Of the thousands of college basketball players who entered the transfer portal this spring, at least 137 of them stand out because of one thing they’re all lacking: remaining college eligibility.

Take star College of Charleston center Ante Brzovic, for example. The Croatian-born big man moved to America in 2020 and enrolled at Division II Southeastern Oklahoma State University. He redshirted his first season when he wasn’t academically eligible because he barely spoke English. He then played in 28 games the following season before transferring to Charleston, where he became a three-year starter and first-team all-conference honoree. That’s four full seasons of NCAA competition — which, under conventional rules, would normally mean Brzovic is out of eligibility.

Advertisement

Instead? Brzovic and his legal team are suing the NCAA for another season of eligibility, after his initial waiver request was denied on April 1. While the case is unlikely to be fully adjudicated before next season, all Brzovic needs to suit up come November is for a judge to grant a temporary restraining order (TRO).

Brzovic’s situation is unique, but his larger strategy — hoping the courts offer relief — is not. More than 10 eligibility lawsuits have been filed against the NCAA since Jan. 1. Other athletes are appealing to the NCAA. Minnesota forward Dawson Garcia averaged a career-best 19.2 points per game last season and is seeking a waiver for his sophomore season, when he left North Carolina early to be closer to family dealing with medical issues. Saint Louis guard Isaiah Swope played his freshman season in DII and, like Brzovic, is seeking another season accordingly. Both Garcia and Swope — and Brzovic, who has drawn interest from high-major programs this offseason, according to his legal team — have the potential to be difference-makers next season, which is why coaches have continued recruiting these players despite their uncertain outcomes.

Now, that’s not to say that all 137 such players are the same. Clemson starters Ian Schieffelin and Jaeden Zackery, for example, both have played four full DI seasons and said on social media they entered the portal only at the advice of their representation — just in case the NCAA loosens its restrictions.

While I am pursing my options on the professional level I have been advised, due to pending NCAA cases, to enter the portal on the very outside chance more eligibility is allowed.

— Ian Schieffelin (@ian_schieffelin) April 21, 2025

But if there’s one thing that most players seeking extra eligibility have in common, it’s the possibility of a hefty payday. Brzovic’s legal team has argued that he stands to earn at least $1 million in NIL next season if deemed eligible, for example. That claim also hits at the general idea tying many of these legal challenges together: Eligibility limits could violate antitrust laws.

Advertisement

“Any rule that limits how long they can play,” said college sports lawyer Mit Winter, “is hurting them economically.”

That’s especially true because there has never been more money in college basketball — in part because of the pending House v. NCAA settlement, which will allow schools to pay players directly for the first time. Potential All-Americans, like Texas Tech forward JT Toppin, stand to make over $3 million next season alone. The going rate for all-conference players, or elite five-star recruits, is easily north of $2 million, according to multiple high-major coaches and general managers who spoke with The Athletic. Even average high-major starters are often looking at seven-figure deals.

Comparatively, the starting point for most G League and overseas contracts is in the five figures.

Though the NCAA has granted several blanket eligibility waivers lately — as it did after the COVID-19 pandemic, for anyone who played during the 2020-21 season — that isn’t usually the governing body’s first option.

Instead, it often takes legal recourse to force the NCAA’s hand. Vanderbilt quarterback Diego Pavia won an injunction against the NCAA in December, which allowed him to recoup a year of DI eligibility for the time he’d spent in junior college. Then the NCAA, while appealing the ruling, granted another blanket waiver — this time, for any players whose eligibility was set to expire in 2024-2025 and who had “competed at a non-NCAA school for one or more years.”

“Candidly,” said Mark Peper, Brzovic’s South Carolina-based lawyer, “I would love for this to open the floodgates.”

Still, the NCAA has not lost all of its eligibility challenges. A Tennessee baseball player and four football players in North Carolina seeking additional eligibility were recently rebuffed in court. In a statement provided to The Athletic, Tim Buckley, the NCAA’s senior vice president of external affairs, referenced the association’s standing efforts to gain relief from lawsuits through federal legislation. “Eligibility rules ensure high school students have the same access to life changing scholarship opportunities that millions of young people had before them,” he said in part, “and only Congress can act to protect these basic rules from these shortsighted legal challenges.”

Advertisement

Could a landmark eligibility alteration be on its way? Earlier this year, the NCAA discussed the possibility of giving college athletes five full seasons of competition instead of four, regardless of situation, in an attempt to clear the system of redshirts and waivers. Some college leaders have voiced concern for possible downsides, such as fewer opportunities for high school recruits — and questioned if the change would actually stop waiver requests and legal challenges. The concept of five seasons in five years hasn’t been recommended for formal review, but it’s a conversation that could pick up again once the House settlement is finalized and would represent another seismic shift to college sports’ infrastructure.

Current NCAA rules state that college athletes have five years to complete four seasons of full competition. (The fifth year is for players who redshirt, either for development or injury reasons.)

But ever since the COVID-19 pandemic, various exceptions and court rulings have whittled away that standard “four-in-five” rule. That began with the “COVID-19 year” of eligibility that allowed stars like Hunter Dickinson, Armando Bacot and Johni Broome to play five seasons of DI ball. Then there’s the Pavia case, which will allow players like Chad Baker-Mazara — who spent a year in juco before starting for Auburn the past two seasons — to suit up again next winter. Baker-Mazara recently announced his transfer to USC.

Dreams turned into reality!! Let’s go to work!! #Committed @USC_Hoops pic.twitter.com/ymMVbtn6BI

— Chad Baker-Mazara (@ChadBaker2700) April 28, 2025

And that’s only the tip of the eligibility iceberg.

In April, Rutgers football player Jett Elad earned a temporary injunction by playing off Pavia’s ruling. Elad’s college career began in 2019, meaning his NCAA-allowed five-year window should be up. But because he spent one season redshirting, one season at junior college and got back a season for the COVID-19 year, Elad argued he had played only three countable seasons in Division I. A federal judge issued a TRO, making him eligible this fall, despite that technically being Elad’s seventh season of college football. The NCAA has appealed that ruling in another effort to defend its ability to enforce eligibility rules and has until June 6 to file its response.

“The four-year rule now is sort of arbitrary,” Winter said. “Initially, it was the thought that most people go to school for four years, but that’s not always necessarily the case anymore.”

Then there’s Brzovic, arguing his second season at Southeastern was a “lost year” because of language difficulties, mental health struggles and hardships following the pandemic — and therefore, Brzovic’s time at DII shouldn’t count against his four years of eligibility. He makes a similar argument as the one that Wisconsin cornerback Nyzier Fourqurean used to receive an injunction in February. Fourqurean’s lawsuit is still pending and is also being challenged by the NCAA, but the TRO he received means he’ll be able to suit up for the Badgers this fall.

Advertisement

Additionally, Brzovic’s legal team claims the NCAA’s rigid waiver categories no longer accurately represent the variety of players and backgrounds in DI. Atop that list is there not being any specific waiver for international players, despite them migrating en masse to the United States to play college ball (and reap the benefits of NIL).

Darren Heitner, a Florida-based NIL lawyer who is also part of Brzovic’s legal team, said he’s heard from over 50 players this offseason all wondering how they can secure additional eligibility. Of those players who have reached out, he’s presently working only with a handful whom he believes could qualify for legitimate hardship waivers. Heitner has previously worked with the NCAA on eligibility waivers.

To his point, Tennessee baseball player Alberto Osuna’s motions for additional eligibility were twice denied in court. Four former Duke and North Carolina football players were also denied after challenging the NCAA’s five-year window of eligibility.

As for those hoping for a blanket fifth season? Changes in NCAA policy may not come quickly enough.

“In my conversations with the NCAA,” Heitner said, “all I’ve been led to believe is that they’re just conversations and that there is no draft legislation yet — which means, to me, it’s very unlikely that the class of individuals who are reaching out to me now will be affected by any change in policy. It’s likely (to be) those players next year, if at all.”

That’s not to say the sport won’t include mid-20’s hoopers with various one-off situations.

After averaging 18.4 points and 8.1 rebounds last season, Brzovic could easily be a high-major starter in the winter, if he’s deemed eligible — and he’s not the only one.

Take Memphis big Dain Dainja, for instance, who reportedly filed a waiver to the NCAA last week. Dainja redshirted his freshman season at Baylor in 2020-21 — which he would get back regardless because of the COVID-19 rule — and played in only three games during the 21-22 season, before transferring to Illinois in December 2021. (He did not suit up for the Illini the second half of that season.) Dainja then played two full seasons at Illinois before ending his career at Memphis this season. Technically, because Dainja played in three games during the 2021 fall semester at Baylor, he’s already used four “full” Division I seasons. But the NCAA has shown a proclivity for granting waivers to players who appeared in under 30 percent of their team’s games in a given season, usually because of injury, which was not the case for Dainja. He turns 23 in July.

Advertisement

Or how about Baker-Mazara, who will turn 26 next January? His college career began in 2020-21 at Duquesne, although the COVID-19 year wipes that from his eligibility slate. The Dominican wing then transferred to San Diego State for the 21-22 season, before dropping down to the juco level at Northwest Florida State College in 22-23. He then transferred up to Auburn, where he spent the past two seasons and became a key cog on a Final Four team. Normally, Baker-Mazara’s year in juco would have counted against his four-year clock — but the Pavia ruling granted him another year of eligibility.

Perhaps the most remarkable one-off is former Grand Canyon wing Tyon Grant-Foster, who is in the transfer portal. The 6-foot-7 NBA prospect began his college career in juco in 2018-19 at Indian Hills Community College and spent two seasons there before transferring to Kansas. Grant-Foster was a rotation player at KU in 2020-21, before transferring to DePaul.

Then midway through DePaul’s season opener in 2021-22, Grant-Foster collapsed — and because of two heart surgeries that followed, he was unable to play the remainder of that season or the next. He was granted a medical redshirt for the 21-22 campaign, meaning, once again, Grant-Foster had yet to have a college basketball season count against his four years of eligibility. He was finally cleared to play in March 2023, at which point he transferred to Grand Canyon, where he’s spent the past two seasons as the Antelopes’ best player. Grant-Foster should have at least one more season of eligibility left, despite turning 25 in March.

“Everyone says the world’s going to end because all these players are going to have 12 years and play into their forties,” Heitner said. “That’s hyperbole.”

But that, at least in some circumstances, has been the NCAA’s viewpoint. The governing body’s response to Brzovic’s first waiver request, for instance, cited that sentiment as a slippery slope college sports could go down if eligibility mattered only at the DI level:

Plaintiff effectively seeks permission for student-athletes to compete during, at minimum, fourteen seasons of intercollegiate competition: an athlete could compete in two seasons of junior college competition, four seasons in Division III competition, four seasons in Division II competition, only then to matriculate to a Division I institution at roughly the age of twenty eight with a fresh four-season clock. The outcome would eliminate the collegiate nature of intercollegiate sports — making Division I the “professional” ranks that “student”-athletes may join after participating in the “minor leagues” of the lower Divisions.

Translation: Where does this all end?

Advertisement

“The NCAA does allow for additional years beyond the traditional four, and that’s why there is a waiver process,” Heitner said. “There’s many, many, many instances where players perform for more than four years and beyond a five-year window. So I think if you’re going to make exceptions, it just needs to be streamlined.”

But for the time being, college sports’ eligibility status is a patchwork quilt of various federal injunctions, court rulings and one-time waivers. If the House settlement is finally completed this summer, the NCAA could return to exploring the five-year plan. That wouldn’t provide relief in time for players like Brzovic, whose legal battles are ongoing.

If anything, situations like Brzovic’s have underscored the need for a long-term, stable solution.

“Five years is, I think, going to be looked at as a compromise,” said a former NCAA official, who was granted anonymity in exchange for his candor, “the more sixth- and seventh-year guys get approved to be able to stick around.”

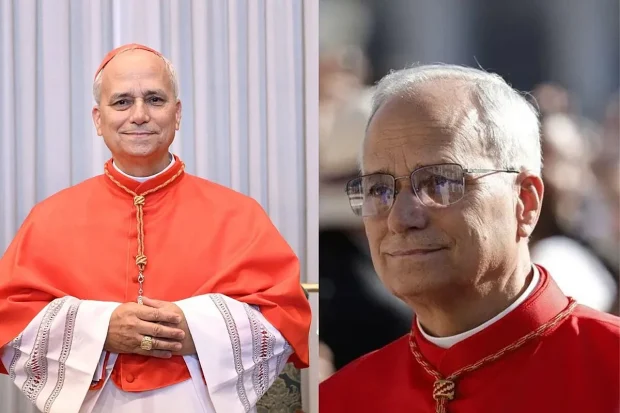

(Photo of Ante Brzovic: Ehrmann / Getty Images)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment