LOUISVILLE, Ky. — Bob Baffert is a fan of the film “No Country for Old Men.” “Oh, it’s a great movie,’’ the famed trainer tells The Athletic. “You gotta watch it.’’ The movie comes up, as things often do with Baffert, as he winds his way through a thought process. Baffert isn’t a rambler, but he’s a weaver, often zigzagging his way through a story to make a point. In this case, he is searching for a way to explain how he feels about the end of his three-year suspension and return to the Kentucky Derby.

Advertisement

He is trying to convey that he’s happy it’s over and more, that he’s not terribly interested in rehashing what happened, why it happened and how it all went down. He has, however, rendered his own attempts at explanation inadequate, turning instead to the Coen brothers for assistance. “There’s a line in ‘No Country for Old Men,’” Baffert says. “An old guy gets shot, a cowboy like me.’’

In the movie, Ellis, a retired sheriff’s deputy, is in a wheelchair after being shot in the line of duty. But the line Baffert steals is delivered after Ellis is asked what he would do if the man who shot him were to be released from prison. From memory, Baffert quotes Ellis’ answer nearly word for word. “Well, all the time you spend trying to get back what’s been took from you, more is going out the door. After a while, you just have to try to get a tourniquet on it.’’

Baffert then contributes his own addendum: “That’s how I feel about all of this. It’s time for the tourniquet.’’

That is always the hope of a public figure caught in the midst of some mayhem. When said mayhem is settled, everyone will simply carry on like it never happened.

In some regards, Baffert will get his wish. On the backside of Churchill Downs this week, Baffert walks around just as he has for decades, sunglasses on, hands shoved in his jeans pockets. Onlookers and media gather at Barn 33, the corner of Churchill property that Baffert has long called home, and where his Derby hopefuls, Citizen Bull and Rodriguez, rest after a morning exercise. The outside wall of the barn, barren for the past three Derbys, is full again. The plaques signifying Baffert’s accomplishments, remounted.

And the one detailing his six Derby winners — from Silver Charm in 1997 to Authentic in 2020 — bears no mention of Medina Spirit, the horse that earned him his exile. It is, indeed, like it never happened.

Except it did, which bears the simple question: What now?

Twenty-nine years ago, Baffert stepped to a ready-made lectern outside of Barn 33, rapped on the microphone and quipped, “Attention. Attention. Everything’s cool.’’

In 1996, Baffert’s horse, Cavonnier, shared barn space with Unbridled’s Song, the favorite in the Derby that year, a horse that drew so much attention that the bemused and largely ignored Baffert decided to make a joke out of it.

Advertisement

Baffert was the new kid on the block, the irreverent breath of fresh air there to upend the stranglehold seasoned trainers D. Wayne Lukas and Nick Zito had on the Derby. Upon winning a big race on Halloween, Baffert wore a pumpkin mask into the winner’s circle and at the Derby zinged one-liners like a comedian. Cavonnier was his first Derby entrant, and for a split second, the trainer thought he went one for one. Instead, after an agonizing review, the photo on the board revealed Grindstone, trained by Lukas, as the winner by a nose.

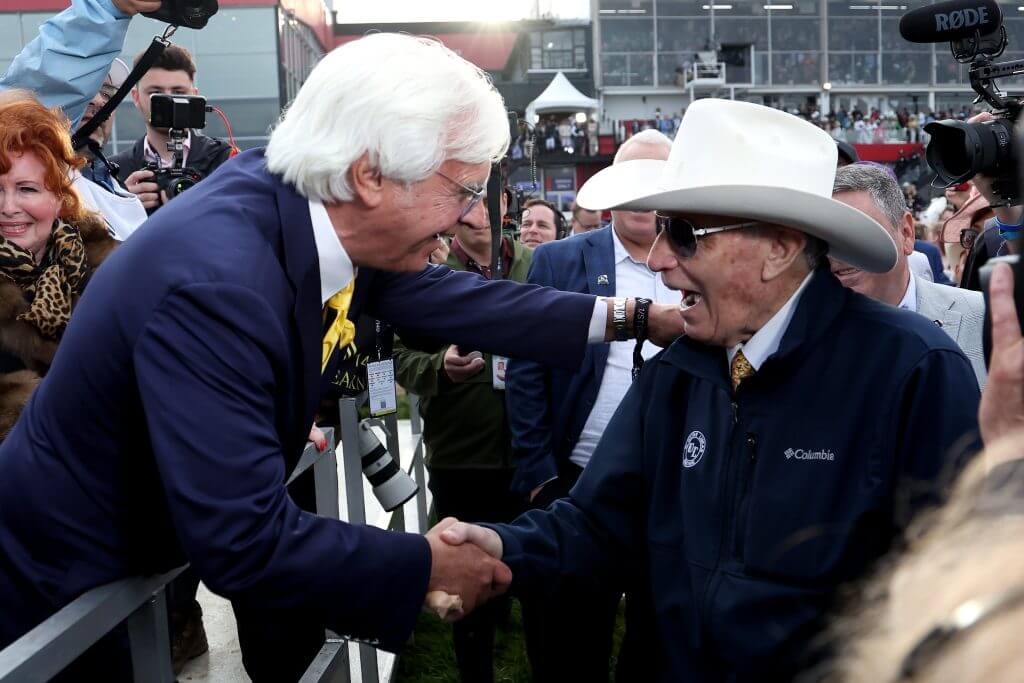

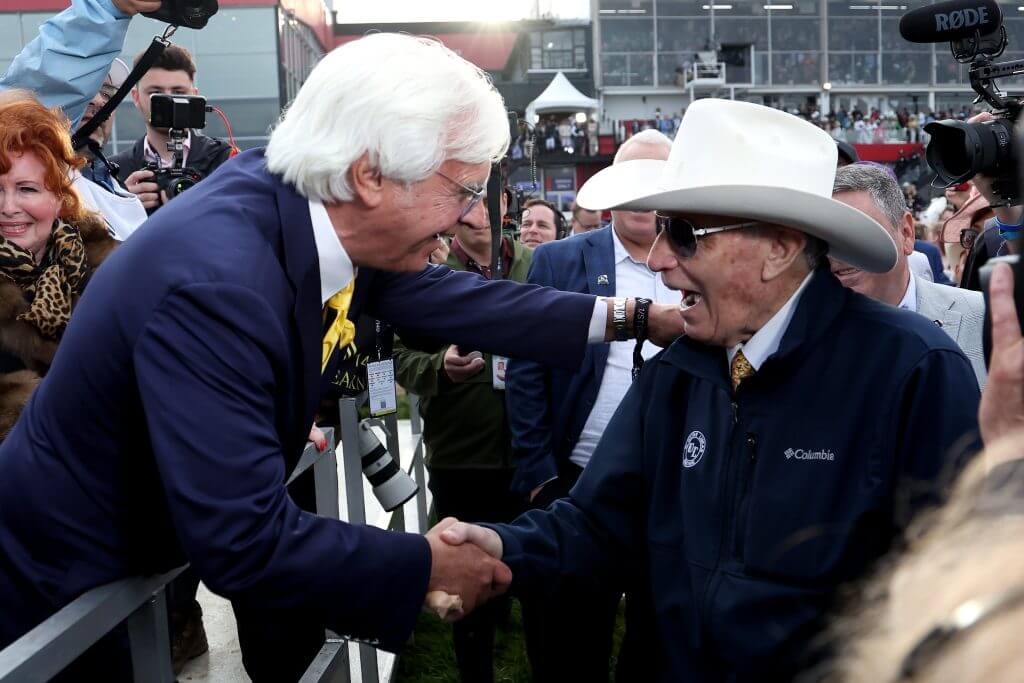

Bob Baffert (L) congratulates D. Wayne Lukas after his horse won the 149th running of the Preakness Stakes at Pimlico Race Course on May 18, 2024. (Photo: Rob Carr / Getty Images)

But the following year, Silver Charm gave Baffert his first Derby winner, and the trainer danced around the winner’s circle with his trophy. Silver Charm also won the Preakness and narrowly lost a shot to break the then-19-year-old Triple Crown hex at the Belmont, losing in the stretch to Touch Gold. That made Baffert a pretty big deal. But when, in 1998, Real Quiet gave Baffert another Derby winner, won the Preakness and lost the Belmont by a nose, Barn 33 became the place to visit on the Triple Crown trail.

For the next two decades, Baffert and the Derby became nearly interchangeable. Baffert would win again in 2002 with long shot War Emblem, and finally deliver horse racing its moment in 2015, when American Pharoah finally won the Triple Crown. Three years later, he notched his second Triple Crown with Justify, solidifying his place in history.

In a sport where the athletes don’t talk, Baffert’s combination of success, accessibility, affability and (thanks to that shock of white hair) recognizability made him the de facto ringleader of horse racing. He played his part gamely. Despite his growing pocketbook and stature, he remained the quotable, affable storyteller. When Pharoah prepped for the Breeders’ Cup on the heels of winning the Triple Crown, Baffert waxed eloquent about his first trip to the race, back when he couldn’t afford a good shirt. Between the crummy fabric and lack of undershirt, Baffert spent the day warding off a serious case of chafed, bleeding nipples.

But nowhere did he hold court better than at Churchill and the Derby, the crown jewel of horse racing. It is fair to say each made the other some money. Baffert’s Derby wins brought him better horses — Real Quiet ran owner Mike Pegram $17,000 at his yearling sale, while Citizen Bull came with a $675,000 price tag — which in turn brought him better odds and eventually more prize money. Meanwhile, his successes improved the allure of horse racing, especially after Pharoah’s Triple Crown, and helped turn the Derby into an even bigger bucket-list item.

Advertisement

In 2015, the average Kentucky Derby ticket price on the secondary market ran $877. Post Pharoah, it soared to more than $1,200. After Churchill underwent a massive renovation in time for last year’s 150th running of the roses — carving out new exclusive clubs and access points, plus a two-story paddock — fans paid on average $1,651 on the secondary market.

Yet beneath the business partnership, Baffert’s affinity for and appreciation of the Kentucky Derby were genuine and ran the arc of his career. He won the big one when his parents, Bill and Ellie, were still alive and watched on TV back in Nogales, Arizona; won it with his first wife, Sherry, and his second wife, Jill. Took second with a horse, Bodemeister, named after his youngest son, Bode, when the boy was just 7, and won the race when the boy grew into a teenager in 2020.

“That place is magical. It truly is,’’ Baffert says. “I think all every trainer wants is, when your horse makes that final turn at the Derby, is to have a reason to scream. That’s all anyone wants. To have a reason to hope.’’

Like the end of any long marriage, then, the divorce between Baffert and Churchill was messy.

The not-so-short synopsis of the protracted events is this: One week after he crossed the finish line first at the 2021 Kentucky Derby, Baffert’s Medina Spirit tested positive for betamethasone, an anti-inflammatory that is permissible for therapeutic use in horses, but must be out of their system to pass post-race testing. A month later, and after a split sample also returned positive, Churchill Downs Incorporated suspended Baffert for two years.

Medina Spirit, ridden by jockey John Velazquez, crosses the finish line to win the 147th running of the Kentucky Derby on May 01, 2021. (Photo: Tim Nwachukwu / Getty Images)

In February 2022, a full nine months after he crossed the finish line and two months after he collapsed and died after training at Santa Anita, Medina Spirit was officially stripped of his Derby victory. Baffert filed a lawsuit that month and continued to fight, arguing he had done nothing wrong. In response, Churchill Downs said that because Baffert continued to “peddle a false narrative” about the horse’s DQ, it would extend his suspension for a third year, through last year’s 150th run for the roses.

Three Derbies came and went without Baffert. He watched the first one with clients in Arizona, finding himself shouting the same thing as most people on hand at the race in 2022, when 80-1 Rich Strike crossed first.

Advertisement

“I yelled, ‘Rich Strike? Who is Rich Strike?’” Baffert laughed.

He took in the second in the semi-anonymity of Rillito Park, a quarterhorse track where he started his career as a jockey and then a trainer decades ago. Last year, he hosted a small Derby party in California. Every now and again since 2021, he would be in an airport or somewhere in public when an unknowing fan would shout, “Bob, who you got in the Derby this year?” He’d just smile in response. He admits to feeling some pangs but stops short of calling it full-on FOMO.

“If I had a horse like American Pharoah, then it would be FOMO,’’ he says. “You miss it because you know what it’s like to be there, in front of 150,000 people, but you can’t be there. What can you do?”

By 2024, both Baffert and Medina Spirit owner Amr Zedan lost their steam to keep fighting. Zedan called his trainer and gave his blessing to drop the lawsuits and erase the line in the sand. In January, they asked the Kentucky courts to dismiss their case with prejudice, meaning it could not be reopened. “I knew once I dropped everything, we could end this thing,’’ Baffert says. “So I reached out to Churchill.’’

In July 2024, it finally ended. Baffert issued a statement taking full responsibility for the positive test involving Medina Spirit. Shortly thereafter, Churchill Downs rescinded its suspension. “All parties agree that it is time to bring this chapter to a close and focus on the future,” Churchill Downs Inc. CEO Bill Carstanjen said in the statement.

Technically, his return to the Derby is not Baffert’s first time back to Churchill. On November 27 of last year, his horse, Barnes, won the seventh race of the day, sending Baffert back to the very familiar winners’ circle. Carstanjen was among those who gave him a victory hug.

But the seventh race on a late Wednesday in November is not quite the same as the call to the post on the first Saturday in May. Along with the sport’s aficionados, the casual observer pays attention to the Kentucky Derby. How fans, both casual and devoted, will consider Baffert now is a legitimate question. He is at once inarguably one of horse racing’s most accomplished figures and a litmus test for the appetite for the sport.

Advertisement

“He broke the rules, but he wasn’t trying to cheat,’’ says Doug O’Neill, the two-time Derby-winning trainer, who himself has been suspended for multiple positive tests. “It’s confusing because it’s a therapeutic medication. He’s allowed to use it. It just can’t be in the horse’s system.

“But I do think it’s important that Churchill treated him like anybody else. He’s the biggest name in horse racing, and he broke a rule. That’s a credit to them. They called it. …But he also paid his dues, and he should be welcomed back like anyone else.’’

The complexities of Baffert’s case are part of the problem. A horse tests positive, and people automatically label it a doping violation. It’s simply not accurate. Both Medina Spirit and Gamine, a filly who was disqualified from the Kentucky Oaks after testing positive for the same anti-inflammatory as Medina Spirit, were guilty of medication overages. That is a fine but critical line, says Lisa Lazarus, the CEO of the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA).

An outgrowth of the federal government’s Horseracing Safety and Integrity Act, HISA has brought order to what had been a disastrously disorganized governance structure. Prior to HISA, there were neither centralized testing protocols nor penalties in place. The organization has revamped the entire process, along with monitoring jockey and track safety, by harmonizing the testing procedures, automating the process (yes, they used paper up until recently) and even eliminating some testing sites that didn’t meet their standards.

HISA was not in effect when Medina Spirit’s case began and had no jurisdiction over Baffert’s penalties, but Lazarus is quick to point out the discrepancy in how Baffert has been labeled and what he actually did.

“It is not doping,’’ she says. “It is a medication overage, and under HISA, a first-time offender would only pay a fine.’’

To the cynics who can’t imagine Baffert not knowing what went into his horse, Lazarus laid out a plausible scenario, explaining that, unlike human athletes, horses aren’t even allowed to have aspirin or ibuprofen in their system for races but that both, along with the anti-inflammatories used for Medina Spirit, are often given as care between races. A careless mistake of not properly calculating the time between races, or giving wiggle room for a horse’s metabolism, could make Medina Spirit positive. He tested for 21 picograms (a picogram is one trillionth of a gram).

Advertisement

“I also will say that Bob Baffert is one of the few high-profile trainers who has not had a blip under the HISA rules,’’ Lazarus says. “No overages, nothing. He has done an excellent job following the rules.’’

The trouble is, long before Baffert, the majesty and elegance of the animals has existed uncomfortably next to the stark reality that so many have been mistreated in the name of sport. Protestors are so normal as to be expected on a race day: people arguing against the inhumanity of horse racing standing outside the gates of Churchill, shoulder to shoulder with the proselytizers trying to convince people to turn back from gambling and debauchery to save themselves.

From drugs to mask pain to jockeys using buzzers to encourage speed, humans have invented all sorts of ways to make a horse run faster. In 2020, the FBI indicted 27 people, a combination of trainers, veterinarians and drug suppliers, for offenses including using cobra venom as a painkiller. More than 50 years before Medina Spirit’s DQ, Dancer’s Image was similarly removed as the Derby winner after testing positive for phenylbutazone, another anti-inflammatory.

Countless trainers have been suspended over the years, including many of the biggest names in the sport. Zito vigorously fought New York racing regulators over a suspension in 2003 before dropping his fight, and in 1999, Churchill dinged four-time Derby winner Lukas for 10 days after one of his horses tested positive.

Thirteen years later, the famed Lukas took public umbrage at O’Neill and Richard Dutrow, who faced suspensions after winning the Derby, for publicly embarrassing the sport.

“You are good enough. You’re talented. You’ve got good clients. You’re dealing with good horses,’’ he said. “You can do it the right way, and it will work for you. You don’t need to push the envelope.’’

Of Baffert’s return to Churchill Downs, though, Lukas told reporters this week, “He belongs here. He’s the face of [the Derby]. I said that for three years, and every year since. That [suspension] was wrong. That was wrong. I can see their side, too. But we’re glad to have him back.”

Bob Baffert at Churchill Downs on April 28, 2025. (Photo: Andy Lyons / Getty Images)

As Lukas states, Baffert is the biggest of big names. Had Medina Spirit’s win stood, Baffert would have become the all-time winningest Kentucky Derby trainer, with seven victories in Louisville. (As it is, he remains tied with Ben Jones, whose last win came in 1952.). His infractions came at a time when horse racing was trying to solve its image problem.

Advertisement

“Bob became to some extent representative of the things that had gone wrong, fairly or unfairly,’’ Lazarus says. “But it’s not doping.’’

That all made the punishment more newsworthy, and now makes his return to the track more than just another day on the backside. Sports have long had a complicated relationship with repentant sinners and those in search of a second chance. Some are granted absolution without a second thought; others are left to live in the purgatory of public judgment.

Neither Citizen Bull nor Rodriquez will go off as the favorite on Saturday, but both are good enough to win. Rodriguez won the Grade 2 Wood Memorial and enters the Derby fourth on the points leaderboard. Citizen Bull won the American Pharoah Stakes and Breeders Cup Juvenile as a 2-year-old, and finished fourth this year at the Santa Anita Derby.

And anyone who pays a lick of attention to horse racing knows that a Baffert horse is never really a bad bet.

“I know people will still have opinions, and there’s nothing I can do about that,’’ Baffert says. “People will say what they say or think what they think. I know it was an honest mistake, but at the end of the day, it couldn’t be in the horse’s system. That’s the rule, and Churchill had to do what they had to do. I respect that. I’m grateful to be back. I love this race. I just want to move forward.’’

The tourniquet has been tied. Time will tell if Baffert can stop the bleeding.

(Top Illustration: Eamonn Dalton / The Athletic; Photo: Al Bello / Getty Images)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment