In March 2013, Borussia Dortmund’s sporting director, Michael Zorc, answered his phone.

Dortmund had won a Bundesliga and DFB Pokal double the season before. Now, Jurgen Klopp’s team were powering through the Champions League. They had beaten Manchester City and Real Madrid at the Westfalenstadion in the group stage, had just eliminated Shakhtar Donetsk to qualify for the quarter-final, and were the darlings of neutrals all over Europe.

Advertisement

But when Zorc answered his call, there was Volker Struth, Mario Gotze’s agent, on the other end of the line.

Gotze and his family had moved to Dortmund when he was five. At 11, he joined BVB’s academy, developing to become one of the biggest talents the club had seen and the great hope of German football.

And Struth was ringing to tell Zorc that Bayern Munich intended to activate Gotze’s release clause and there was nothing anybody at Dortmund could do about it. By Struth’s recollection — recounted in his autobiography, My Moves — a shocked Zorc asked to call him back a few minutes later. When he did, he unleashed a volley of anger.

Bayern pursued Gotze as a compromise. Pep Guardiola was to be appointed head coach in the summer of 2013 and his two initial requests were for the club to sign Thiago Alcantara, which they did, and Neymar, which they did not. Bayern baulked at the cost of the Brazilian and worried about how he might adapt to Germany.

They suggested Gotze instead.

Gotze was born in Bavaria and grew up a Bayern fan. Combined with the opportunity to play for Guardiola, it was an opportunity he felt unable to turn down.

Days after Struth’s phone call, he and Gotze met Klopp and Zorc in a downtown pizza restaurant, which had been closed to accommodate them. Dortmund were riding the crest of a wave, they explained. Gotze was central to everything they still felt they could achieve.

It made no difference — and to onlookers, it was a familiar story.

The Dortmund team, with Gotze (second from left, front row) at its core, in 2013 (John MacDougall/AFP via Getty Images)

For decades, Bayern had been surrounded by the suspicion that their transfer policy was aimed at weakening Bundesliga opponents as much as strengthening their own squad. Given Gotze’s importance to Dortmund and Bayern’s lack of need for a player of his profile, this was seized upon as further evidence and added to a list of grievances that was, by that stage, more than 30 years long.

Advertisement

In his book about the club’s history, Bayern: Creating a Global Superclub, Uli Hesse recalls the signing of Karl Del’Haye from Borussia Monchengladbach in 1980 as the first instance in which that accusation was made.

Gladbach were Bayern’s nearest rivals during the 1970s and while they had fallen back by the end of the decade, winger Del’Haye had been part of the BMG side that won back-to-back-to-back Bundesliga titles between 1975 and 1977.

In the years following, Bayern unquestionably dominated the German market and continuously took important players from their rivals. A non-exhaustive list from the 1980s and 1990s includes Lothar Matthaus, Andreas Brehme, Olaf Thon, Stefan Reuter, Jurgen Kohler, Stefan Effenberg, Thomas Helmer, Mehmet Scholl, Oliver Kahn, Andreas Herzog, Mario Basler and Giovane Elber.

In the 2000s, they took Michael Ballack, Lucio and Ze Roberto from the Bayer Leverkusen side that reached the Champions League final. Lukas Podolski was signed from Koln, Miroslav Klose from Werder Bremen, and Mario Gomez from Stuttgart. Manuel Neuer and Leon Goretzka transferred from Schalke, Mario Mandzukic from Wolfsburg, and — of course — Gotze, Mats Hummels and Robert Lewandowski were snatched away from Dortmund.

That is only a select list, meaning the assumption that Bayern will buy up their competition — or buy to prevent a team from becoming their competition — tends never to be too far away.

Ballack (left) celebrates Bayer Leverkusen’s Champions League progress beyond Liverpool in April 2002 (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

In April 2024, when Bayer Leverkusen won their first Bundesliga title, 11Freunde, the German football magazine, ran a feature that claimed to have discovered a 17-player list that constituted “Bayern’s secret transfer plans” for the summer.

It was a carousel and as each image passed, it was revealed to be 16 Leverkusen players and head coach Xabi Alonso, with Thomas Tuchel — then Bayern coach — set to be “demoted to water carrier” at Allianz Arena.

Advertisement

It was a joke, of course, but Bayern did then spend at least part of last summer trying to find an agreement with Leverkusen for Jonathan Tah, their German international centre-back, and have long been linked with Florian Wirtz, the brilliant Leverkusen playmaker.

The Wirtz saga is natural. While rival supporters may roll their eyes, the 21-year-old is one of the best German players of his generation. If Bayern were not pursuing him, that would probably be harder to explain.

But the issue is complicated.

Bayern’s strategy over the years needs to be viewed through the specific prism of German football.

They are alone at the top of their domestic league, in both a financial and footballing sense, making them the only “destination club” in the country. For German or German-based players who do not want to play abroad, they are uniquely positioned.

But they do not necessarily behave in a uniquely predatory way, as a comparison with English football illustrates.

When a player within the Premier League feels he has outgrown a mid-level club, there are all sorts of avenues available. Whether he is pursuing silverware, wealth or the opportunity to play in the Champions League, there are four, five or perhaps now as many as six or seven clubs offering that kind of stage.

Anthony Gordon was able to leave Everton for Newcastle. Jack Grealish left Aston Villa for Manchester City. Declan Rice moved from east to north London, swapping West Ham for Arsenal.

Under Bundesliga conditions, all three would have joined Bayern. So, it’s not necessarily that a different dynamic is at work in Germany and being exploited by Bayern; more that — unlike in England — there is only one Bayern, rather than five or six.

Still, they can be provocative from that position, stoking the perception of an intent to be disruptive. The Wirtz situation has, on several occasions, been an example of that.

Advertisement

Speaking in late February, former Bayern CEO Karl-Heinz Rummenigge told newspaper Abendzeitung that he was making no secret of “the fact that it must clearly be our goal to sign Wirtz” and that “everyone at FC Bayern agrees that he is exactly the player we want to sign. Not to weaken Leverkusen, but to strengthen us”.

Alonso speaks with Wirtz (Oliver Hardt/Getty Images)

Rummenigge was speaking after Uli Hoeness, the club’s honorary president, had already described signing Wirtz as a “dream” in an interview with Kicker.

The timing could hardly be ignored. Rummenigge commented the week before Bayern were due to face Wirtz’s Leverkusen in the Champions League. He was a hot topic for journalists ahead of that game and so it was natural for Bayern officials to be asked, but both could plausibly have batted the questions away.

Skulduggery was suspected — including by Simon Rolfes, Leverkusen’s CEO for sport, who perceived it as a deliberate ploy and one he had seen before.

“It doesn’t interest me at all,” Rolfes responded when asked about Rummenigge’s comments in a press conference, “and it doesn’t affect us. Bayern were doing this before big games when I was reading Kicker as a 10-year-old. So, in that sense, it’s maybe not a new tactic.”

Back then, Bayern’s pursuit of domestic players had a different context. In the 1980s, the Bundesliga was unable to compete with the wealth of Italian football. To highlight that disparity, in the same month Bayern broke the German transfer record, paying €3million (£2.6m; $3.3m) for Brian Laudrup from Uerdingen, Roberto Baggio joined Juventus for €12m from Fiorentina.

German football’s true professional era did not begin — openly, at least — until the Bundesliga began in 1963. Before that, the best players in the league had always been prey to foreign sides from fully professionalised leagues. Even by the late 1980s and 1990s, that talent drain was still in effect, with Bayern losing Rummenigge, Matthaus and Brehme to Inter, Kohler and Reuter to Juventus, and Laudrup and Effenberg to Fiorentina, all for big wages, often for big fees.

Advertisement

German football’s commercial era did not properly begin until 1998 and the legislation — today known as the 50+1 rule — that allowed clubs to run their football departments as public limited companies. By then, a different power had emerged.

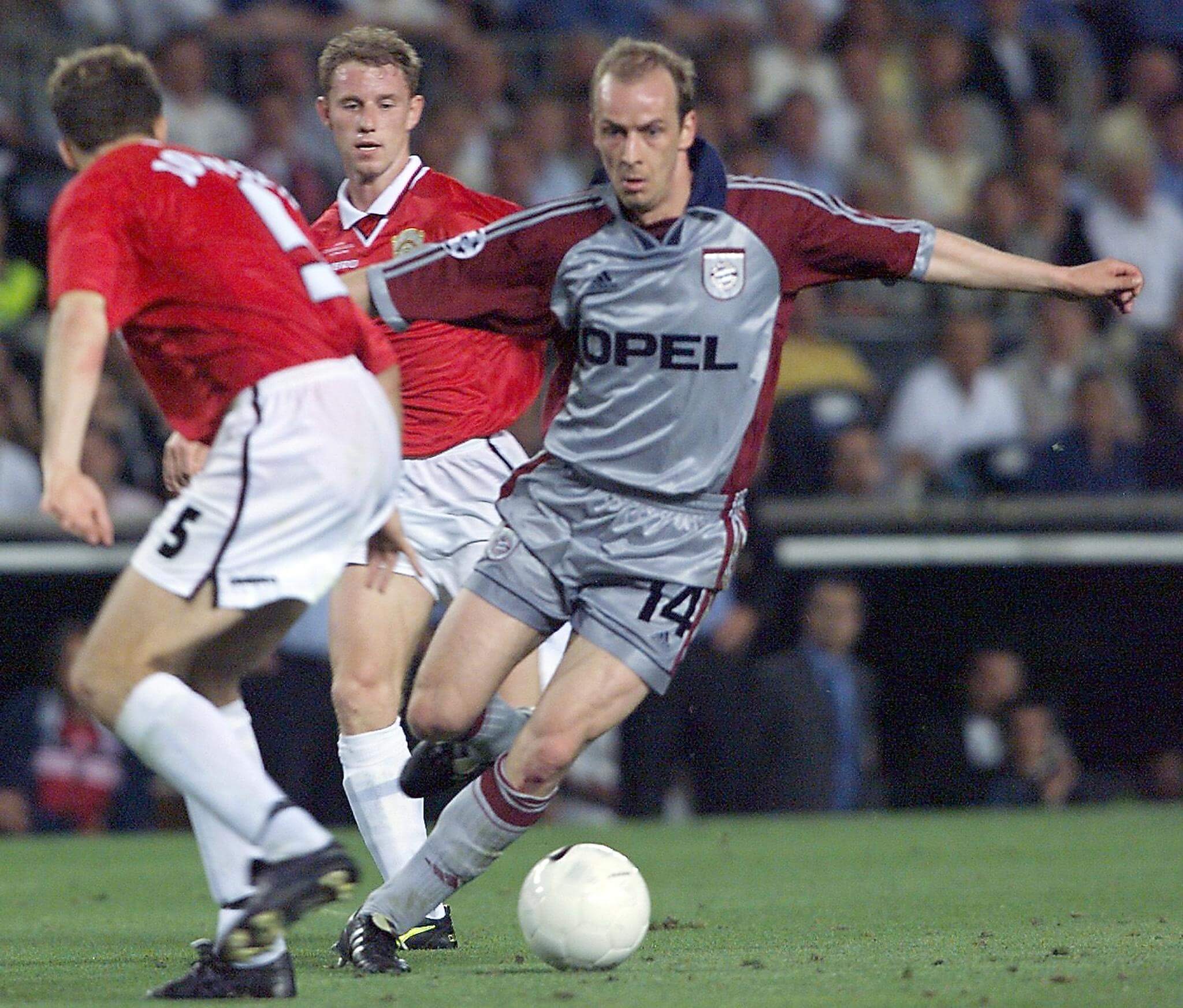

In the summer of 1996, Mario Basler became the most expensive signing in their history, joining from Werder Bremen for €4.1m. A few weeks later, Newcastle United paid €18m for Alan Shearer.

Basler attempts to dribble past Manchester United’s Ronny Johnsen in the 1999 Champions League final (Patrick Hertzog/AFP via Getty Images)

For a long time, Bayern were only able to shop in certain parts of the global market. It’s logical, then, that they tried to dominate their own.

Until 1996, the club was also restricted by what was known as the “three foreigner rule”, which meant clubs competing in UEFA competitions could only field three foreign players in matchday squads. Naturally, this compelled clubs with continental ambitions in Germany and beyond to first look inwards, towards the finest domestic talent available.

If that had the consequence of also weakening aspirant opponents then, from Bayern’s perspective, all the better.

Interestingly, those trends are not quite the same today.

The three-

The three foreigner rule is long gone, of course, and Bayern are now a financial powerhouse, meaning they can buy from almost any club in Europe. Since 2020, the arrival of Marcel Sabitzer and Dayot Upamecano from RB Leipzig are really the only signings that could be described as being from a direct rival.

Before that, the €35m spent on Benjamin Pavard from relegated Stuttgart in 2019, the combined €33m on Niklas Sule, Sebastian Rudy (in 2017) and Sandro Wagner (in 2018) from Hoffenheim, and the €8m on Werder Bremen’s Serge Gnabry (2017) are the only deals of note. In fact, not since signing Mats Hummels from Dortmund in 2016 has Bayern truly completed one of those deals — equal parts beneficial to them and wounding to a rival.

Advertisement

In a different era, Jude Bellingham, Jadon Sancho and Erling Haaland might have left the Westfalenstadion for Allianz Arena. Kai Havertz could have headed south from Leverkusen, and Josko Gvardiol, Dominik Szoboszlai and Dani Olmo might have signed from Leipzig. As it was, they all left Germany and signed for clubs abroad.

It goes back further. When it became clear that Mesut Ozil would leave Werder Bremen in 2010, Bayern were interested in signing him. He chose Real Madrid. As did Stuttgart’s Sami Khedira.

Ozil and Khedira chose Real Madrid over Bayern (Shaun Botterill/Getty Images)

Each individual case was different, variously borne of the financial strength of the Premier League, the allure of Madrid and London and, in a few cases, the unsuitability of the player in question.

The broader point, however, might be to note the many options now available to those wishing to ascend in the game and how, given its reputation for developing adaptable talent — with speed, technique and the ability to play effectively in transition — the Bundesliga has become football’s global shopping mall and no longer the preserve of its biggest club.

Bayern are no longer the natural choice for someone like Wirtz. With a nine-figure asking price, it is not even clear whether they could afford him.

But if they can and if he does find his way to Munich one day, then expect this conversation — this generational argument — to rumble on.

(Top photo: Alex Grimm/Getty Images)

This news was originally published on this post .

Be the first to leave a comment