In a period when a small handful of superclubs regularly win the league, it can be difficult to differentiate between various title-winning campaigns. But Barcelona’s 2024-25 La Liga victory — albeit not yet mathematically certain — will live long in the memory.

There are certain elements of this Barca season that are very specific to this particular title success. They’re playing in the city’s Olympic stadium rather than the Camp Nou. They’re using a new generation of world-class teenagers, led by Lamine Yamal and Pau Cubarsi. The thrilling victory over Real Madrid on Sunday completed a clean sweep of four Clasico victories this season. But, above all else, this Barcelona side has a distinct way of playing, broadly in keeping with the club’s traditions but also more daring, more extreme, and more end-to-end than anything in recent memory.

Advertisement

Sunday’s 4-3 victory summed it up. Barcelona were clearly the better side on the day, but they also had several scares. They fell 2-0 behind. At 3-2 up, they thought they’d conceded a penalty, but were saved by a VAR overturn. At 4-3, they allowed Real Madrid two one-on-one chances in the dying stages, through Victor Munoz…

…and Kylian Mbappe.

Barcelona could have had more goals themselves, of course, with Raphinha uncharacteristically squandering some sublime crosses from Yamal. But this was typical 2024-25 Barcelona, the side that have launched extraordinary comebacks and have, when leading, taken extraordinary risks.

They’d previously won matches 5-4 against Benfica, 4-3 against Celta Vigo and 3-2 against Borussia Dortmund. Maybe the most telling match was the first leg of the Copa del Rey semi-final against Atletico Madrid, when they went 2-0 down, then came back to lead 4-2, but then collapsed late on and drew 4-4. Or maybe it was three weeks later, when they went to Atleti in the league, went 2-0 down and won 4-2. Or maybe it was their semi-final exit against Inter, when they drew 3-3 at home and then lost 4-3 away.

On Sunday, Mbappe became the fourth player this season to score a hat-trick against Barcelona but finish on the losing side. Compared to two seasons ago, the last time they won the league, Barcelona have scored 25 more goals, and conceded 16 more goals. And there are still three games left this season.

Of course, this is what Hansi Flick is all about. When his Bayern Munich won the Champions League in 2019-20, their defensive line was probably the most aggressive European football has seen (at least in the modern period when there are more liberal interpretations of ‘interfering with play’ compared to the 1970s, when catching anyone offside brought a stop to the game, even if they were nowhere near the ball). It was an 8-2 victory over Barcelona which demonstrated that approach most succinctly.

Hansi Flick’s tactics are extremely aggressive (Fran Santiago/Getty Images)

Flick has replicated that approach at Barcelona with a largely inexperienced backline, and even when Wojciech Szczesny, now 35, was tempted out of retirement as an emergency goalkeeper after Marc-Andre ter Stegen was injured. Szczesny was never the most mobile, even in his peak years, and Flick admits the Pole still enjoys the odd cigarette. His rash challenge on Mbappe on Sunday hinted at his tardiness, although overall he’s swept off his line effectively. It helps that Szczesny has always come across as not being too bothered if he makes a mistake, which is conducive to playing in a system where players will find themselves exposed and embarrassed from time to time.

Advertisement

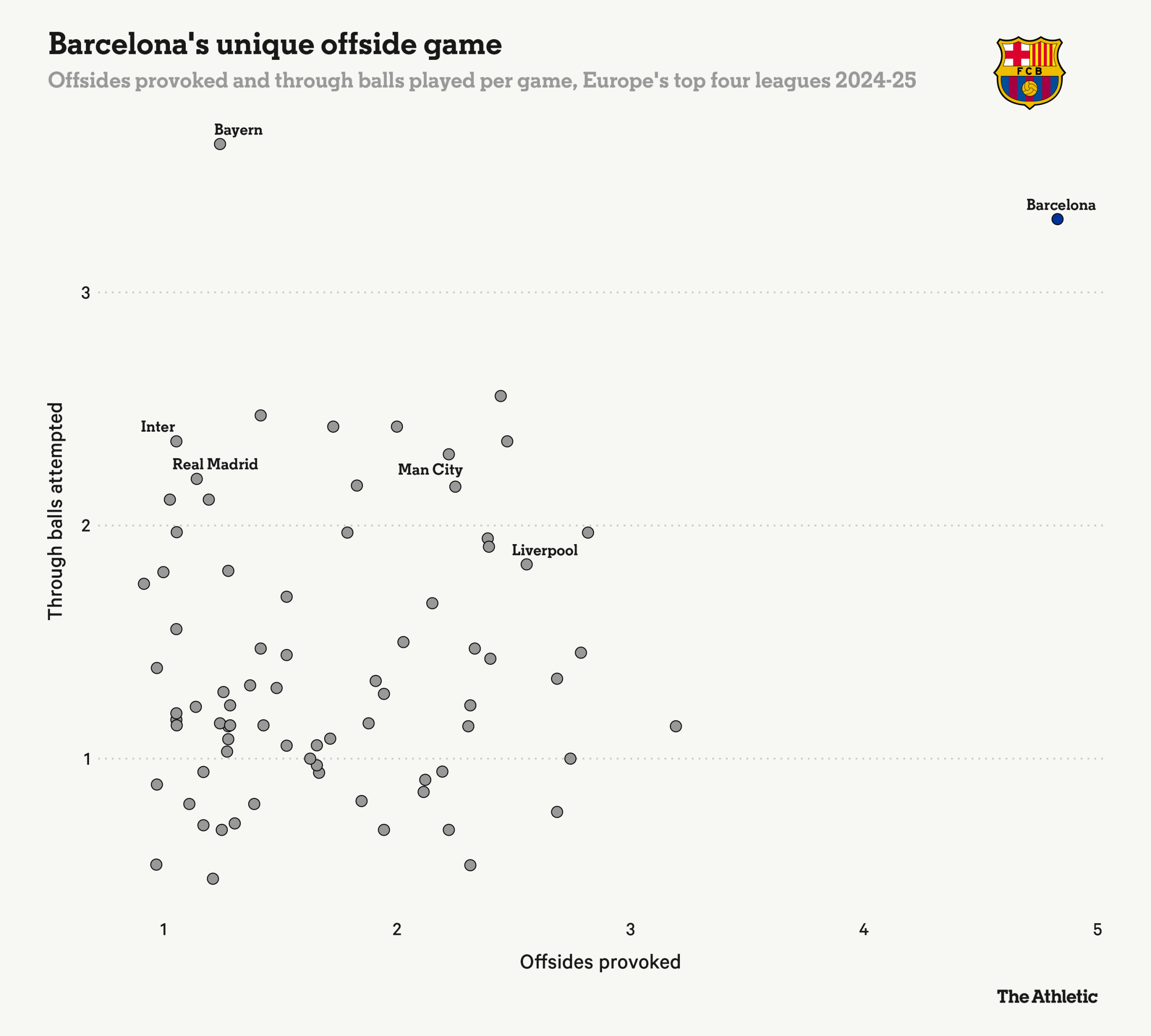

Flick’s calculation, like that of Johan Cruyff when manager in the early 1990s, is that the approach plays off overall. This graph shows that Barcelona are in a world of their own in terms of catching the opposition offside, and they and Bayern are also in a different league in terms of playing through-balls. In other words, Barcelona leave space in behind, and they exploit space in behind.

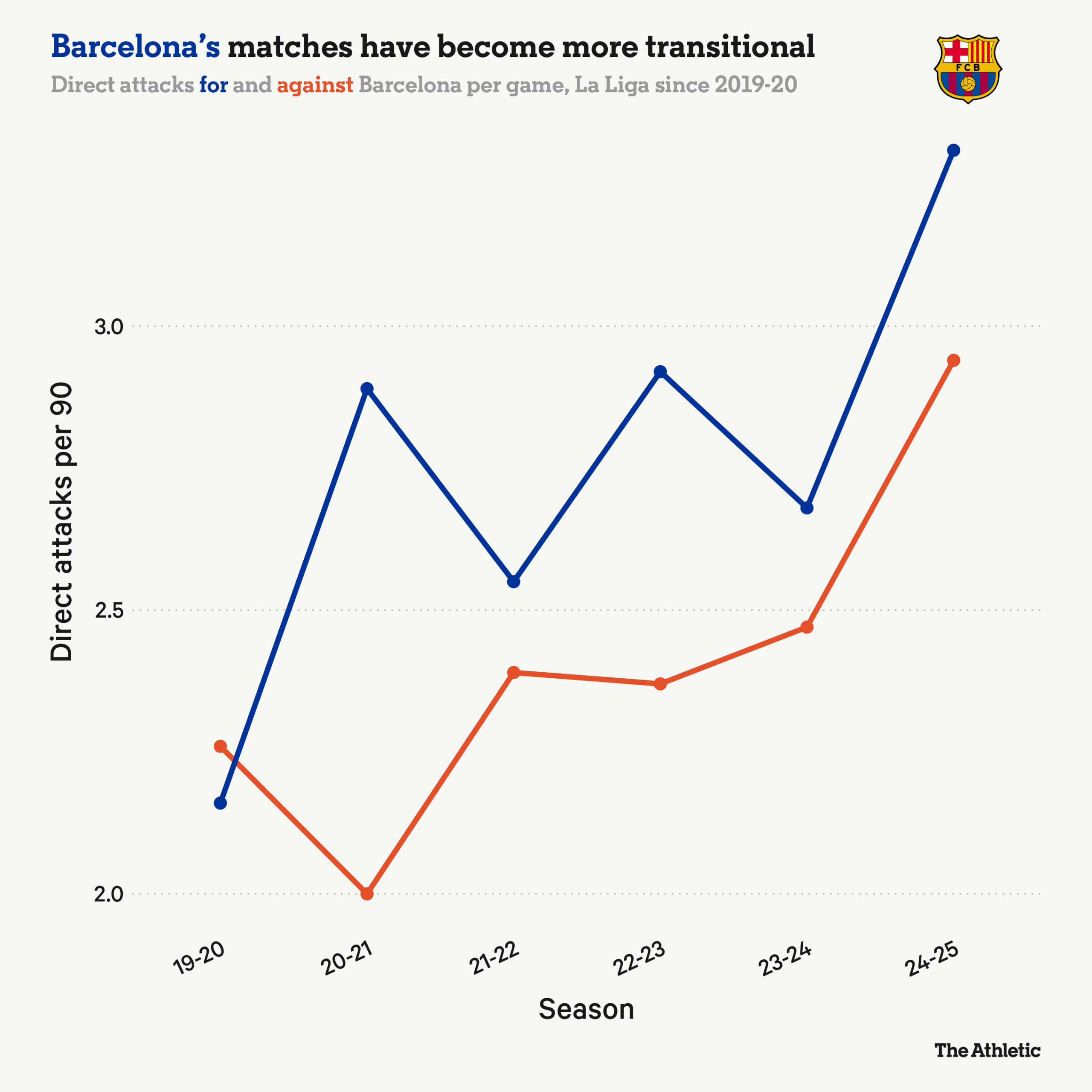

That demonstrates Flick has paired that aggressive defensive line with an aggressive attack. Barcelona have always been a front-foot side, but during their most recent period of consistent dominance, under Pep Guardiola, they interpreted this as a mission to dominate possession through long, drawn-out spells on the ball. Xavi Hernandez, the poster boy for that approach, often used to turn down the opportunity to release runners on the break, in order to let Barcelona organise their structure through possession play, and impose himself on the ball in the opposition half.

In contrast, this Barca side break in behind immediately. Raphinha has been a revelation, not merely playing as a flashy winger but by breaking in behind to become a consistent goalscorer, often taking advantage of Robert Lewandowski’s clever movement and subtle directing of passing and runs. Ferran Torres has provided runs in behind in recent weeks, with the likes of Yamal and Dani Olmo also bursting into the box, not always to reach precise, slide-rule passes, but longer, diagonal passes from deep. Lewandowski has also played the role of target man at times, encouraging Barcelona to cross the ball: sometimes simply taking a chance and hoofing it into the box.

Previous Barcelona regimes would scoff at this; there was a belief that the faster you attacked, the faster the ball would come back at you. Guardiola always wanted to avoid basketball-style games. But Flick embraces it.

The only question is whether, at times, Barcelona can, or need to, offer more control.

It does seem wrong, for example, that (even when accounting for them scoring 23 more), Barcelona have conceded one fewer goal this season than a desperately disorganised Real Madrid side, who have regressed towards their old obsession with star players rather than balance. On Sunday, as in most big games this season, Carlo Ancelotti’s side were a shapeless mess.

Advertisement

Indeed, both third-placed Atletico and fourth-placed Athletic Club have conceded fewer goals than Barca. In this respect, the issue hasn’t generally been the high line, which has largely worked beautifully. But there are periods when Barcelona could afford to be more cautious in possession, more reserved in terms of moving the ball forward quickly.

When leading Inter in the dying stages of that thrilling semi-final second leg, Barcelona tried to extend their lead and ended up losing it. Some might suggest that killing the game isn’t what Barcelona are all about. That’s true of this season, but not of past sides.

(Alex Caparros/Getty Images)

Things might change next year. This season, we’ve rarely seen Gavi in the side. To be frank, when he’s played Barca have been less exciting: in the 12 games Gavi has started, Barcelona have scored only once in seven of them. In another, against Sevilla, they scored once before half-time, then three after the break when Gavi was replaced by Fermin Lopez, who pushed on more.

It feels strange to cite fewer goals scored as a positive. But at times, maybe that’s what Barcelona need. Granted, they very nearly defeated Inter playing in this all-out-attack manner. But really, they shouldn’t have lost it: Inter weren’t close to their best, and Barcelona still allowed too many transitions. If you concede seven goals in a two-legged semi-final, you’re unlikely to progress. More tactical intelligence should come with experience; Barcelona’s starting XI this season has been the joint-youngest in La Liga, alongside Valencia.

More cautious possession might prove useful in the must-not-lose nature of European knockout matches, but the attack-minded approach this season has clearly suited the win-as-much-as-you-can nature of a league campaign. And they’ve done it in style — a style which has been more attack-minded than anyone else in Europe, and more attack-minded than even the most legendary Barcelona sides of the past.

(Header photo: Alex Caparros/Getty Images)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment