Paul McVeigh is a former Premier League footballer turned performance psychologist who has used visualisation to help take him to the top of both professions. But he still believes the mental side of the game is overlooked by far too many.

“I would say that while there might be more awareness now, I do not think there is more interest,” McVeigh tells Sky Sports. “Very few players actually do it. Very few of them actually ever really buy into the benefit of the psychology of mental performance.

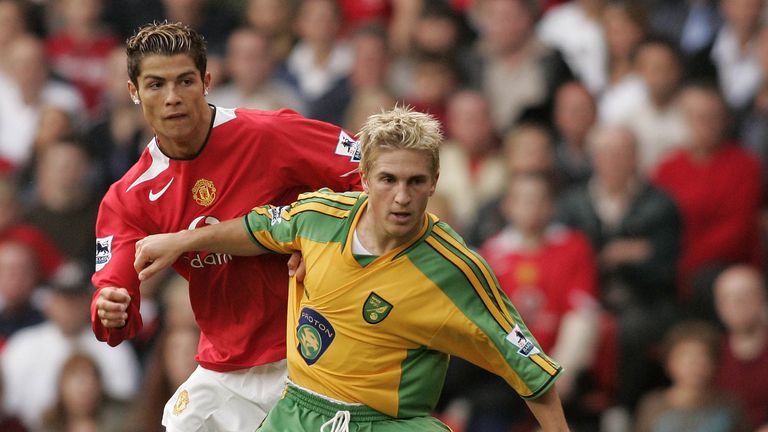

One might assume that in a multi-billion-pound industry such as football, every edge is being explored. But McVeigh, a Northern Ireland international who played and scored in the Premier League for Tottenham Hotspur and Norwich City, says that is not the case.

“How many players are consciously improving the mental side of their game? Very few in my experience.”

And that experience is vast. Following retirement, he spent years presenting to players inside clubs, invited to discuss the importance of psychology on their performance. Many players had no interest whatsoever. “They were just ticking a box,” he explains.

“Those seven years doing that were really difficult because you were almost having to sell the subject of sports psychology to elite athletes, which is crazy. With some, you could literally give them the winning lottery numbers and they would not be interested.”

Others did embrace it. “There were always four or five who loved it. They wanted to learn and improve.” McVeigh mentions Jacob Murphy, Aaron Wan-Bissaka and Tyrick Mitchell, all now performing in the Premier League, as examples of those who took it on board.

McVeigh realised earlier than most that having his head in the right space was impactful. He recalls a conversation with his golf-obsessed father when he was just 17 that opened his eyes to the powers of visualisation. “I phoned home,” he explains.

“My dad was a big golf fan and he told me that Jack Nicklaus would always visualise where he wanted the shots to go. He actually sent me a tape to learn this process of visualisation, getting myself into what is now known as the zone, or a flow state.

“I was just open to it. I started doing it when I was a kid, visualising the goals that I wanted to score every morning and every night. The majority of the goals that I did score in my 20-year career were exactly as I visualised as a kid. I massively benefited from it.”

But what is this visualisation? Everyone has imagined scoring the winning goal in the World Cup final, surely? Well, sort of. But McVeigh breaks it down in much more detail. “It is essentially about creating a movie in your mind that you want to happen,” he says.

“For example, visualise picking the ball up somewhere between the centre circle and the edge of the 18-yard box. Then, visualise pulling off to the side to receive the ball, dribbling past someone and shooting into the top corner from 25 yards out.

“Now, just keep playing it over and over. But add more detail to it. Think about the colours around you, the body shape of the opposition, whether they are big or small, the noise of the crowd, whatever it takes to make the whole scenario real in your own mind.”

The goal is to make all this feel automatic. “You are just trying to create a neural pathway with the aim of becoming unconsciously competent.” This is the final stage of competence, when a person is able to perform a task without needing to think about it.

McVeigh offers the example of what happens when a player runs through on goal in a one-on-one situation. “You often hear commentators say that the player had too much time. It is because that neural pathway is not ingrained. They are thinking about it.”

It is the mind not the body, mentality rather than technique, that is often the key factor. McVeigh mentions Cole Palmer, who scored 28 goals in his first 37 Premier League games for Chelsea before embarking on a run of 18 appearances without scoring.

“One of the best players suddenly goes three months without scoring? It is all down to state of mind.” How about Mohamed Salah? “He is not thinking whether he will score going into games, he is thinking how many. That is a real differential in mindset.”

He talks of remembering the need to control the controllables, focusing on the things that you can change as a player – which is your own performance rather than those around you. “You cannot even control your team-mate and they are trying to help you.”

McVeigh continues: “I really do think this is where players struggle when they do not have the strategies in place. When they do not have the experience of dealing with themselves and putting themselves in the pressure situations it can be really difficult.

“The players who learn fastest and continue to learn are the ones who keep going.” Two former team-mates standout. “People like Teddy Sheringham. People like Sol Campbell who moved to centre-half and just kept learning to be a better and better centre-half.”

McVeigh is keen not to romanticise the past too much because he has watched the games back. “It is embarrassing actually. I would love to have some sort of defence for my entire generation but I have seen too much footage. The ball is like a hot potato.”

He laughs at “players who are in 20 yards of space and just launch it” and remembers going up against Spain for Northern Ireland. “Carles Puyol or whoever would just chest it down, give it to Xavi and we would not see the ball again for 10 minutes.”

He disagrees with Sky Sports pundit Gary Neville’s assertion that the modern game is more boring because players are like robots now. “You cannot be a robot because the game changes every split second and you are constantly reacting to the game,” he says.

“So, I completely disagree on the reduced freedom part. Where I agree with him is on the amount of information that they get. Now, you might have nine different coaches who all want to tell the player something. I do not necessarily think that is helpful.

“Arsene Wenger used to give that Arsenal team three points before a game. Psychology research tells us that the maximum amount of information that we can cope with is seven bits of information. Wenger wanted to reduce it down to three things.”

A clear mind helps, preferable one that is free from negative thoughts. McVeigh still remembers being, in the prime of his career at Norwich and a sports psychologist pointing out that all of the information they were being given was framed negatively.

“Everything that we were talking about, the language being used, was all about what we did not want to do. You might think this is not a huge deal, it is only language. But psychologically, you do not focus on the don’t part – that is focusing on the negative.”

Now 47, McVeigh’s career has evolved from talking to football players to speaking to figures from across sport and the business world. He is leaning on those same learnings, first taught to him by his father as a teenager – with help from Jack Nicklaus.

“I had never spoken publicly before but I need to do it all the time in the work that I do now. So I started visualising stepping onto these stages for Microsoft and Rolls-Royce and KPMG.” He is fresh from speaking at the Women in Sport conference in London.

He still works with players, but only those who want to improve. “We do not deliver group sessions now.” Those willing to embrace it will be the ones who find an edge. Because McVeigh is more convinced than ever. “It all comes down to psychology.”

Sky Sports to show 215 live PL games in 2025/26

From next season, Sky Sports’ Premier League coverage will increase from 128 matches to at least 215 games exclusively live.

And 80 per cent of all televised Premier League games next season are on Sky Sports.

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment