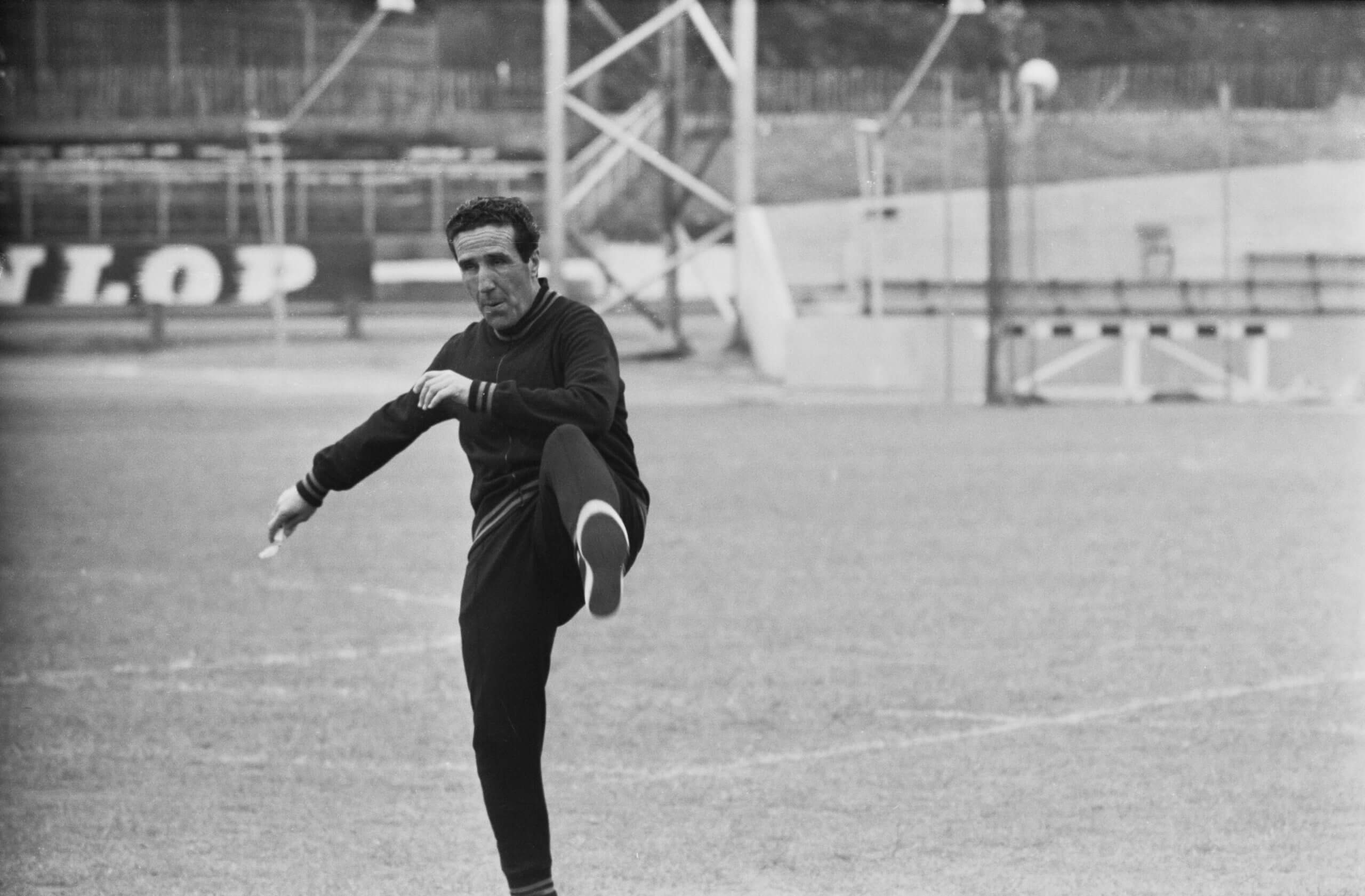

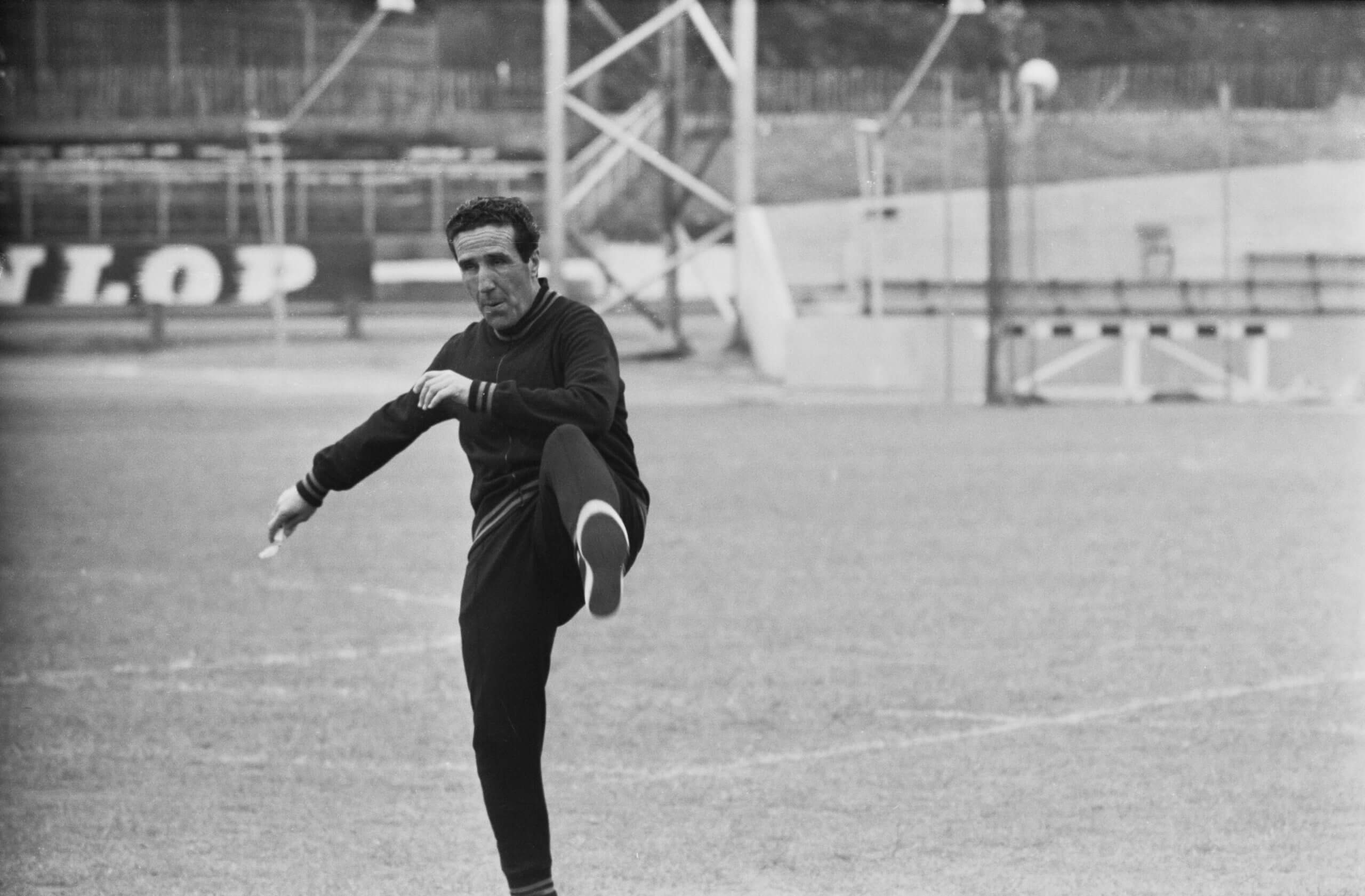

Herrera, pictured in 1965 (Norman Quicke/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Milan and Inter’s line-ups featured World Cup champions in Jair da Costa (Inter) and Jose Altafini (Milan), 1960 Ballon d’Or winner Luis Suarez (Inter), and multiple Serie A Champions. Bologna’s squad could only claim a Coppa Italia and the team’s recent Mitropa Cup.

But they had talent. Helmut Haller, Romano Fogli and Giacomo Bulgarelli would go on to win domestic and international titles. Haller, a creative attacking midfielder, and Bulgarelli, an all-rounder in the centre of the pitch, operated behind Harald Nielsen, Serie A’s top scorer the previous season.

Advertisement

Nielsen’s six goals in five games for Denmark during the 1960 Rome Olympics had caught the eye, and despite the reluctance of Bologna’s president, Renato Dall’Ara, to sign another forward with Luis Vinicio in the side, Bologna’s sporting director, Carlo Montanari, had other thoughts.

It took Nielsen a year to adapt before taking the league by storm and topping the scoring charts in 1962-63 and 1963-64 with 19 and 21 goals respectively.

Those goals were complemented by the 1963 summer acquisition of Mantova’s goalkeeper, William Negri, protecting the net behind a solid defence consisting of Carlo Furlanis, Francesco Janich and the captain, Mirko Pavinato, with Paride Tumburus sitting in front of them.

Bologna’s impressive performances under Bernardini put them neck and neck with the Milanese sides during the first half of the season, and in early February, they took the lead after Milan lost 1-0 to Lazio.

The musical chairs continued throughout February, but Bologna held on to their position at the top of Serie A. On the first of March, Haller, Nielsen and co went to San Siro to face Milan. Their 2-1 victory there solidified their status as elect champions of Italy.

However, three days later, everything was in the air.

Haller, right, with West Germany team-mate Franz Beckenbauer in 1966 (Horstmüller/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

On March 4, the Italian football federation announced that five Bologna players had tested positive for amphetamines in a drug test taken after their 4-1 victory against Torino in the previous month.

In Bologna, people took to the streets to demonstrate.

Fogli, Pavinato, Tumburus, and wingers Marino Perani and Ezio Pascutti were all under suspicion. “I have only won once in my life at San Siro, and what do you know, three days later, here’s the doping accusation,” Bulgarelli told La Repubblica in 2002.

Bologna submitted a formal request to review the second set of samples, which weren’t analysed. However, the club couldn’t take the league to court because all teams in Serie A had signed arbitration clauses, which prevented them from doing so and left them at the mercy of the sporting institution.

Advertisement

Enter three Bologna fans who were also lawyers, who submitted a complaint to the public prosecutor about how the tests were carried out.

A couple of days after the football federation’s announcement, Bologna’s public prosecutor, Domenico Bonfiglio, opened proceedings against “persons unknown” and ordered the seizure of the first and second samples.

Meanwhile, Bologna narrowly beat Sampdoria 1-0 through a Haller penalty kick, but on March 20, the punishment was announced. Bologna took a three-point hit — the match against Torino was declared as a 2-0 defeat and an additional one-point penalty was given.

Bernardini was banned for 18 months and the team’s doctor was prohibited from any sporting activity. However, the five players were acquitted on the basis that they had been drugged without their knowledge.

Bologna’s next match was away at the Olimpico against Roma, on the same day as the Milan derby, which meant Bernardini’s side had an opportunity to reduce the three-point gap between themselves and Inter, who were topping the league with 38 points — teams were still awarded two points for a win before Serie A instated the three-points system in 1994.

The Milanese sides drew 1-1 at San Siro and another Haller penalty brought Bologna two points, but the biggest story in the capital was that Bernardini was using a walkie-talkie from the stands to communicate with the bench until it was confiscated.

Next, Inter had to travel to Stadio Comunale, the then-name of Bologna’s home ground. Goals from Mario Corso and Jair guided Inter to a 2-1 victory, which widened the gap at the top of the table to four points.

Then, during April, Bernardini’s team matched Inter’s results with victories against Vicenza, Bari and Catania, in addition to winning their game in hand against SPAL. The following month, the sky turned upside down again.

Advertisement

In May, the results from the second set of samples were made public: they were clean. The tubes of the A samples weren’t well preserved and contained high doses of amphetamine that could have killed a horse.

On May 16, the federal court of appeal overturned the indictment — Bernardini was back on the bench, the doctor returned, and Bologna regained three points, which tied them at the top with Inter on 49 points.

A draw and two wins for both sides in the last three games meant Bologna and Inter finished on 54 points, but for a brief moment, Stadio Comunale erupted, thinking Bologna had won the title.

“Spareggio con l’Inter” belted out the stadium’s speakers after Bologna’s 1-0 victory against Lazio, but it was wrongly heard as “Pareggio dell’Inter”.

A one-letter difference, which is enough to win you the title because ‘Pareggio dell’Inter’ means Herrera’s side had drawn with Atalanta in the other game and Bologna were champions. Meanwhile, ‘Spareggio con l’Inter’ is a play-off with Inter, which was the case because they had in fact beaten Atalanta 2-1 at San Siro.

For the first and only time in Serie A history, a play-off would decide the champions of Italy.

Bologna, pictured in 1964 (Mondadori via Getty Images)

Four days before the match, Bologna were struck by terrible news.

In a meeting between Inter, Bologna and the league’s presidents to discuss revenue from the play-off, Dall’Ara collapsed with a heart attack and died in Inter owner Angelo Moratti’s arms.

Bologna’s players heard the news while preparing for the match at Lazio’s training ground in Tor di Quinto, in the north of Rome. Bernardini had taken his side to Fregenae, a beach town to the west of the city, to go in ‘ritiro’ — a standard practice in Italy, with the players spending the days or week before the game at a hotel or training facility.

There were different reactions to Dall’Ara’s death, with some saying the team shouldn’t play. “I was hoping they would postpone the game,” Janich, Bologna’s defender, told the club’s official channel 50 years later.

Advertisement

The football federation and clubs decided to proceed with the match, and as Bologna’s striker Nielsen later explained, the death of Dall’Ara inspired the team.

On June 7, 1964, Bologna and Inter faced each other at the Olimpico in Rome. The stadium was full, with fans climbing trees on a hill overlooking it.

In the build-up, Pascutti’s injury was a dilemma for Bernardini. The winger was an important attacking solution down the left side, but the Rome-born manager had an unorthodox solution.

Bologna fans hold a banner for Ezio Pascutti after his death in 2017 (Mario Carlini / Iguana Press/Getty Images)

Bernardini used Bruno Capra, a full-back, on the right side behind winger Perani to nullify Inter’s left side and Giacinto Facchetti’s attacking runs from left-back.

The tweak meant Bologna’s left side of their attack was vacant and occupied by roaming players — even Perani moved there, knowing Capra was in position to defend the right wing.

The first half of the match was uneventful, with Nielsen the closest to scoring.

Early in the second half, Facchetti struck the ball from outside the penalty area, but his shot was saved by Bologna goalkeeper Negri.

Inter weren’t able to break down Bernardini’s defence and, from a counter-attack, Bologna got close again. Fogli’s shot from outside the penalty area was saved by Inter’s goalkeeper, Giuliano Sarti, who jumped quickly to deny Nielsen on the rebound.

Inter’s best chance came in the 62nd minute when Suarez dribbled through Bologna’s midfield and combined with Sandro Mazzola to find Aurelio Milani free in the penalty area, but the striker’s shot missed the target.

With 16 minutes to go, Armando Picchi fouled Haller near the edge of the penalty area and from that free kick, Bulgarelli set up Fogli, whose shot deflected off Facchetti and hit the back of the net to give Bologna the lead.

It wouldn’t be a Bologna victory without a goal from Nielsen, though. In the 82nd minute, Fogli found Nielsen’s run behind the Inter defence and the Denmark striker scored past Sarti to win Bologna their seventh (and most recent) Serie A title.

In a moment of vindication, the Bologna players carried their manager, Bernardini, over their shoulders as they celebrated a hard-fought scudetto. The Bologna players couldn’t believe that they were the champions of Italy.

Fast forward 61 years and nothing separates Inter and Napoli with only five games to play.

Inzaghi’s side have on paper the tougher run as they host Roma and Lazio at San Siro. In addition, Napoli don’t have any European commitments, unlike Inter, whose semi-final encounter against Barcelona has been affected by Serie A’s decision to move their match against Roma to Sunday to accommodate Pope Francis’ funeral.

If Napoli and Inter match each other’s results until the end of the season, it’s possible the title play-off could take place at the Olimpico once again.

Indeed, as in 1964, it might be that all roads lead to Rome.

(Top photo: Marco Luzzani/Getty Images; design: Eamonn Dalton)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment