Crystal Palace fans will forever remember Dean Henderson for his contribution at Wembley on Saturday.

He had a small catalogue of excellent saves, none better than the thrust low to his right-hand side to stop Manchester City forward Omar Marmoush from equalising from the penalty spot. In the wake of their 1-0 FA Cup final win, the first trophy in the club’s 164-year history, Henderson has written his name into the fabric of the south London club with that performance. It would not be a surprise to see the club shop at Selhurst Park stock the blue cap he donned in the second half as a commemorative token to the 28-year-old’s heroics.

Advertisement

But it could all have been very different.

With the raucous Palace end still enjoying Eberechi Eze’s opening goal six minutes earlier, City defender Josko Gvardiol dropped a chipped pass in a dangerous spot between Henderson and the Palace defence.

References to the “corridor of uncertainty” are typically restricted to crosses flashed across the six-yard box from wide areas, but in the increasingly vertical modern game, lofted passes over high defensive lines require the goalkeeper to make high-risk decisions.

When it works, it nullifies an opponent’s direct threat. When it does not, it can gift goalscoring opportunities.

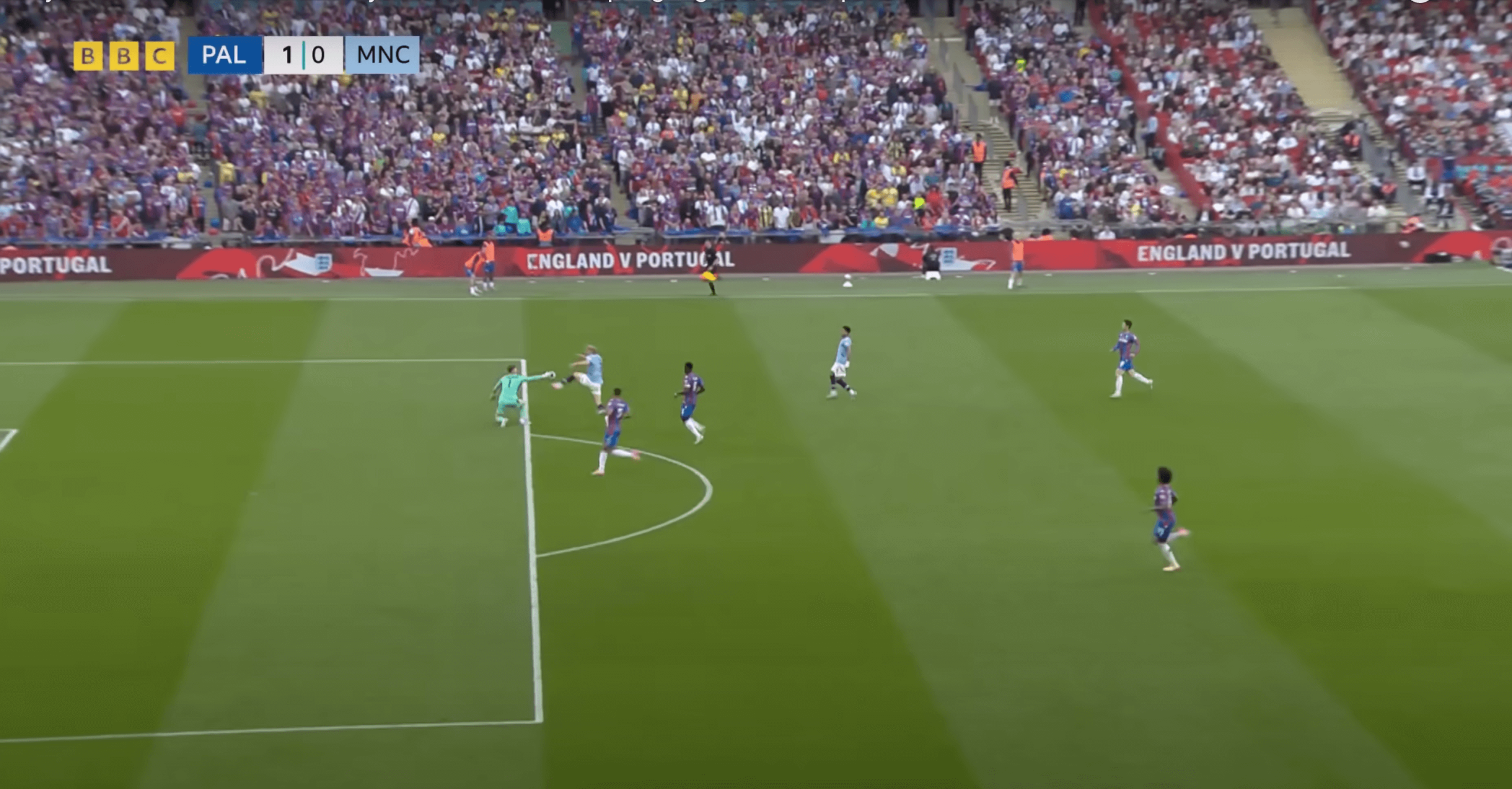

Erling Haaland raced ahead of Palace defenders Marc Guehi and Maxence Lacroix, with the ball approaching Henderson on the edge of the box.

The goalkeeper inched back and forth, calculating whether he could get there before the Norwegian.

“At Malmo, we have a principle with long balls over the top,” says Matt Pyzdrowski, an academy goalkeeper coach at Swedish side Malmo and goalkeeping analyst for The Athletic.

“We have a principle with long balls over the top. If the ‘keeper will 100 per cent be first to the ball outside the box, they can go out and sweep the situation. If the attacker will be first to the ball, the ‘keeper goes back and defends their goal. If the ball is coming into the box, which this almost is, then the ‘keeper has to intervene.

“In this situation, there are defenders close enough to Haaland’s back that Henderson doesn’t want to go out and sweep. I think part of the hesitancy in this situation is that they are so close. Originally, he thinks, ‘OK, I’m going to go out and sweep,’ but then it’s clear Haaland will be first to the ball.

“So then there’s a little bit of panic, and he thinks, ‘OK, I need to get back inside my box and defend the goal.’ But the ball keeps coming. And then there’s a moment where Henderson tries to intervene and does right outside the box with his hand.”

With his feet still inside the box, but his arm outstretched to meet the ball a couple of yards outside, Henderson took the ball from Haaland’s foot and palmed it away from goal and towards the touchline.

Marmoush had a clear view of the incident and didn’t throw his hands up and appeal for a penalty, nor did Haaland, who chased to retrieve the ball. Perhaps caught out by the directness of City’s play, the near-side assistant referee was behind the play and did not flag for a handball.

“It’s not crazy that the linesman didn’t call, because he was behind the play,” says Pyzdrowski. “It’s hard for him to see where Henderson’s hand is making the infraction. And then none of the City players react to it. I think if Marmoush puts his hands up and starts screaming and turning towards the referee, it could stress him into making a decision. I think the fact that nobody reacted shows how close it is.”

With the benefit of replays, it soon became evident that Henderson had met the ball outside the box with his hand.

VAR cannot retrospectively award fouls for handling outside the box, as it only has jurisdiction over penalties, goals, red cards and mistaken identity.

In this case, Jarred Gillett could only award a red card for denial of a clear goalscoring opportunity, but he judged the incident not to be worthy of that punishment as the direction Haaland was heading made a goalscoring opportunity possible, but not obvious. However, for many people watching, including former Manchester United and England forward Wayne Rooney, Henderson should have been sent off.

Advertisement

“It’s a red card, 100 per cent,” Rooney said on the BBC coverage at half-time. “Haaland’s about to knock it around him, and (Henderson) sweeps the ball away. How can we get this wrong?”

In Pyzdrowski’s view, Henderson could not have handled the situation much better, considering the position he found himself in. Had he flown forwards and punched the ball away from goal, taking himself outside the box, the officials’ decision would have been straightforward.

His intelligence in the moment to fall back and stay inside the box, obscuring his position at the time of contact, as well as pushing the ball wide in Haaland’s direction of travel, created an illusion regarding the strength of the Norwegian’s touch in real time, making the decision more complicated.

“If you could redo the situation, you’d tell Henderson to drop directly to his goal and hopefully the defenders would get there to put enough pressure on him,” says Pyzdrowski.

“If they don’t, that’s when you need to intervene and go out. It becomes a situation where they need to make a save, whether it’s a spread, block or wait-and-react situation. Hopefully work with the angle, because the ball is heading away from the goal, to push the striker outside and force him to the near post.

“But if there’s any credit to Henderson, I think he handles it well considering the circumstances and his hesitation. Whether it was conscious or not, getting himself back into the box and pushing it away from the goal was smart. If he doesn’t get a touch there, it is a much different situation.”

As teams from the top to the bottom of the Premier League operate a high line, reading those direct, long-ball situations has become a primary requirement for goalkeepers. Still, even for the elite shot-stoppers, the high-risk nature means coaches accept that even the best will occasionally slip up.

Advertisement

“This type of ball, where it’s over the top and relatively straight, is very hard,” says Pyzdrowski. “It’s easier to judge a ball coming in from the side because it’s a little easier to work with angles, but you don’t get that depth when it’s straight on. That’s where these types of balls create problems for goalkeepers.

“I don’t think it’s a surprise that more and more teams, even the big teams like City, are playing very direct. The old-school mentality was to play to the channels, and I think that’s going out now. It’s more central. Because teams play with high lines, and the space is in behind, these situations can happen.”

It’s a situation that will continue to cause controversy for City fans who feel hard done by, and perhaps a prompt for Henderson to skip when he inevitably watches this game back in the future. It’s a small mark on a historic final, but in ending one of football’s longest trophy droughts and booking their place in the Europa League next season, very few people of a Palace persuasion will mind.

(Top photo: BBC Sport)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment